The ancient Greeks, who acquired their knowledge of a person with two genders from the cultures of the East, did not know much about a hermaphrodite if we were to judge by Plato's dialogue. In his Symposium we can read: “ In the beginning, there were three human genders, not just the present two, male and female. There was also a third one, a combination of these two; now its names survives, although the gender has vanished. At that time, you see, the word ‘androgynous’ really meant something: a form made up of male and female elements, though now there’s nothing but the word, and that’s used as an insult”. Three centuries later, meaning in the I century B.C., the Greek historian Diodorus Siculus wrote about a mythical Hermaphrodite, born out of the relationship between the god Hermes and the goddess Aphrodite – hence the name. He also mentioned, that her body is delicate and beautiful, like that of a woman, but it also possesses male features, and masculine vigor; The Sicilian also added: “But there are some who declare that such creatures of two sexes are monstrosities, and coming rarely into the world as they do have the quality of presaging the future, sometimes for evil and sometimes for good” (Bibliotheca Historica, IV). A hermaphrodite, therefore, was someone who was not favored by all, and not all Greeks considered him a perfect creature, even if he was gifted with supernatural senses. The divinity of the Hermaphrodite can be further testified to by his cult, widespread in such Greek cities as Halicarnassus (present-day Turkey) and Athens. We do not know much about him, but it is assumed that this deity was an important "element" of wedding rituals – it accompanied the newlyweds from the wedding ceremony all the way to the act of loe which concluded it, and during which they came together as one – physically and legally. The Greeks put a great emphasis on both these acts, perceiving them as a foundation of social stability – the start of a family, whose main task was to have many children.

In Roman times the Hermaphrodite was recalled upon the pages of his Transformations by Ovid (Book IV, Chapter IV) and it was he who introduced this unusual figure back into culture, changing many of the things which the Greeks had written about it. Following the footsteps of Diodorus Siculus, the poet repeats the story of Hermaphrodite's parents (Aphrodite and Hermes), and then he begins weaving his fantastic tale. In his version Hermaphrodite who was initially just a boy, at the age of fifteen left his home and in Karya on the Ionian coast, met the nymph Salmacis, who lived in a spring named after her. This meeting changed the lives of both of them forever. The nymph fascinated by the beauty of the boy fell in love with him, but because she was unable to win his affection, she came up with a devious scheme. When Hermaphrodite was bathing in the spring, she threw herself in the water, embraced him with her arms, attaching herself to his body so that nobody could separate them. Turning to the gods she begged that they could remain as one for eternity. Her pleas were answered, and it was in this way that a being was born, who was neither a man nor a woman. The gods also decided that any man who would bathe himself in the waters of the spring would forever lose half of his masculinity.

How should we understand this tale? What is the meaning behind Salmacis forcefully making the boy hers, coercing him to be submissive, and on top of that making him feminine? Would his life from now on be imprisoned but fulfilled since it would be bereft of sensual desires? Did the metamorphosis which occurred in the waters of the spring, create an ideal state of eternal fullness and fulfillment, while the joining of souls and bodies, forever removed the pain of separation and parting? Here is where a sort of ambivalence comes into play because according to the hierarchy of values professed by the very strictly patriarchal societies (Greece and Rome), which strongly believed in the superiority of manly activities over passivity, the femininity and inactivity of Hermaphrodite condemned him to scorn and even damnation. Ovid does not provide us with an answer.

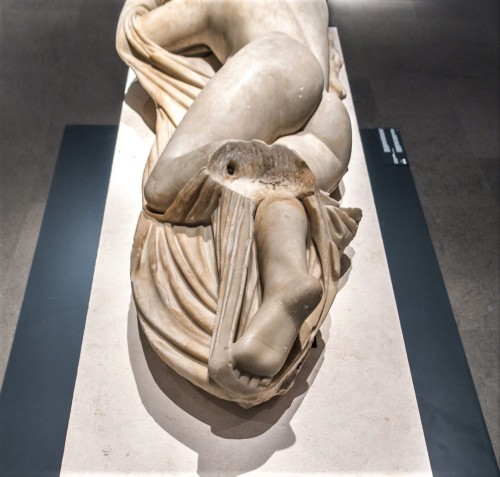

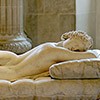

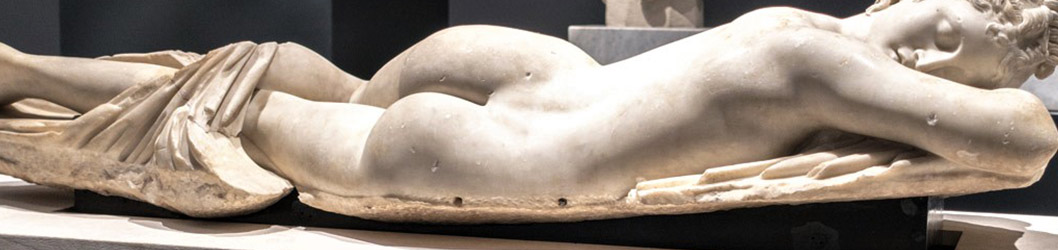

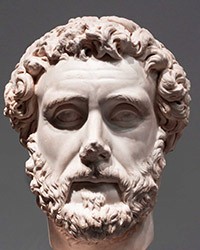

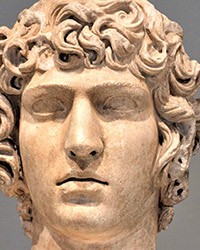

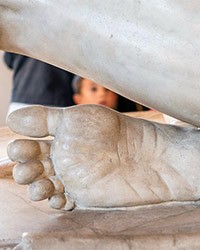

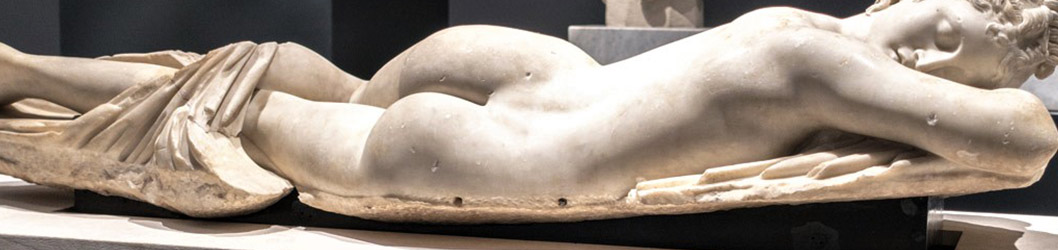

The topic of joining the bodies of Hermaphrodite and the nymph Salmacis became a fashionable motif in Roman art, especially during the times of the emperors Hadrian and Antoninus Pius. We will see it on the walls of theaters, baths, gymnasiums, and gardens, in which people rested and enjoyed erotic freedom. And here, we can return to our sculpture from the Roman Palazzo Massimo. It was made during the Roman times (II Century A.D.), based on an unpreserved Greek original (bronze), dated as II century B.C. Its principal element, besides a purely erotic aura, was the effect of surprise which the onlooker experienced. Approaching the sculpture from the back, we can be under the impression, that right before our coming a beautiful sleeping woman (due to the heat) removed the sheets covering her body. We see the delicate arch of her hips, full buttocks, and the dip in her waist. One of her legs is straightened out, the other bent. The head faces us. We can notice the delicate features of her face and the hair coiffed with finesse. But in changing the position of her body, she has gently raised her thigh covering… the male genitalia. We were convinced that we are looking upon a sleeping woman, yet – approaching from the other side – we see that it is a beautiful young man, although – to our surprise – he also has… a woman's breast. We must admit that the ancient Greeks reached the pinnacle of sculpting art, and the Sleeping Hermaphrodite is one of the most refined examples of this. And it is not simply about the way, that the artist is playing with our senses – surprises us and draws us in with the ambivalence, but also with the ideal beauty of each part of the body of the sculpted figure – the grace embodied in the delicately weaving line, which runs from the top of her head to the arms, hip, all the way to the raised (unpreserved) foot.

The sculpture was discovered in 1879 during the construction of the Roman Opera House (Teatro dell’Opera). At that time, a luxurious garden belonging to a similarly exquisite house was discovered, although the owner could not be identified. Recently the sculpture underwent conservation, but as opposed to other previously found sculptures, there were no attempts made to embellish it or finish it off, although it does have numerous parts missing. On the surface of the marble, we can notice depressions and scratches. The lower part of the left leg, two toes, and part of the bedsheets are missing. It was left as it had been found with no base surface – most likely it rested on natural stone placed in the peristyle of the house.

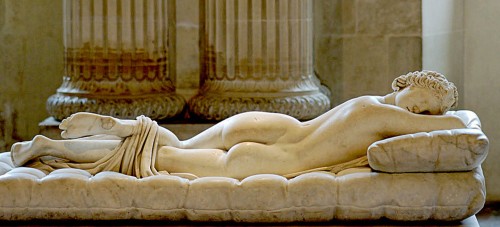

The Greek sculpture of the sleeping Hermaphrodite fascinated the Romans, which can be testified to by the discovery of, up to now, seven replicas of this motif from among which the best-known is the one from Louvre (the so-called (Hermaphrodite Borghese). The story of this artifact is connected with the Eternal City and Cardinal Scipione Borghese – the nepot of Pope Paul V and

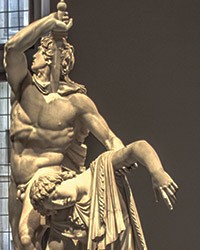

an influential art collector, the founder of the art gallery which exists to this very day and which has been named after him (Galleria Borghese). In 1610, during works on the construction of the Church of Santa Maria della Vittoria, a statue of a sleeping Hermaphrodite was found, which had immediately aroused great interest of the cardinal. He bought it from the church owners (the Carmelites), in exchange for promising to pay for the façade of the new church. The sculpture found its way into his collection and was restored, repaired, as well as enriched by a broad, quilted mattress – the work of Gian Lorenzo Bernini.

It was stored in a wooden chest, in order not to shock the eyes and not to confuse the senses of the unworthy, it was designated for contemplation by the few chosen ones – friends of the cardinal and artists whom the nepot met with in this place. The work remained in the collection of the Borghese family until 1807 when the brother-in-law of Napoleon, Prince Camillo Borghese sold it along with other sculptures to the French. The loss was probably not too great for the prince as the family collection contained another, nearly identical copy, which had remained unknown until the mid-XVIII century. Conserved and repaired it was located in the Borghese family palace (Palazzo Borghese), and then it enriched the Galleria Borghese collection, in a way replacing the sculpture that had been taken to France. It was also supplemented with bedsheets and a mattress, and most likely also a head, completed by the sculptor Andrea Bergondi in the middle of the XVIII century. Today it can be admired there in a room decorated specifically for that purpose (The Hermaphrodite Room), whose ceiling is decorated with frescoes referencing Ovid's story. Unfortunately, the sculpture is located directly next to the wall (!) which makes it impossible to see, behind the beautiful form of the nude buttocks and the slender waist, the dual sexuality of the represented figure.

It is assumed that both the sculptures, (the one from the Louvre, and the one from Galleria Borghese), were located in the Baths of Diocletian and it was there that they were discovered in the XVII century and then purchased by the cardinal – the admirer of antique sculptures and Ovid.

But Scipione Borghese was not the only one who had a weakness for Hermaphrodite. The topic had attracted many artists since the times of the Renaissance, and in the XVIII century, this representation became one of the most often copied ancient sculptures. It was seen as an illustration of an imagined myth as well as charming beauty, and most likely nobody had any notion of the medical context hidden behind this mythological story. Today our medical knowledge about the phenomenon that was previously known as hermaphroditism and today is called intersexuality, is sufficient enough to deconstruct the myth about Hermaphrodite and see in it, people who had for centuries struggled with a sexuality disorder. They are not some figments of our imagination and phantasmagorias, but people who live among us, and struggle daily with their corporeality and sexuality and in addition with the disapproval of people, for whom otherness has always been perceived as a threat.

Sleeping Hermaphrodite, Museo Nazionale Romano, Palazzo Massimo alla Terme, Roman copy from the II century, white marble, 25 cm x 148 cm.

Sleeping Hermaphrodite, Galleria Borghese, Roman copy from the II century, white marble, 162 cm x 172 cm (along with mattress), supplemented in the XVIII century

If you liked this article, you can help us continue to work by supporting the roma-nonpertutti portal concrete — by sharing newsletters and donating even small amounts. They will help us in our further work.

You can make one-time deposits to your account:

Barbara Kokoska BIGBPLPW 62 1160 2202 0000 0002 3744 2108 or support on a regular basis with Patonite.pl (lower left corner)

Know that we appreciate it very much and thank You !