Bernini’s Colonnade – to strengthen faith, Enlightenment and to convince the infidels

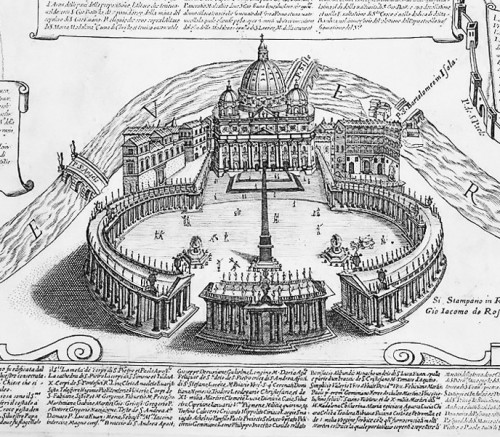

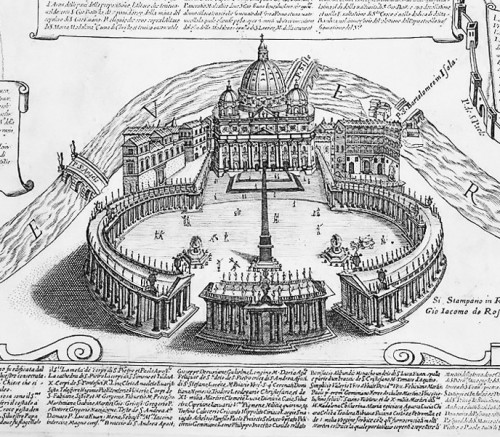

Aerial view of st. Peter's Square, pic. from 1922

View from the dome of St. Peter to St. Peter's Square and Bernini's colonnade

View of st. Peter's Square

View of the St.Peter dom façade

Colonnade in St. Peter Square, Gian Lorenzo Bernini

Colonnade in St. Peter Square, Gian Lorenzo Bernini

Colonnade in St. Peter Square, Gian Lorenzo Bernini

The attic crowning the colonnade in St. Peter's Square designed by Gian Lorenzo Bernini

The attic crowning the colonnade in St. Peter's Square, Gian Lorenzo Bernini

The attic crowning the colonnade in St. Peter's Square, Gian Lorenzo Bernini

Obelisk Vaticano in St. Peter's Square

St. Peter's Square

Fragment of the facade of the Basilica of San Pietro in Vaticano and the colonnade with the coat of arms of Pope Alexander VII

The attic crowning the colonnade in St. Peter's Square, designed by Gian Lorenzo Bernini

The colonnade in St. Peter's Square, designed by Gian Lorenzo Bernini

The attic crowning the colonnade designed by Gian Lorenzo Bernini

View of Bernini's colonnade from the outside

Bernini's colonnade in St. Peter's Square

Columns from the colonnade in St. Peter's Square designed by Gian Lorenzo Bernini

Statues of saints in the attic of Bernini's colonnade, St. Peter's Square

View of St. Peter dom before the uprising the colonnade, Jacob van Swanenburgh (1628), Papal procession in front of St. Peter, pic. Wikipedia

The unrealized design of the portico closing the colonnade in St. Peter's Square, designed by Gian Lorenzo Bernini, pic. Wikipedia

Design of the portico closing Bernini's colonnade in St. Peter's Square, pic. Wikipedia

Via della Conciliazione from the time of Mussolini leading to St. Peter dom

Its grandeur is best appreciated, looking on from the perspective of the dome of St. Peter's Basilica. In front of our very eyes stretches one of the last monumental works of the Baroque – a symbol of the significance of the Holy See and its representative on Earth - Pope Alexander VII. It was he, who ordered his trusted architect Gian Lorenzo Bernini to begin work on shaping the square in such a way so that it would astound and arouse respect. Both the pontifex and his architect succeeded in this task.

Its grandeur is best appreciated, looking on from the perspective of the dome of St. Peter's Basilica. In front of our very eyes stretches one of the last monumental works of the Baroque – a symbol of the significance of the Holy See and its representative on Earth - Pope Alexander VII. It was he, who ordered his trusted architect Gian Lorenzo Bernini to begin work on shaping the square in such a way so that it would astound and arouse respect. Both the pontifex and his architect succeeded in this task.

And now we must imagine this place at the beginning of the XVII century. The Basilica of San Pietro in Vaticano had finally been finished, while the one who brought this about, meaning Pope Paul V, had his name engraved on the façade of the fronton, as if he wanted to forget that the church was a joint work of numerous popes, starting with Julius II. In those times, the pope's megalomania was ridiculed by Pasquino, claiming that the name of Christ, or at least St. Peter would have been better suited.

The monumental basilica was finished, but in front of it was just barren ground, separating the church from the densely populated Borgo with its narrow and dark alleys. The aforementioned Pope Alexander VII and his outstanding architect Gian Lorenzo Bernini enthusiastically began their work in 1656. They were both initiators of this extraordinary undertaking. Bernini’s drawing which has been preserved shows us his idea – the creation of an elliptic square (Piazza di San Pietro), which would be surrounded by a colonnade similar to Christ's arms. It is like a giant amphitheater in the center of which the faithful find themselves in the embrace of their Church. But not simply they – since as Bernini wrote – the square and the colonnade were to strengthen not only the Catholic faith, but once again accept heretics, and "enlighten" the infidels "in their faith".

We can only imagine the magnitude of this task, aimed at the creation of something so monumental without making any cardinal mistakes – so as not to burden the square with columns that are too large and to capture the appropriate proportions. It was also no simple task to find a veritable army of workers to work on such an enormous undertaking. And here is where the pope came to the aid of the architect. As an enemy of beggars and vagabonds, who surrounded the area around the basilica, he came up with an ingenious idea: instead of begging on the streets, they were going to work. The situation of the Romans was also difficult. An epidemic of the plague, which fell upon the city, decimated its inhabitants and left many without any means of living. Working on the construction of the colonnade became for the pope not only his gift to God but also a way to rid Rome of unemployment and poverty.

The colonnade designed by Bernini consisted of 284 monumental, 15-meter-high columns, and 88 pilasters. They were designed in such a way, so as not to detract the viewer's eyes from the basilica, but to elevate it further, but also to close off the square with a line of quadruple covered pillars. The roof was to serve the pilgrims as a resting place (often at night), but also as a place to celebrate procession. Initially, it was planned to put Corinthian capitals on top, but in the end, Doric ones – simple in form – were used. The columns themselves do not possess the same cubature and profile. They narrow gradually – that is why standing at the two points marked in white between the obelisk (Vaticano Obelisk) and the fountains (Fontane di Piazza San Pietro), we can observe a strange optical illusion. The four columns seem like one.

The colonnade was finished off with an attic, which is decorated with hosts of saints – the heroes of faith. One figure placed upon each of the columns – there are 140 in total and they are approximately 3 meters high. On the left (with our back to the basilica) we can see martyrs of early-Christian times and founders of orders, on the right we notice the younger ones – popes, bishops, and modern saints. It was Bernini’s idea for the faithful facing SS. Paul and Peter immortalized in statues and having in front of them the façade of the most important house of God in the world, in front of leaders of the Church chiseled in marble, to feel safety and a sense of belonging.

The figures were Bernini's idea, but their design and completion were undertaken by two of his students – the sculptors Lazzaro Morelli and Giovanni Maria de Rossi along with their workshops. Some of the sculptures were completed in the XVII century, others between 1700 and 1721, during the pontificate of Clement XI. The process of their creation was interesting indeed. Ready-made blocks of marble, cut to the assumed size of 3 meters, were first roughly processed in a warehouse established on the Vatican known as Santa Marta. Then they were placed on top of the colonnade to finish the work under the open skies. Nearly completed, they were taken down to the warehouse once again to be finalized, refined and polished. Each of the figures is an independent work of art, unfortunately for the eyes of the viewer, looking on from the perspective of the square it is practically inaccessible. Besides all these the attic is decorated with the coat of arms of Alexander VII (six mountains in a pyramid and an oak tree) which repeats itself in six places and is a testimony to the significance of the Chigi family.

The colonnade itself was to be finished off with a portico planned by Bernini, closing off the square from the side of the Borgo. Its goal was to produce an effect of surprise. Coming out of the narrow alleys of the Borgo, the visitor suddenly found himself in front of the portico, and was to be charmed by the almost theatrical staging of this location. However, after the death of Pope Alexander VII in 1667 this part was not completed, while subsequent centuries brought about a thoroughly different solution. It was created rather recently, during the times of Benito Mussolini, due to the destruction of the so-called spina, meaning the buildings found between the square and the coast of the Tiber. In this way, the arrangements we are familiar with today were completed, in which Bernini’s colonnade turns directly into the Piazza Pio XII, and then into the monumental via della Conciliazione, created in the 1930s. Therefore, instead of an effect of surprise, which Bernini had planned, we are able to see the façade of the basilica from afar, while the broad street leading up to it as a sort of an overture which brings us closer to Bernini’s work.