Piazza del Popolo – the calling card of the city: a prestigious, elegant and representative location

Piazza del Popolo, view from Pincio Hill

Piazza del Popolo, one of the lions adorning the Flaminio Obelisk

Piazza del Popolo, façade of the Church of Santa Maria del Popolo and buildings of the old Augustinian monastery

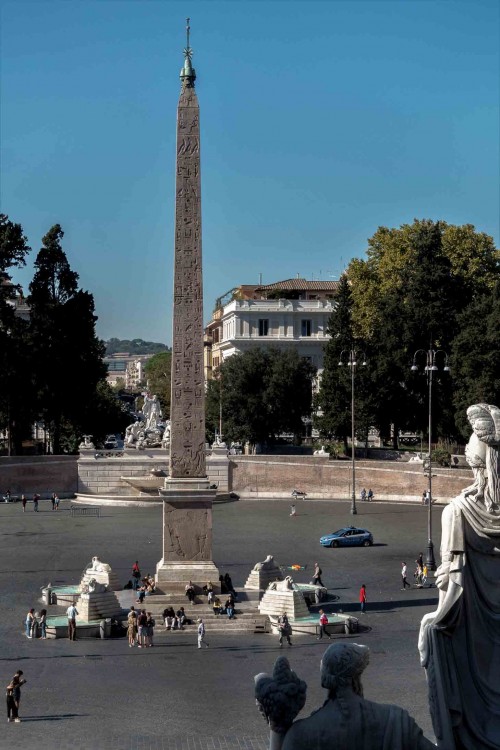

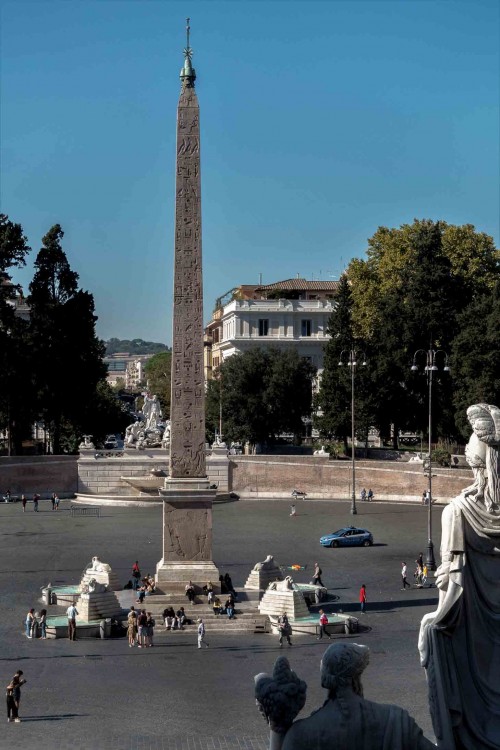

Piazza del Popolo, The Egyptian Flaminio Obelisk erected by Pope Sixtus V

Piazza del Popolo, Porta del Popolo modernized during the times of Pope Alexander VII

Piazza del Popolo, view of via del Corso between the churches: Santa Maria dei Miracoli and Santa Maria di Montesanto

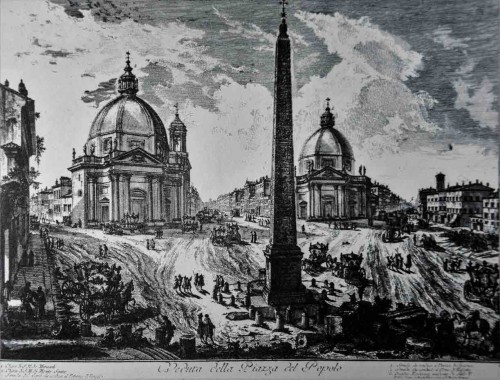

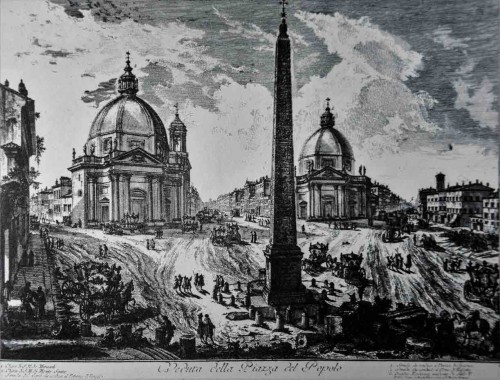

Piazza del Popolo, Giovanni Battista Piranesi, XVIII century

Piazza del Popolo, exedra – the Goddess Roma and the personifications of the Tiber and Arno Rivers

Piazza del Popolo, Neptune and tritons – western side of the square

Piazza del Popolo, view of Pincio Hill

Piazza del Popolo, the goddess Roma and the personifications of Tiber and Arno – eastern side of the square

Piazza del Popolo, Neptune and tritons, decorations of the western exedra

Piazza del Popolo, Lion from the fountain at the Flaminio Obelisk, Porta del Popolo in the background

Piazza del Popolo, Porta del Popolo, Basilica of Santa Maria del Popolo

Piazza del Popolo - southern side – churches: Santa Maria dei Miracoli and Santa Maria di Montesanto

Piazza del Popolo, Flaminio Obelisk

Piazza del Popolo, view from Pincio Hill

Piazza del Popolo, view from Pincio Hill

Piazza del Popolo, approx. 1615, veduta, Willem van Nieulandt, Museo di Roma, Palazzo Braschi

In ancient times, the square was accessed by one of the eighteen gates located inside Aurelian Walls – the Porta Flaminia. It was an important place. Through here emperors and barbarians entered the city, the triumphant, the defeated, generals, pilgrims, travelers, crowned heads of state, and ambassadors. In modern times the square became one of the most representative places in Rome. Its name comes from a church built at the end of the XV century – The Santa Maria del Popolo.

In ancient times, the square was accessed by one of the eighteen gates located inside Aurelian Walls – the Porta Flaminia. It was an important place. Through here emperors and barbarians entered the city, the triumphant, the defeated, generals, pilgrims, travelers, crowned heads of state, and ambassadors. In modern times the square became one of the most representative places in Rome. Its name comes from a church built at the end of the XV century – The Santa Maria del Popolo.

It is here that in 1510, the Augustinian Martin Luther had also found himself, exhausted after a long pilgrimage, but moved and filled with joy, that he had reached his destination, he fell to his knees and greeted the holy city. He lived in the Augustinian monastery, adjacent to the Church of Santa Maria del Popolo. During his time the square was a square, muddy area full of carriages, pedestrians and street vendors. The gate leading onto it, the Porta del Popolo, still possessed its old shape, prior to its modernization, which was conducted in 1560 by Jacopo da Vignola. Nearly thirty years later, Pope Sixtus V, aware of the significance of this place, ordered an Egyptian obelisk (Flaminio Obelisk), to be placed in the middle of the square, which had since that time announced to all visitors that they had safely reached, the rich in tradition Eternal City. The subsequent pope, Alexander VII, requested his trusted architect – Gian Lorenzo Bernini to modernize the gate (Porta del Popolo), which was to constitute the appropriate setting for the prestigious and from the propaganda standpoint very important enterance into the city of the newly converted Christina – Queen of Sweden. He also supported, in the middle of the XVII century, works on the construction of two Baroque churches adorning the square (Santa Maria dei Miracoli and Santa Maria in Montesanto) – the works of Carlo Rainaldi and Carlo Fontana. It was also at that time that three large avenues were set out, which like a trident pierced the chaotic building pattern of the city, providing it with a modern and representative appearance. As a result visitors were greeted not only with a modernized gate, an ancient obelisk, but also, as if another gate, the twin churches dedicated to the Virgin Mary – the symbol of the Roman Catholic Church struggling against the Protestant heresy. Their architectural form is a reference to two important Roman structures – the Pantheon and St. Peter’s Basilica (San Pietro in Vaticano) – it becomes a sort of foreshadowing – an overture for visitors who will soon see the architectural wonders of Rome. It is worth noticing that the bell towers of both the Marian churches were erected from the side of the via del Corso. On one hand they served the purpose of a sign, announcing the destination, a city of religious contemplation and prayer, on the other hand in an almost theatrical way marked the main road to the city center. The aforementioned via del Corso, had since ancient times led to Capitoline Hill. The two remaining streets led to the Vatican and to the Basilica of Santa Maria Maggiore, then further on to the Lateran (Basilica of San Giovanni in Laterano).

Ultimately the final appearance was provided to the square by Giuseppe Valadier, creating in 1822, the still recognizable today, semi-circular form and decorating it with a fountain and lions, which accompany the obelisk. The lions are a copy of ancient sculptures found in the Musei Capitolini. On the sides the square were enriched by Valadier with exedrae and fountains, in this way doing away with the Baroque, elongated axis of the square and stretching it on a lateral axis. From the side of Pincio Hill the semi-circular exedra was enriched by the statue of the standing goddess Roma, at whose feet there is the Capitoline lioness accompanied on either side by the personifications of the Tiber and Arno. On the opposite side we will find the god of the seas Neptune with two tritons (half-man half-fish).

In this way the work of many generations of architects and popes was completed. The final effect had already begun arousing controversy in the XIX century – according to some a concentration in one place of objects of the Renaissance, Baroque and Classicism was for the face of the square a ruinous undertaking, others in this mixture of styles saw an advantage and praised the art of combining various styles into an integral, logical whole. Either way it is difficult to deny, that since that time the Piazza del Popolo has become one of the most elegant, representative and imposing with its grandeur locations in Rome.