Such a state of things continued all the way to the XIII century when the square attracted the attention of the representatives of the Orsini family, who built some of their houses on one of its sides. However, its dominant feature was still grass, at least until 1456 when it caught the interest of popes. The meadow which was in no shape or form a match for the splendor of the center of the Christian world, and which gently descended towards the Tiber, during the pontificate of Pope Callixtus III was connected to a network of nearby streets, water was supplied while houses and workshops started to appear around the broad square. A significant event in the history of the square was the construction of Ponte Sisto (1573) – a bridge on the Tiber, which became an important element of a pilgrim track leading from the Trastevere, through the via Bianchi Vecchi, all the way to the Basilica San Pietro in Vaticano. Twice a week, a horse market took place at the square, and in addition, the more and more populous square was a place where important information and public announcements were read, while criminals were punished. At that time it was not flowers and vegetables that were sold, but rather the products of the craftsmen from the nearby workshops. How do we know? Currently, the streets adjacent to the square boast their names – crossbow-makers (via dei Balestrati), coffer-makers (via dei Baullari), hat-makers (via dei Cappellari), tailors (via dei Giubbonari), as well as butchers (via dei Becai), or key-makers (via dei Chiavari).

This place, which boasted a tourist and pilgrim character, quickly became known for its real estate. Taverns and inns, with the graceful names of "Della Neve", "Della Luna", "Dell'Angelo", and "Della Scala" were established both at the square as well as neighboring alleys. Of course, there also had to be room for the ever-present houses of ill repute and palaces of sin. It is here that at the end of the XV century, at number 11-14 (at the corner of Vicolo del Gallo), cardinal Borgia bought the property for his mistress Vanozza Cattanei, and it is here that the children of the future Pope Alexander VI were born and raised. After his death, Vanozza remained here, also purchasing another property along the same street and running an inn named “Albergo della Vacca” (Cow’s Inn), which is testified to by a coat of arms placed on the face of the building (a combination of the coat of arms of the Borgias and the coat of arms of Carlo Canale – Vanozza’s third husband). The prosperous inn was then given over to the Church by the elderly mistress in exchange for three annual masses (for an indefinite period of time) – one for herself and the remaining two for each of her husbands.

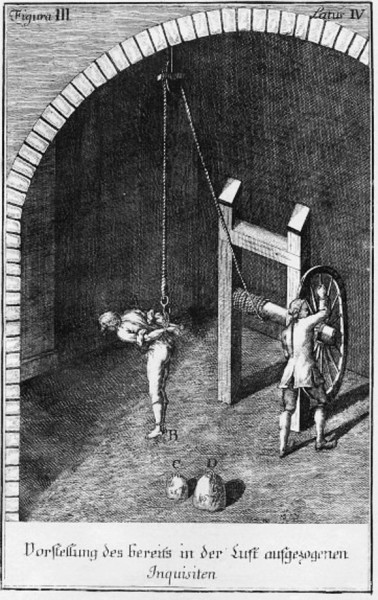

In order to bestow a more representative character to this location, a fountain designed by the renowned architect Giacomo della Porta was placed in the center of the square in 1595. The pool place below the level of the surface was adorned with the sculptures of four dolphins on the sides and was topped off with an oval bowl. Five years later, the fountain was witness to the most famous execution in the history of the city. On this very square, Giordano Bruno’s death sentence was carried out, as had previously been done to other enemies of the Church such as the Franciscan theologian Giovanni Buzio (known as Giovanni Mollio) and his student Teodoro Teodori, who were both deemed as heretics in 1553 and sentenced to death by hanging and then burned. Another heretic, the theologian and scientist Marco Antonio de Dominis did not live long enough to be executed as he died in a Roman prison. However, his texts were ceremoniously burned here in 1624. Burning at the stake took place while maintaining all the rituals connected with it, including a procession attended by singing hooded brothers (members of societies which then occupied themselves with the burial of the criminals), a regiment of soldiers, and of course the ever-present onlookers, who were the principal “benefactors” of this spectacle which was supposed to fill their heart with fear. The guilty person was placed on a pedestal and was accompanied by a hooded figure of an executioner and his assistant, as well as a praying priest, whose main duty was to try and convince the condemned to repent. This was not the only site of executions in Rome. In other areas (Piazza del Popolo, Piazza Navona, Sant’Angelo Bridge) different methods of execution were practiced - hangings, beheadings (punishment reserved for nobles) as well as quartering of the body, while placing the limbs in different parts of the city, including Campo de’Fiori, were common practice. The square was more than an occasional site of death, it was also a place where lighter punishments were handed out. For this purpose, the square had the so-called "pendulum" (a high pole with a long rope), which was mainly used to discipline dishonest merchants. The punishment was based on tying the wrists of the guilty party behind his back and then pulling him upwards only to let him rapidly fall down, which not only caused excruciating pain but also led to the tearing of muscles and ligaments. In order to strengthen the torture, weights were tied to the feet of the condemned. Such events of educational character also enjoyed great popularity among the people who were desperate for the excitement or simply wanted to witness the appropriate punishment. The one with the use of the pendulum was known as "reverse hanging" (il tormento dell corda) and is still recalled today in the name of the via della Corda (Rope Street), which in the past led directly to this instrument of torture.

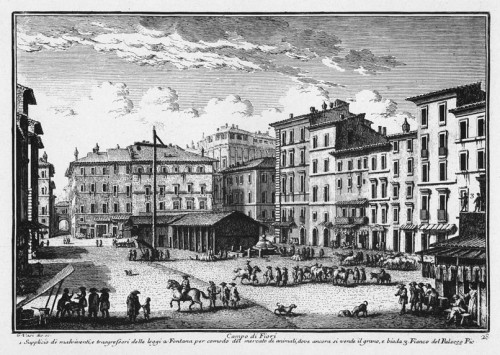

The great engraver and city portrait-maker Giuseppe Vasi shows us exactly what life on the square looked like, documenting its appearance in 1752. On one of his engravings, we can see the aforementioned pendulum and the nearby fountain, which has an altered form. In order to protect it from littering it was covered with a bowl made of travertine (1622), providing it with a form of a terrine, meaning an oval soup bowl, which has since then been ridiculed by the Romans (Fontana della Terrina). On Vasi's engraving, we can see a horse market taking place. There are also food stalls ready to serve hungry visitors, who did not seem to lose their appetite despite the close proximity of the "pendulum".

At the end of the XVIII century, the pole along with the rope disappeared from the square, but a real breakthrough did not come about until 1869. A flower, fruit, and vegetable market was transferred to the Campo de’Fiori, which had until then taken place at Piazza Navona, while the horse market was removed. Since then, six days a week, until noon, the square is covered with stalls selling vegetables, fruits, and flowers. However, Campo de'Fiori is also known for the Statue of Giordano Bruno, erected in 1889 and situated in the exact place where the “rebellious” scientist was burned. The hooded, grim figure of the heretic made out of bronze, which aroused the aversion of the Church, became a great problem, while the story of its creation was a controversial topic among the inhabitants of the Eternal City. For decades the statue was a bone of contention between the pope and the secular authorities of Rome and the Italian state. Ultimately, thanks to Benito Mussolini it remained where it was. However, the statue changed the image of the square itself. As a consequence, della Porta's fountain was taken apart and finally placed in front of the Church of Santa Maria in Vallicella, yet its copy once again graced the square. This time it was erected on one of its shorter sides directly opposite Giordano Bruno. The constructors followed della Porta's design, however, they changed and elevated the lower pool of the fountain.

Today the square which is surrounded by rather inconspicuous and chaotic buildings can be seen in two different ways. One during the day – when filled with all kinds of stalls (no longer simply flower and vegetable), it offers tourists a moment of respite as they are convinced to be in one of the most climactic places in the city. The pyramids of seasonal fruits, piles of garlic and onion as well as the ever-present in the Roman cuisine artichokes, gracefully having their leaves removed with rapid strokes of a knife and then being thrown into the water with lemon in order not to lose their color, are piled high next to enormous pieces of parmesan cheese, dishes full of colorful olives, pesto, and marinates, loudly praised by the vendors. Stalls filled with chunks of tuna and other seafood right beside Chinese products of all kinds are a testimony to the fact that the square quickly adapts to client needs. All of this gives off the sensation of being part of a centuries-long Roman ritual. And above all of this variety towers Giordano Bruno himself, bringing to mind the poem of Czesław Miłosz entitled Campo di Fiori, whose text can be found on one of the plaques exhibited on the square (at the corner of via dei Giubbonari). In 2015 it was placed here once again, after being destroyed by vandals…, which is symbolic in itself.

The other face of the square is revealed at night, when young people with bottles of beer crowd the steps of the statue, exotic vendors offer shiny, plastic rubbish, while the tourists sitting in broad beer gardens sip their drinks or take advantage of the food on offer, taking in the noisy atmosphere of the square. That is probably how Miłosz saw it as well, although when he was here it was not yet the tourist attraction that it has become today. Nevertheless, even then the poet perceived the square as a center of both life and death.

There is still another time of day, perhaps the most fascinating, when the square briefly reveals the third of its faces: this is the time when the vendors have not yet begun to set out their wares, while the grim bronze Dominican towers over the empty marketplace in the grey early morning hours, perhaps thinking about the stake where he was burned on a February morning in 1600. In April of 1943 an uprising, which was doomed to fail from the start, erupted in the Warsaw Ghetto – from behind the walls the people of Warsaw looked on, probably busy with their own lives just as the Romans had been 343 years earlier.

In Rome on the Campo dei Fiori

baskets of olives and lemons,

cobbles spattered with wine

and the wreckage of flowers.

Vendors cover the trestles

with rose-pink fish;

armfuls of dark grapes

heaped on peach-down.

On this same square

they burned Giordano Bruno.

Henchmen kindled the pyre

close-pressed by the mob.

Before the flames had died

the taverns were full again,

baskets of olives and lemons

again on the vendors' shoulders.[1]

...................................................

Czesław Miłosz, Campo di Fiori, Easter 1943

[1] Translated by David Brooks and Louis Iribarne, https://www.poetryfoundation.org/poems/49751/campo-dei-fiori

If you liked this article, you can help us continue to work by supporting the roma-nonpertutti portal concrete — by sharing newsletters and donating even small amounts. They will help us in our further work.

You can make one-time deposits to your account:

Barbara Kokoska

BIGBPLPW 62 1160 2202 0000 0002 3744 2108

or support on a regular basis with Patonite.pl (lower left corner)

Know that we appreciate it very much and thank You !