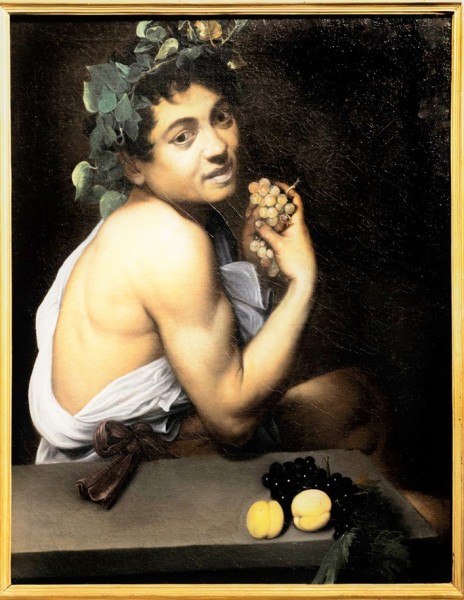

Caravaggio’s Young Sick Bacchus – an artist in the guise or perhaps something much more?

The painting comes from the earliest period of Caravaggio's works in Rome. The accounts provided by the artist's biographers (Giovanni Baglione, Giulio Mancini, Giovanni Pietro Bellori) do not give us any certain information about this period, are incohesive, and sometimes even contradictory. That is why we are left with suppositions and only a few trustworthy sources, which have gradually been found in the Italian archives.

What did the life of Michelangelo Merisi look like prior to coming to the Eternal City? Certainly, it was not easy. At the age of five, he lived through the plague in Milan due to which the family fled to Caravaggio – a small town between Milan and Brescia, where the artist's father and grandparents passed away. The six-year-old boy left his family home and returned to Milan to be educated in the art of painting by master Simone Peterzano. In 1590 Caravaggio's mother died. And these are all the facts we have from the life of the painter until he came to Rome, although even here we cannot be certain when exactly he arrived and why he left Milan. It is assumed that Caravaggio came to the city on the Tiber in the second half of the year 1592 or in 1593, but some historians believe that the event occurred a few years later. What did he do? Mancini writes that during the initial years of his stay he was poor, often changed his accommodations, walked around in rags, lived on the fringes of the great city, and surrounded himself with people of doubtful reputation. This is repeated by Cardinal Federico Borromeo who possessed his painting Basket of Fruit (Brera, Milan). In 1625 in one of his letters, the cardinal describes the painter whom he had met personally prior to 1601, as a fellow with bad manners, dressed in torn and dirty clothing and living among servant boys and wealthy lords. Caravaggio spent his time in taverns among gamblers, drunkards, Gypsies, cripples, porters, and among all those unfortunate enough who spend the nights sleeping on town squares. And probably he knew them all too well, saw them in dark alleys, cheap inns, and brothels, and he placed them upon his paintings, in subsequent years making them the main protagonists of his works.

Initially, he worked for various workshops never staying for too long in one place. According to Mancini for several months he lived at a home of a prelate by the name of Pandolfo Pucci. Caravaggio would go on to call him "Monsignore Insalata" due to the very meager meals that were served there, which consisted mainly of lettuce. In exchange, he provided the prelate with copies of paintings of saints, which the clergyman then distributed. He also created portraits, which Bellori informs us about, writing that in order to survive Caravaggio would paint three "heads" (portraits) a day. Then he would find employment in a noteworthy workshop of the famous at that time painter Cavaliere d’Arpino. His tasks as was fit for an aide were of secondary importance. He added flower garlands to the master’s compositions and created (most likely) elements of still nature, in which Caravaggio was quite skilled. Most likely Young Sick Bacchus and Boy with a Basket of Fruit as well as Boy Bitten by a Lizard were created either at that time or a short while after the two artists parted ways (1595?). We also, do not know, why two of the aforementioned paintings, including Young Sick Bacchus, remained with Cavaliere d’Arpino. Perhaps, as Mancini had claimed, the reason for leaving the renowned workshop was the appearance, in the life of Caravaggio, a painter but above all an intermediary who was active in various Roman communities – Prospero Orsi. He noticed the abilities of his fellow painter, but also the opportunity to make some extra money, being a middleman in the sale of his paintings, which were purchased by merchants (including Constantino Spada), wealthy collectors, and art enthusiasts. Gradually Caravaggio would emerge out of obscurity, and thanks to an influential protector, namely Cardinal Francesco Maria del Monte, he achieved a certain degree of fame. However, we will come to a halt here, remaining with the painting of a young, angry, and poor artist, which was who Caravaggio was during the initial period of his stay on the Tiber.

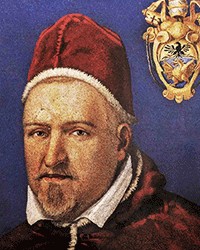

Young Sick Bacchus remained in the collection of Cavaliere d’Arpino until 1606, meaning until the time all the canvases from his workshop were seized by Pope Paul V, to finally find itself in the collection of his nephew, Cardinal Scipione Borghese (a great admirer of Caravaggio's talent). There – described as a "picture with a youth in an ivy wreath crushing grapes in his hand" – it pleased its owner immensely, but after his death, it was lost for centuries in the warehouses filled with his collections. It is worth adding that, Mancini was aware of the painting and called it an image of a "wonderful, beardless Bachus". In the twenties of the XX century, it was discovered and identified by Roberto Longhi – the man who brought Caravaggio back to prominence. And it was he who entitled the canvas “Young Sick Bacchus" due to a sickly green skin tone, pale lips, and an expression of suffering which was difficult to describe, which filled the visage of the portrayed youth.

Currently, historians agree that this is the earliest known portrait of Caravaggio, which we are aware of. According to Baglione, the artist painted a few self-portraits during the early period of his work, "using a mirror", and this one was the first of these. Unfortunately, we do not know of any others. Thanks to the account of a certain barber from 1597, found in a police report, we are presented with an opportunity to compare a description of the artist’s appearance with his portrait. The aforementioned barber remembered Caravaggio as a man with a “thin, black beard, of stocky build, black-eyed, with bushy eyebrows and thick unruly hair, who dressed carelessly, in black, and had worn tights and a worn cape”.

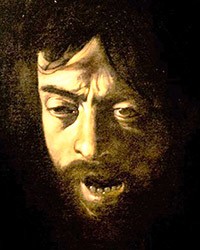

Baglione claimed that the main reason that Caravaggio had painted himself was the lack of money to hire models. And most likely at that time, the artist was completely broke, but certainly, that is not the only reason, since – as we know – he portrayed himself in his paintings numerous times at various stages of his life. Is it then a self-portrait in the guise of all’antica or perhaps something more? Let us look at the work. The youth depicted on it is sitting in an undefined space at a stone table, directly across from the onlooker, and pierces him with his despondent gaze. At the same time, we feel as if he was trying to cozy up to us with his sad smile. Upon his head rests an ivy wreath, while he shows us his bare hands and a part of his back. His short, white tunic is tied with a claret ribbon, whose knot rests on the stone tabletop. There are also two peaches and a bunch of grapes on the table. The second bunch of the freshest fruits is held, or more appropriately crushed by the youth in his palm. Both the still nature and the model emanate with a sort of difficult-to-describe rawness. Instead of a beautiful Bacchus, which was seen hundreds of times in art history, Caravaggio shows as a dirty, sad youth. Ecce homo – he seems to be saying – a boy, one of the thousands who could be seen on the streets of the Eternal City searching for love, a way to make money, and a place to sleep. However, the author also tells the potential viewer: here you see an unwashed model posing for the image of an antique god. In this way, the artist not only distances himself from the canons of art in place at that time but also ridicules them. He exposes the idealized world and shows us the real one, seen on the streets of Rome, one that is much more intriguing in his opinion. Searching for topics, for his compositions, Caravaggio does not find them among the mythological tales in which the beauty of a young, manly body was shown, but rather he focuses on the ambiguous in their message images of Roman boys, who can often be seen in his early works. Slightly feminine, with dreamy eyes (The Musicians), stylized hair, dressed in short, white tunics, with bare shoulders, sometimes with flowers in their hair (Boy with a Lizard), or vine wreaths (Bacchus) they appeared at the courts of cardinals and wealthy Romans, enriching their banquets and concerts. Dressed in such a way and “draped” they sang (The Lute Player), acted in improvised plays, played extras, waited on tables, and served in every imaginable way wanting to gain attention, renown, and money. The all’antica disguise and wreaths upon their heads hid their peasant roots and poverty which nobody had wanted to see. They were only betrayed by their dirty nails. Ennobled in this way, they added to the parties and feasts of to a large extent homoerotic community of the then Roman elites. Our hero – the sick Bachus – is one of them: tired, sleepy, perhaps infirm, he seeks our attention, closeness, and care. It is no accident that the artist places him as near the viewer as possible as if he was offering us not barely the measly fruits, but rather himself. This is one of the protagonists, who were so skillfully portrayed a few centuries later by Paolo Pasolini in the book Ragazzi di vita (The Hustlers). The writer and director encountered them in the suburbs of Rome – poor, ready to provide all kinds of services, including those of sexual nature, which Pasolini readily accepted until he was massacred and killed by one of the “boys”. This is a world similar to that of Caravaggio – filled with human suffering, poverty, and a lack of perspective, one that nobody wants to see, and if it is seen, it is to be quickly forgotten, not commemorated in a painting. Yet this is exactly what Caravaggio does. He shows a youth with a very real physicality, an average appearance, who in a natural way presents his dirty nails, yellowish face, and blue lips.

And indeed, the ambiguity in Caravaggio's paintings turned the heart of more than one painting enthusiast, who sought more in art than simple beauty. These qualities were ambivalence, understatement, and the possibility of multiple interpretations. And Caravaggio recognized this need. He painted for a small group of connoisseurs, who hid their paintings in palace chambers, often behind curtains, protecting them from dust, and sun, but also the wrong eyes. These works were to be a motivation for a discussion in a refined group of people, who met during evenings filled with music and song and were to inspire with their originality and irony, but above all immerse the wealthy in the life of the Roman streets, from the pleasant perspective of the palace salons. Caravaggio penetrated the depths of the viewer's soul and recognized his weaknesses, painted on the border of that which was acceptable and often even crossed that border, but above all he established dialogue with the onlooker. He confronted him with protagonists who were unknown to painting until then, ones that were unworthy of being the subject of art. Who then is worthy to be shown upon a painting? – he asked. Is what I am painting important, or is it more important how I am painting it? Is it necessary for me to flatter you, or should art irritate you, and introduce anxiety and discomfort into your life? Caravaggio, in his painting, seems to articulate the conviction that every aspect of reality is important, essential, and worthy of painting, but the most important is the naturalist showing of the human figure. It is important for it to be painted with the mastery of matter, and that is something he was extremely skilled at. Let us look at the masterfulness of his workshop, the mysterious light operating from the side, bringing the most important elements out of the darkness: the boy's body, the wreath on his head, highlighting the dimness of the grapes, and the rawness of the background. This lack of decorum, one of the most important paradigms of art, had to both provoke and fascinate.

Looking at this painting, still, today historians are creating new interpretations. Some see in it the par excellence allegory of the artist himself – a painter from under the sign of Bacchus, the god of orgy, anarchy, drunkenness, the melancholic and mischievous voyeur, one who could see more and better, an observer and a careful analyst of human nature. And he (Bacchus), similarly to the artist, acts under the influence of divine inspiration, and he embodies the power of destruction, which Caravaggio often succumbed to during his life, full of problems with the law, rows, and fights. Is it therefore the artist trapped in the body of Bachus, who looks upon us in the nightly glow of the moonlight? This interpretation may be correct when we look at the popularity of artistic societies that would call upon the god of fertility and wild nature. And so in Milan, a burlesque Academy of Bacchus was established which brought together the local artists, who saw the deity as their patron. The young Caravaggio had to have known them.

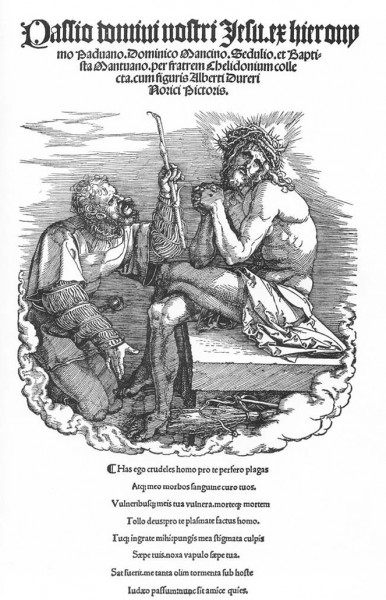

Other historians see in Bacchus the prefiguration of Christ with grapes as the symbols of the Passion. From an iconographic point of view, an interesting trail leads us to the title page of The Great Passion, completed by Hans Dürer – an artist who was greatly valued in Italy, and specifically in Lombardy, where Caravaggio came from. In Dürer's print, we can see the same kind of twist of the body and placement of the arms and legs of Christ, which would later appear in the work of Merisi.

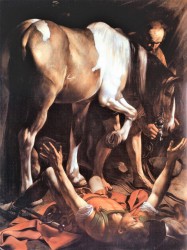

Other historians see in the painting a sort of ex voto, a votive offering for saving the artist from an illness, which befell Caravaggio after he was kicked by a horse, or malaria (most likely), which caused him to be bedridden in a hospital for many months. This was a kind of "secular” resurrection” of the painter, his return to life paid for by suffering.

Which of these interpretations, and there are more, is the most convincing, depends on the viewer. And that is what constitutes the greatness of Caravaggio's painting – it is enough to carefully look upon his works.

Self-portrait in the guise of Bacchus/Young Sick Bacchus, Caravaggio, approx. 1594, oil on canvas, 67 x 53 cm, Galleria Borghese

If you liked this article, you can help us continue to work by supporting the roma-nonpertutti portal concrete — by sharing newsletters and donating even small amounts. They will help us in our further work.

You can make one-time deposits to your account:

Barbara Kokoska

BIGBPLPW 62 1160 2202 0000 0002 3744 2108

or support on a regular basis with Patonite.pl (lower left corner)

Know that we appreciate it very much and thank You !