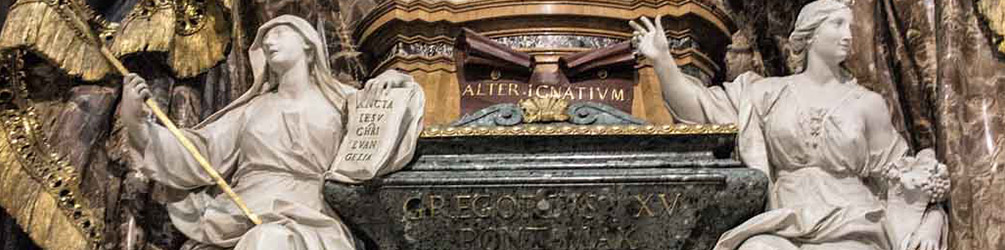

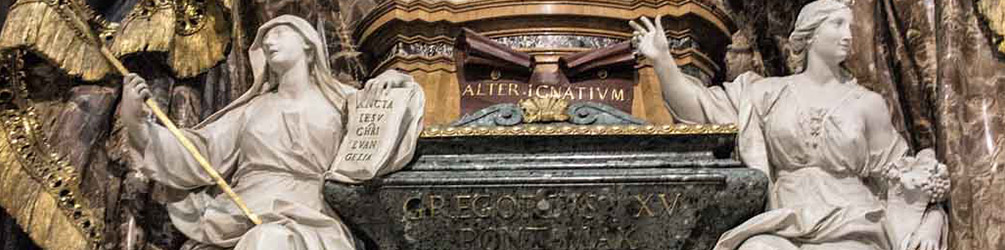

Pierre Le Gros, funerary monument of Pope Gregory XV and his nepot Ludovico Ludovisi, Church of Sant'Ignazio - Ludovisi Chapel

Allegory of Justice (Giustizia), Camillo Rusconi, Ludovisi Chapel, Church of Sant'Ignazio

Allegory of Prudence (Prudenza), Camillo Rusconi, Ludovisi Chapel, Church of Sant'Ignazio

Medallion with the image of Cardinal Ludovico Ludovisi from the tombstone of Pope Gregory XV, Church of Sant'Ignazio

Pierre Le Gros, statue of Pope Gregory XV, fragment of the tomb of the pope and his nepot Ludovico Ludovisi, Church of Sant'Ignazio

Pierre Le Gros, tomb of Pope Gregory XV and Cardinal Ludovico Ludovisi, Church of Sant'Ignazio - Ludovisi Chapel

The majesty, grandeur, and splendor of the monument of the posthumous glory of Gregory XV cannot be expressed in words. And it would be impossible to find another similarly triumphant monument even in the papal necropolis, meaning the Basilica of San Pietro in Vaticano. It is also hard to believe that, it immortalizes the pope who had not distinguished himself in any special way, one who held power in the Vatican for merely twenty-eight months. However, the monument was to not so much immortalize him but more importantly serve another much more pragmatic purpose – a propaganda and advertising one. Indirectly, it reflected not so much the power of the deceased pope, but of someone who was afraid to lose his power.

The majesty, grandeur, and splendor of the monument of the posthumous glory of Gregory XV cannot be expressed in words. And it would be impossible to find another similarly triumphant monument even in the papal necropolis, meaning the Basilica of San Pietro in Vaticano. It is also hard to believe that, it immortalizes the pope who had not distinguished himself in any special way, one who held power in the Vatican for merely twenty-eight months. However, the monument was to not so much immortalize him but more importantly serve another much more pragmatic purpose – a propaganda and advertising one. Indirectly, it reflected not so much the power of the deceased pope, but of someone who was afraid to lose his power.

However, before we get to that let us take a closer look at the monument itself, which actually commemorates the final resting place of two representatives of the Ludovisi family. It is located in the right nave of the Jesuit Church of Sant’Ignazio – near the main altar. It is here that a sort of a chapel was created, that can be reached from the main entrance, passing several other chapels, or through a (presently closed) side door, located on the right side of the chapel itself. In the Ludovisi Chapel, we will see a funerary monument by the wall and the allegories of virtues surrounding an oval space – Courage, Justice, Strength, and Prudence, completed by the skilled continuator of the work of Gian Lorenzo Bernini – Camillo Rusconi. However, let us concentrate on the funerary monument of the pope, made out of multi-colored marble. The dominant element of the whole architectural and sculpture concept seems to be the colorful marble curtain, blue on the outside, and reddish on the inside, decorated with exceptionally rich gold fringes. Placing the monument not in a niche, as was customary for those types of creations, but with two Corinthian columns in the background, which were covered with an illusionist curtain, seems to be quite interesting – a trick that causes an illusion, that there is something hidden behind the columns – it would be enough for the curtain to fall and we would be able to see further areas of the church. We are also under the impression that we are looking at a free-standing monument.

When our eyes stop wandering and “settle down” shocked by the sheer amount of excitement, we will notice the white figures of the main protagonists of this Baroque theatre: the enthroned pope, under a baldachin, blessing the faithful, and two winged personifications which accompany him, of Fame, with trumpets in their hands, of course proclaiming the fame of the pontifex, as well as – seated below (on both sides of the papal sarcophagus) – allegories of Religion and Abundance. The snow-white statues seem to deny the laws of gravity, while the papal monument, set high above, appears to be rising, levitating even. In the lower part of the pope's funerary monument, there is a medallion with the image of the nepot – Cardinal Ludovico Ludovisi. He is accompanied by two putti supporting the curtain surrounding the portrait. One of these is putting out a torch, which symbolizes the end of the earthly journey of the cardinal.

Both the clergymen immortalized on the monument were connected with the Order of the Jesuits – Pope Gregory XV, began his career in the Jesuit Collegio Romano, and during his pontificate, he supported the Society of Jesus. On the other hand, his nephew, who at that time amassed a great fortune, was a pupil of this school and a protector of the order. Both of them surrounded themselves with Jesuits and cooperated with them closely. There was a reason that during the pontificate of Gregory XV, two Jesuits attained sainthood (Ignatius of Loyola and Francis Xavier). The Jesuits also received significant posts in the papal Curia, as well as privileges and the pope's support in their far-East missions. In 1626 the pope initiated the construction of the Church of Sant'Ignazio offering the Jesuits an exorbitant at that time amount of two hundred thousand scudos, while also not forgetting about them in his will, offering further donations. It was the dream of the cardinal to build a church, which would be a great monument to commemorate the Ludovisi family and pope Gregory XV, but also would be proof of the close ties between them and the Jesuits. This is further underlined by the inscription placed at the feet of the enthroned pope: ALTER IGNATIUM ARIS – ALTER ARAS IGNATION, which means: “One [pope Gregory XV] placed Ignatius upon the altars, while the other [cardinal Ludovisi] raised altars to honor Ignatius [of Loyola]”.

When, in his will, he ordered a monument to be erected honoring himself and the pope, the cardinal asked the Jesuits to watch over the design. However, the Ludovisi family was not interested in financing the monument, or at least they successfully avoided it for decades. It must be added, that the family's descendants no longer resided in Rome and they did not need to emphasize their importance in the city. After an embarrassing, for both sides quarrel between the order and the heirs of cardinal Ludovisi, over money that was to be shelled out for the construction of the monument the Jesuits were finally successful in "squeezing out" the appropriate amounts. This took place eighty years after the cardinal's death and nearly one hundred years after the pope's death.

It must be assumed that the Jesuits were not only driven by gratitude towards their benefactors and the founders of their church, but also by political farsightedness. At that time (the beginning of the XVIII century) dark clouds began to gather over their heads. They were reprimanded for the methods they used in the evangelization of China and on the Malabar Coast of India. They were accused by the Dominicans and Franciscans (active in those regions) of excessive adaptation of their missions to the customs of the local populace (acculturation), which would threaten the very dogmas of the faith. The Jesuits were heavily criticized from all sides, while accusations of arrogance and disobedience towards the pope came from everywhere, also from France which did not hold them in high regard. Pope Clement XI expressed dissatisfaction with the Jesuit methods and the Inquisition became interested in them. Forced into a counteroffensive, in the funerary monument of their former protector they saw a weapon, that could be used in a political manner. In honoring him, they accentuated their traditional, unbroken bond with the Holy See. It was Pope Gregory XV, who trusted their methods of running missions in India, Japan, and China, placing Francis Xavier upon the altars. This missionary gave the Church tens of thousands of new faithful. Another Jesuit, Matteo Ricci, with the support of the Holy See, successfully carried out missionary work in China "adjusting" evangelization to fit Chinese rituals. Both the monks adapted elements of local culture since such a procedure decisively aided in their mission and accelerated it.

In creating a monumental statue for “their” pope, the Jesuits placed the current pope Clement XI in a difficult situation – as the one, who had wanted de facto to put a stop to their effective and praiseworthy activities. When in truth the Society of Jesus, a faithful servant of the pope, only fulfilled his will and provided the Church not only new faithful but also material resources. This is what the allegory of Abundance (Abundantia) placed at the side of the sarcophagus, speaks of, accompanied on the other side by Religion. Their figures are a reference to the development of faith and increase in riches, which were a direct result of the cooperation between the Bishop of Rome and the Jesuit Order.

The author of the concept of the monument was the then-favored artist of the Jesuits Pierre Le Gros. The artist won over the hearts of his protectors by completing several years prior, the sculpting group entitled The Triumph of Religion Over Heresy placed in their principal church – the Il Gesù. The dynamism, expression of gestures, and virtuosity of execution of the aforementioned group resulted in the Jesuits entrusting him with subsequent commissions. In 1709 Le Gros began working on the funerary monument. The commemoration of the pope and his nepot on a single monument was a unique undertaking, one that in reality aroused much skepticism in the time of the slowly growing, but nevertheless present criticism of nepotism. However, this did not bother the Jesuits. The sculptor created not only the concept but completed most of the sculptures present in it, besides two allegories of Fame (in the upper part, with the trumpets), which were completed after 1713 by another French sculptor – Pierre-Étienne Monnot. That year a conflict developed between the Jesuits and Le Gros, and as a result, Monnot was employed. It was he who ultimately completed the monument in 1717.

This is the last such monumental funerary monument completed in Rome – a final act of the play commemorating popes, and in this case also their important protégées. Ultimately, albeit only for a brief time, the Jesuits lost this battle. Fifty years after its unveiling the order underwent dissolution and disappeared until 1814.

If you liked this article, you can help us continue to work by supporting the roma-nonpertutti portal concrete — by sharing newsletters and donating even small amounts. They will help us in our further work.

You can make one-time deposits to your account:

Barbara Kokoska BIGBPLPW 62 1160 2202 0000 0002 3744 2108

or support on a regular basis with Patonite.pl (lower left corner)

Know that we appreciate it very much and thank You !