Caravaggio’s Conversion of St. Paul – meaning how Saul became Paul

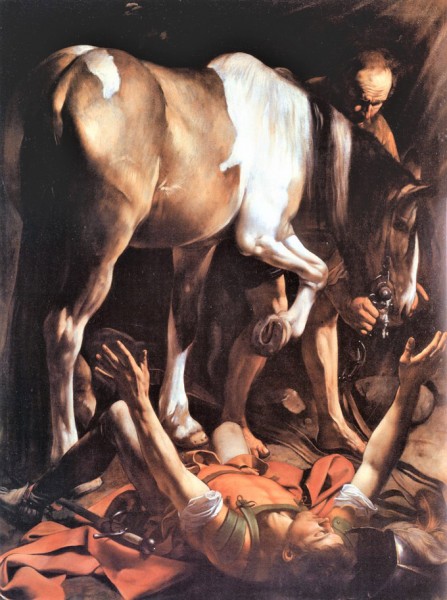

The Conversion of St. Paul, fragment, Caravaggio,Cerasi Chapel, Basilica of Santa Maria del Popolo

The Conversion of St. Paul, fragment, Caravaggio,Cerasi Chapel, Basilica of Santa Maria del Popolo

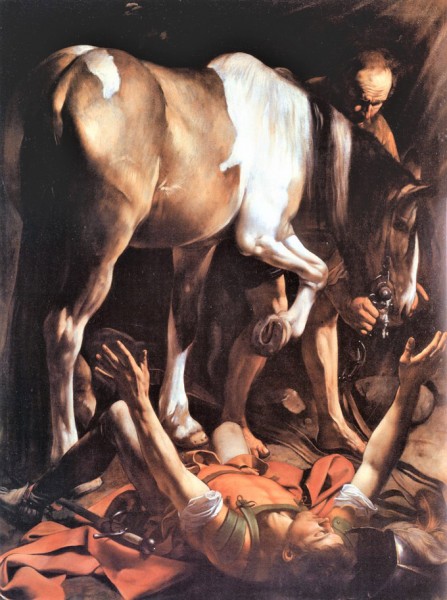

The Conversion of St. Paul, Caravaggio,Cerasi Chapel, Basilica of Santa Maria del Popolo

Conversion of St. Paul, initial, rejected version, private collection of the Odescalchi family, Palazzo Odescalchi, Rome, pic. Wikipedia

Caravaggio can breathe a sigh of relief. The long-awaited breakthrough in his artistic career has finally come about. In the freshly consecrated Contarelli Chapel (Church of San Luigi dei Francesi), he has proven his talent as a painter of multi-figure scenes, full of expression and emotion. His next commission is soon to follow – this is the work on two paintings (The Conversion of St. Paul, The Crucifixion of St. Peter) in the Cerasi Chapel in the Basilica of Santa Maria del Popolo.

Caravaggio can breathe a sigh of relief. The long-awaited breakthrough in his artistic career has finally come about. In the freshly consecrated Contarelli Chapel (Church of San Luigi dei Francesi), he has proven his talent as a painter of multi-figure scenes, full of expression and emotion. His next commission is soon to follow – this is the work on two paintings (The Conversion of St. Paul, The Crucifixion of St. Peter) in the Cerasi Chapel in the Basilica of Santa Maria del Popolo.

Is there a better summary of Caravaggio’s works than the words of Christ himself coming from the Gospel according to St. John: “I am the light of the world. Whoever follows me, shall not walk in darkness, but shall have the light of life” (I, 8.12).

In September 1600, Caravaggio signed a contract obligating him to complete two paintings on wood; his client was the former papal treasurer and a patron of arts, Tiberio Cerasi. The artist began his work with the painting, which was to illustrate the scene described in the Acts of the Apostles, in which the Jewish slayer of Christians Saul, on his way to Damascus sees a great brightness beaming from the heavens and hears a voice: “Saul, Saul, why do you persecute me?” Upon hearing these words Saul asks: “Who are you Lord?”, and the voice responds: “I am Jesus the Nazarene, whom you have persecuted”. The task of the painter was to, therefore, capture the moment of the miraculous transformation of the persecutor into the persecuted, thus giving rise to the greatest after St. Peter apostle, who was the one truly responsible for the creation of the power of the Catholic Church.

Work on the painting did not progress as the artist would have liked – he started drinking once again, wandered around the city with his companions, got into fights. Finally, he was able to finish the work (1601), however, it did not gain the necessary approval. Whether the reason for this was the composition itself, its content, or perhaps a lack of sketches, which the artist had promised to provide, we do not know, but there are various hypotheses. Caravaggio used images of this scene with which he was familiar, aiding himself with Raphael’s cartons and the fresco of Michelangelo in the Pauline Chapel in the Apostolic Palace. In both these works, Christ emerges from the heavens, while light illuminates the figure of Paul. Caravaggio's composition set in a landscape is on the other hand filled with figures: Saul blinded by the light with a long beard, covers his eyes with his hands, while the frightened horse turns away its head, and Christ shown in half-figure, supported by an angel, descends upon Saul from above, while a disoriented soldier directs his spear at him. The painting is chaotic, while the miraculous event is lost in the numerous elements of the armor, feathers, branches, and human gestures, accentuated by the light. Some historians point out the fact, that it was not so much the composition itself which was the object of criticism, but more so the iconography of the painting. Perhaps, the reason for disapproval was the rather direct combination of the divine with the world of the Roman soldiers with one of them seemingly ready to pierce Christ's body with his spear. On the other hand, the gesture of Saul's hands, covering his face, could have been interpreted as a rejection of divine intervention, and not an act of subjecting oneself to God. Other researchers indicate the fact that the painting was unfit to be placed in a small chapel, which did not provide the proper perspective for viewing such an extended composition.

The painting was rejected but we may assume that Caravaggio was not too deeply disappointed by it since he quickly found a willing buyer (private collections, Palazzo Odescalchi, Rome). He began working anew. This time he painted on canvas. He drastically reduced the number of figures – apart from Saul, his vision included only the stubborn horse and an old stableman, with tired, pierced with veins legs. Christ appears here, solely in the form of light, which seems to brighten the souls and minds of the infidels and it is a sign of the coming salvation. Saul himself, this time depicted as a young man, does not cover his face with his hands, on the contrary - he directs his outstretched arms towards the light. The painting amazes with its selection of elements. The unsaddled old horse is definitely in a dominant position. Its hoof raised gingerly, in order not to injure the prostrate Saul, seems to be affected by the same power of the light. The stableman holding its reins, however, does not seem to notice the miracle taking place right in front of his eyes. He does not hear the words of Christ, does not notice the brightness descending onto the protagonist who has been thrown off his steed, he is stuck in his own world. It should not be surprising – this unexpected, mysterious illumination which is at the same time a transformation cannot be comprehended since it is accompanied by the mystery of faith.

The helmet and sword lying next to Saul’s head, seem to symbolize the destruction of the pagan world. Shadow and darkness, meaning doubting God’s grace and salvation as well as fear of death, give way to the light. Thanks to divine illumination Paul is born – a future Apostle of the Nations, a pilgrim walking from one Jewish commune to the next to bring forth the Word of the Lord, a wanderer at the mercy of the faithful. As he writes in his Letter to the Ephesians (3,8), “Although I am less than the least of all the Lord’s people, this grace was given me: to preach to the Gentiles the boundless riches of Christ.” Therefore the removal of shadow and darkness which had been entrusted to Christ has now been given as a gift to his continuator – St. Paul.

The Conversion of St. Paul, 1601, oil on canvas, 230 cm x 175 cm, Cerasi Chapel, Basilica of Santa Maria del Popolo

The Conversion of St. Paul, 1601 (initial, rejected version), oil on cypress wood, 237 cm x 198 cm, private collection of the Odescalchi family, Palazzo Odescalchi, Rome