Simon Vouet’s Herodias with the Head of St. John the Baptist – femme fatale of the Baroque

Herodias, Simon Vouet, Galleria Nazionale d’Arte Antica, Palazzo Corsini, pic. Wikipedia

Herodias, Simon Vouet, Galleria Nazionale d’Arte Antica, Palazzo Corsini

Salome, Simon Vouet, Crocker Art Museum, Sacramento, pic. Wikipedia

Judith, Simon Vouet, Kunsthistorisches Museum, Wien, pic. Wikipedia

Judith with the Head of Holophernes, Simon Vouet, Alte Pinakothek, Munich, pic. Wikipedia

Femme fatale is associated with painting and literature of the XIX century – with women who devoured the hearts of men, cold-blooded demons of sex who with premeditation led men to their downfall. However, beautiful, erotic, attractive, but at the same time ruthless and sophisticated women have always fascinated artists. We can find them in ancient literature and mythology, as well as in the Old and New Testaments. We can also see them in the painting creations of Caravaggio and his successors because it was exactly in the XVII century when Salome, Judith, and Herodias became fashionable painting topics, which in a special way captured the imagination of men. This came about when art no longer served solely the needs of the Church but became a passion for an ever-growing group of private collectors.

Femme fatale is associated with painting and literature of the XIX century – with women who devoured the hearts of men, cold-blooded demons of sex who with premeditation led men to their downfall. However, beautiful, erotic, attractive, but at the same time ruthless and sophisticated women have always fascinated artists. We can find them in ancient literature and mythology, as well as in the Old and New Testaments. We can also see them in the painting creations of Caravaggio and his successors because it was exactly in the XVII century when Salome, Judith, and Herodias became fashionable painting topics, which in a special way captured the imagination of men. This came about when art no longer served solely the needs of the Church but became a passion for an ever-growing group of private collectors.

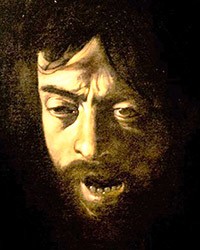

Therefore, it should come as no surprise that the French painter who was active in Rome at that time, Simon Vouet, also wanted to try his hand at such painting. Biblical, bloody heroines have been painted by him numerous times. They look upon us from his paintings with delicate smiles, and if it was not for the attributes visible in their hands – the proof of their crime – we may think that these are simply portraits of attractive women. One such canvas is found in the collection of the Roman Palazzo Corsini. Initially, the painting could not be unanimously attributed – it appeared under numerous titles (Herodias, Salome, Judith). Galleria Nazionale d’Arte Antica ultimately decided that the protagonist of the painting was none other than Herodias.

Skillfully, the painter shows us the lavish golden colors of the satin, shining dress of the queen, which is in direct contrast with the delicate red of her lips, flushed cheeks, and the ribbon in her hair, as well as the intense red of the meaty fabric covering the head of the murdered prophet. Behind her, we can notice a part of the prison wall, where John the Baptist was beheaded, and a fragment of the ominously clouded night sky. Similarly to the landscape, Herodias seems to be an ominous figure, a sinful one. Her first sin was leaving her husband Herod II with whom she had a daughter Salome, and marrying his brother – the ruler of Galilee, Herod Antipas. In the Gospels according to St. Mark and St. Matthew, it was this union, illegal in terms of Jewish law and tradition, that was the reason both the queen and her husband were decried by John the Baptist. The royal couple attempted to silence him with threats and then (at the behest of Herodias) locked him away in a dungeon. The queen felt offended by his criticism and openly desired his death. However, her husband did not agree to it, fearing the anger of the populace, which considered John the Baptist a prophet. This was the case until a feast, during which the young Salome charmed her stepfather with her beauty, allure, and dancing, and he promised to fulfill all of her wishes. It was then that Herodias once again stepped on the stage prompting (Mk 6,24) her daughter to wish for the head of John the Baptist, that she was unable to get herself. After the execution, the head of the murdered prophet was handed to Salome on a platter and she gave it to her mother (Mt 14,11). Herodias could feel fulfilled. And this is the very moment depicted by the painter. The woman's face is a picture of peace, which she experienced after her goal was achieved, but also the satisfaction that her plan turned out so perfectly. The platter on which the head of John the Baptist was placed, was painted by Vouet in such a way that only after a moment – as we draw our gaze away from the beautiful face of the woman, her smile and her flushed cheeks – we can direct our attention to it. The gruesome in itself scene brought together with the beautiful visage of a woman. Not a single drop of blood stains her dress, not one sign informs us of the shameful deed which she was responsible for. The terrible crime took place in an ideally beautiful world, whose symbol is the smiling and looking upon us Bella (Beauty). She is adorned with pearls, a motif that was readily painted by Vouet for all his heroines and which (as a luxury good) proclaim the high status of a woman, although they were also associated with the futility of all that is human, but most of all with womanly vanity and perversity.

What did the painter want to tell us? Did he intend to show the martyrdom of a prophet or the charm of a woman manipulator? We may also ask what was the aim of immortalizing the bloodthirsty Herodias. Who would have wanted to adore such a woman, who would like to rest their gaze upon her? The answer is difficult since it reaches deep down into the human psyche. Before we take this in-depth look, let us become familiar with the circumstances of the creation of this work.

The painting was made for the faithful collector of Vouet’s works – the erudite Cassiano dal Pozzo, a scientist who was a frequent guest at the papal court of the Barberinis, who were themselves, significant art collectors. It is assumed that dal Pozzo's collection boasted fourteen paintings completed by the artist, most of these being the half-lengths of the images of beautiful youths and attractive women, often (but not always) shown as saints with the attributes of their martyrdom. These included Old Testament women – Judith and Salome, whom the artist had painted several times (Judith, Alte Pinakothek, Munich), (Judith, Kunsthistorisches Museum, Vienna), (Salome, Crocker Art Museum, Sacramento, USA). Cassiano dal Pozzo was not only the man who commissioned these paintings, but he also aided Vouet with his advice and intellectual counsel, and in addition, he was an expert on the needs of the then-art collectors.

Coming back to the analyzed painting, we can have no doubts, that it appears to us not as the illustration of a biblical scene, but as an object which serves the esthetic and sensual contemplation. And we may even assume that this physical beauty of the models, dressed as the heroines of biblical and hagiographic stories was the main reason for the creation of these quasi-religious scenes. In the community of Roman art patrons, among which there were mainly cardinals, it was difficult to explain the commissioning of a painting depicting the beauty and allure of the female body. Such Belles were known from the paintings of Titian, who portrayed the seductive Venetian courtesans only for the pleasure of his clients. In Rome, it was necessary to provide an ideological cover-up. The pleasure for the senses was camouflaged by lofty religious topics. Such paintings were in fact completely secular and had nothing to do with religion – they were the fantasies suspended between horror and desire, fear and sensuality. This ambivalence of beauty and evil was fascinating and attractive.

However, in the story of Herodias, there is something more – perversion. A mature matron, this being Herodias in the painting (and that is why it could not be the adolescent Salome) is the perfect image of the then-womanly beauty, however behind her stands yet another object of desire – her delicate, young, and inexperienced daughter. In the game being played by the mother, it is Salome who is the object of Herod's desire – Herodias takes advantage of this situation, in which the daughter arouses the husband's desires and consciously (most likely) makes this possible. She is devious, and cunning and in cold blood puts her plan into effect and it is finished off with the platter with John the Baptist's head.

The painting was created at the height of Vouet’s popularity in Rome. It was then (1620-1627), that the artist’s style acquired liveliness and elegance. We can almost feel how the painter frees himself from the influence of Caravaggio and follows his own path, which will ultimately take him to Paris, and the art created there, full of panache and virtuosity. Here we can only see the budding beauty of his subsequent painting.

Herodias, Simon Vouet (1620 – 1625), oil on canvas, 82 cm x 112 cm, Galleria Nazionale d’Arte Antica, Palazzo Corsini

If you liked this article, you can help us continue to work by supporting the roma-nonpertutti portal concrete — by sharing newsletters and donating even small amounts. They will help us in our further work.

You can make one-time deposits to your account:

Barbara Kokoska BIGBPLPW 62 1160 2202 0000 0002 3744 2108 or support on a regular basis with Patonite.pl (lower left corner)

Know that we appreciate it very much and thank You !