Pierre Le Gros, The Triumph of Religion over Heresy, the transept of the Church of Il Gesù

The Triumph of Religion over Heresy, Pierre Le Gros, Church of Il Gesù

Altar of Ignatius of Loyola (Cappella Sant'Ignazio), transept of the church of Il Gesù

Pierre Le Gros, statue of St. Ignatius, Cappella Sant'Ignazio, Il Gesù church

Sarcophagus of Pope Pius V, Pierre Le Gros, Basilica of Santa Maria Maggiore

Pierre Le Gros, altar of St. Luigi Gonzaga, transept of the Church of Sant'Ignazio

Pierre Le Gros, State of St. Francis Xavier (Francesco Saverio), Church of Sant’Apollinare

Pierre Le Gros, The Arts Paying Homage to Pope Clement XI - terra-cotta relief, Accademia di San Luca, pic. Wikipedia

Pierre Le Gros, The Death of St. Stanislaus Kostka, the Jesuit convent at the Church of Sant’Andrea al Quirinale

Pierre Le Gros, The Statue of St. Dominic, Basilica of San Pietro in Vaticano, pic Wikipedia

Pierre Le Gros, The funerary monument of Pope Gregory XV and Cardinal Ludovico Ludovisi, Church of Sant’Ignazio

Pierre Le Gros, Tobit Lending Money to Gabael and Théodon, a relief in the Monte di Pietà Chapel in the Palazzo del Monte di Pietà

Pierre Le Gros, The funerary monument of Cardinal Girolamo Casanate, Basilica of San Giovanni in Laterano

Pierre Le Gros, statue of Cardinal Girolamo Casanate, Biblioteca Casanatense

Pierre Le Gros, statue of Cardinal Girolamo Casanate, Biblioteca Casanatense

Pierre Le Gros, statue of St. Philip Neri and the sculpting decorations in the Antamori Chapel, Church of San Girolamo della Carità

Pierre Le Gros, the altar devoted to St. Francis di Paola, Church of San Giacomo in Augusta

Pierre Le Gros, statue of St. Thomas, Basilica of San Giovanni in Laterano

Pierre Le Gros, statue of St. Bartholomew, Basilica of San Giovanni in Laterano

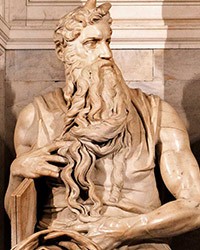

After the death of Gian Lorenzo Bernini, there came the time of monumentalism in the spirit of Classicism among Roman sculptors. The art of Le Gros was at the other end of this phenomenon. The statues which he completed with unimaginable virtuosity, eccentric in their form, seemed to be living their own life full of convulsions. They were the last breath of a grand style, which we usually refer to as late Baroque.

After the death of Gian Lorenzo Bernini, there came the time of monumentalism in the spirit of Classicism among Roman sculptors. The art of Le Gros was at the other end of this phenomenon. The statues which he completed with unimaginable virtuosity, eccentric in their form, seemed to be living their own life full of convulsions. They were the last breath of a grand style, which we usually refer to as late Baroque.

For two decades the French-born artist was the crème of the crop, he forced his style upon others, while numerous clients patiently waited for his works. We may pose the question of whether truly there were no other sculptors in the city on the Tiber – filled with the students and continuators of the great Bernini. Of course, there were, but he was the one who expertly combined the sculpting craftsmanship with the dramatism of vision, which exceptionally showed the spirit of the times of heightened struggles against the Reformation, heresy, and paganism – the enemies of the Roman Catholic Church.

The sculptor’s father (Pierre Le Gros the Elder) was active at the French court of Louis XIV and he was the one who introduced his son to the sculpting profession. Two uncles of the young artist were also sculptors. His Roman adventure began with a scholarship, which he (known as Le Gros the Younger) received from the French king as a token of recognition of his exceptional skills. Already in France, the youth had received several awards for his achievements in the fields of sculpture and drawing. He came to Rome at the age of twenty-four and continued his studies in the Roman French Academy, which was tasked with educating artists for the Bourbon monarchy and familiarizing them with the most important works of Roman art, both contemporary and ancient. In opposition to the guidelines of the French Academy, in 1695 the young Frenchman took part in a sculpting competition organized by the Jesuits for a sculpting group that was to adorn the altar of the patron of the Society of Jesus – Ignatius of Loyola in the Church of Il Gesù. The unknown young artist surprisingly intrigued by his dynamism and unbridled impetus of his vision, as well as the strength of showing evil and sin, which he displayed in the sculpting group The Triumph of Religion Over Heresy. From that moment the Jesuits, Dominicans, the pope, and private clients showered commissions upon him. Le Gros bid farewell to the French Academy and moved to his new home in the Palazzo Farnese. Rome, at that time enveloped by a true architectural and sculpting fever (prior to the planned Jubilee Year of 1700) became his second home, until his death. It is there that he created single, free-standing figures, fashionable at that time reliefs constituting altar reredoses, as well as elaborate sculpting compositions such as the imposing funerary monument of Pope Gregory XV. Until 1713 he was particularly admired by the Jesuits and it is for their newly created churches that Le Gros completed most of his works. He gained particular renown for the lying on a low bed polychrome figure of St. Stanislaus Kostka – a sculpture created for the novitiate of the Jesuit convent in the cell of the prematurely deceased saint near the Church of Sant’Andrea al Quirinale.

In 1700 Le Gros was admitted to the Roman Academy of St. Luke (Accademia di San Luca), he got married and felt right at home in the multi-cultural artistic community of the Eternal City, surrounding himself with both Italian and international artists, however, also not cutting himself off from his French connections and clients. After the untimely death of his first wife in 1704 Le Gros married the daughter of the then-head of the French Academy, Marie-Charlotte Houasse.

The artist also attracted the attention of the papal court, and especially the art-oriented Pope Clement XI, who had wanted to adorn the restored interior of the Basilica of St. John on the Lateran with figures of the twelve apostles. In 1702 a group of artists was entrusted with works on individual monumental statues. They were created according to a uniform concept developed by the pope's favorite – the painter Carlo Maratti. Only Le Gros was free to do as he chose. He could complete the sculptures (of saints Bartholomew and Thomas) in accordance with his own vision, nevertheless, he had to adapt his style to the artistic creations of other sculptors, which is why the sculptures do not stand out in any particular way. It is at that time that Le Gros began competing with the most ambitious Roman artist of those times – Camillo Rusconi. They competed with each other when it came to style and the number of commissions received but above all, each of them strove to have the leading role in Rome, while the local artistic community followed their every move.

The Roman Dominicans also held Le Gros in the highest regard. It is for them that he created several sculptures commemorating both their patron St. Dominic as well as other figures connected with the order.

The style of Le Gros was a mixture of that, which he learned from his father and uncles, with that which he picked up in Rome – and this does not simply pertain to the great Bernini, but also slightly lesser artists such as Domenico Guidi or Melchiorre Caffà. Another artist who influenced the sculptor was Baciccio – a great painter and fresco artist, whose principal work was the illusionist fresco in the dome of the Church of Il Gesù. Similarly to Baciccio, Le Gros's style was thoroughly dynamic, full of unbridled expression. In their elaborate visions, both artists no so much concentrated on one main part of the composition but applied a great number of various details, equilibristic perspective foreshortenings, and a veritable fury of draped robes of their figures. All this resulted in the works of Le Gros attracting the attention of viewers even from afar, but they also amazed those who looked upon the perfectly developed details from up close. These sculptures were so veristic it seemed that the artist had brought alive the marble or perhaps it was the marble that transformed into live beings.

A further testimony to the outstanding skills of Le Gros is, the completed jointly with the architect Filippo Juvarra, Antamori Chapel in the Church of San Girolamo della Carità. The central figure of this thoroughly original sculpting and architectural work shows Philip of Neri. He is floating with a window in the background, through which a warm, yellow light seeps in, somewhat dematerializing the figure of the saint.

The year 1713 brought about the beginning of misfortunes for the ambitious artist. It is then that his conflict with the Jesuits began – officially over the aforementioned statue of Stanislaus Kostka. The overly sure of himself artist had wanted to place his sculpture in the Chapel of St. Stanislaus in the Church of Sant'Andrea al Quirinale, however, the Jesuits did not agree to such a proposal desiring to leave the statue in the saint's cell. As a consequence, the relations between the artist and the Society of Jesus worsened. The French king decided against financing yet another statue of a disciple in the Lateran Basilica, which was to be completed by Le Gros, and thus the commission was suspended. In 1715 the artist’s father died while he himself fell ill with cholelithiasis. In order to settle matters pertaining to his inheritance and undergo surgery he departed for Paris. Sensing growing problems in the Roman artistic community he searched for contracts and commissions at the French court, however, the disfavor of local artists and members of the French Academy resulted in Le Gros returning to Rome in 1716 where he experienced yet another affront. The statue of the disciple which was promised to him was entrusted to Rusconi, who as the creator of four Lateran statues, which were all of high artistic value, was at the height of his career, gaining dominance in the sculpting community of Rome. Another blow fell upon Le Gros from the heads of the Academy of St. Luke, who made the decision to also tax artists who were not connected with this institution. Until then they were part of the free market and did not have to pay any taxes. Le Gros spoke out against this policy, which resulted in his exclusion from the Academy, and thus lack of access to public commissions, which ensured profits for artists connected with this institution. This was virtually the end of the sculptor’s activity in the Eternal City. From now on he had to look for work outside its borders. Most likely he was also devastated to learn that his rival Rusconi had been included among the ranks of the nobility, which was to be an evidence of the pope’s recognition of the artist and bestowing upon him the title of Cavaliere (knight). It is of course a title that Le Gros had wanted for himself. Several months later the artist died. He was buried in the church of the French commune in Rome – San Luigi dei Francesi. Six years later the new authorities of the Accademia di San Lucca vindicated him and posthumously restored his membership in the institution.

Works completed by Le Gros in Rome:

- The group The Triumph of Religion Over Heresy (1698), a silver figure of St. Ignatius of Loyola (1699) – the transept of the Church of Il Gesù

- The sarcophagus of Pope Pius V (1698) – the Sistine Chapel in the Basilica of Santa Maria Maggiore

- Altar of St. Aloysius de Gonzaga (1699) – Church of Sant’Ignazio

- State of St. Francis Xavier (Francesco Saverio) (1702) – Church of Sant’Apollinare

- Terra-cotta relief The Arts Paying Homage to Pope Clement XI (1702) – Accademia di San Luca

- The Death of St. Stanislaus Kostka (1703) – the Jesuit convent at the Church of Sant’Andrea al Quirinale

- The Statue of St. Dominic (1706) – Basilica of San Pietro in Vaticano

- The funerary monument of Pope Gregory XV and Cardinal Ludovico Ludovisi (1714) – Church of Sant’Ignazio

- Tobit Lending Money to Gabael and Théodon (1705) – a relief in the Monte di Pietà Chapel in the Palazzo del Monte di Pietà

- The funerary monument of Cardinal Girolamo Casanate (1708) – Basilica of San Giovanni in Laterano

- Statue of Cardinal Girolamo Casanate (1708) – Biblioteca Casanatense

- The funerary monument of Cardinal Cinzio Aldobrandini (1707) – Basilica of San Pietro in Vincoli

- Statue of St. Philip Neri and the sculpting decorations in the Antamori Chapel (1710) – Church of San Girolamo della Carità

- Statues of St. Thomas (1711) and St. Bartholomew (1712) – Basilica of San Giovanni in Laterano

- Design of the chapel and altar devoted to St. Francis di Paola (1714) – Church of San Giacomo in Augusta