Benito Mussolini (1883–1945) – successor of emperors; a charismatic and adored leader

The roots of the popularity he enjoyed among Italians, should be sought in the situation, in which Italy had found itself after World War I. The feeling of humiliation inflicted upon the country by the allies, the economic crisis, unemployment in the cities, and conflicts in the backward countryside, all were the background of the more and more often expressed criticism of the conservative government. The slogan of “national renewal” which was put forth into this cauldron of displeasure by the ex-Socialist Benito Mussolini, was quickly picked up. In his statements there was also no shortage of anti-liberal propaganda and overt nationalism. That is why Fascists, whom he represented, easily reached the frustrated and the displeased with their populist slogans.

However, Mussolini’s main slogans concentrated on Italy recovering the power that it deserved and instilling in Italians a feeling of “raising from one’s knees” to which they were forced by the liberal and democratic Europe. Recalling at the same time discipline, authority and patriotism, which had to be built and shaped anew. The purpose was to create a new man on a path of permanent revolution in striving to attain the ideal state. The more and more authoritarian and dictator-like in his actions Duce, became the providential father and chief demiurge of the new order. It should therefore, come as no surprise that, in the name of the aforementioned slogans, at a time of a higher necessity he was able without too much of a problem to suspend freedom of speech for example, it would seem the basic right of any free state. In exchange Italians received a feeling of greatness of the new – third Roman Empire, to which Mussolini felt a successor and creator, while Italians were its continuators. Not solely in the ideological sense either. Instead of a bourgeois (liberal-democratic) handshake, the Roman salute (raising of the hand) was introduced, instead of afternoon promenades –a propaganda spectacle, meaning (in the image of Roman legions), marches of Fascist youth in black shirts, stomping and flexing their muscles on the cobbles of the newly created streets and boulevards. The dictator himself, at the beginning of the thirties stopped wearing a tuxedo and a top hat, exchanging them for uniforms of various color and kind and high boots, underlining (as did in the past Roman armor), the vitality, agility and flexibility of the wearer. In newspapers and films of that time it was possible to see his pictures in which he showed his full body (with a hairy chest – Duce on the beach, while playing tennis, fencing, riding a horse or a motorcycle. The wealthiest women desired to be seduced by him, while gossips of the sexual endeavors of Duce were looked upon with more and more admiration, the more outlandish they were. His vitality was further testified to by five children fathered from a relationship with his wife as well six conceived out of wedlock. Besides an “army” of young girls, who served our hero, his long-time and faithful companion, his mistress Claretta Petacci, who had been in love with him since early youth, was always by his side. As if that was not enough, Mussolini was also a great orator and an excellent actor – with his amusing today but in the past admired gestures he was able to electrify millions of people who were charmed by him. It is therefore obvious, that Hitler himself looked to Duce for inspiration, first having a photo of his idol on his desk and later enthusiastically trying to imitate him, until the time when the student had surpassed the teacher.

What is left after Duce in Rome? Quite a lot. As no other ruler before him, Mussolini in a short time changed the face of the Italian capital from a city of historical monuments, churches and neglected ruins, he created a modern metropolis. Walking around it today, we are not even aware of how often we pass structures or urban arrangements, initiated by a chosen group of architects, sculptors and urban planners desiring to give the capital a modern appearance under the slogan of creating the Third Rome (after the Rome a emperors and Rome of popes). The principal accent was unambiguously placed on recalling the centuries-long tradition of Roman antiquity. And it is from there that Duce began his architectural revolution. Since he styled himself to be a contemporary emperor, the continuator of Octavius Augustus himself (the first in the history of Rome disguised autocrat), it was this time period that he desired to awaken within the city. This was the purpose of “liberating ancient Rome” meaning an enormous cleaning of the city from the remains of the Middle Ages, which within a span of several years to a large extent disappeared from the Roman landscape. In many cases this was urban fabric which developed over time on top of ancient ruins, structures and complexes. For the most part, deteriorated and neglected structures were torn down, in which people lived in primitive hygienic conditions. Displacing them, they were offered better, more civilized living conditions on the outskirts of the city. When we recall the film Bicycle Thieves by Vittorio De Sica from 1948, we will see Mussolini’s new districts – sterile, modern, constructed in empty spaces. Residential construction was an important element of the activities of the Fascist government, a foundation of its success in creating new Rome. A lot was built, while an example that attempts were made to even recall historical styles, and not only the cold functionalism is the Garbatella, created at that time garden district and small, cozy houses, where inhabitants were supposed to feel like in a small town.

At the same time an all-encompassing archeological and urban campaign began. In 1925 Duce announced that “in five years Rome must astonish the peoples of the world. It must appear vast, orderly and powerful as it was in the days of Augustus”. He kept his word. From all across the globe flowed words of admiration for Mussolini’s new Rome. Ancient temples, overtime changed into churches, were restored in all their glory, transferring priests and church property elsewhere (Temple of Hercules, Temple of Portunus). Other churches, for example those found in the area of imperial forums were torn down. A similar fate befell the hospice, chapels and medieval alleys around the Mausoleum of Augustus. The mausoleum cleaned thus, was to become a central point of the newly set out square (Piazza Augusto Imperatore), but also of the whole complex, which included the reconstructed Altar of Peace – a significant work from the times of Emperor Octavius Augustus, which was given a roof and made accessible to the public. On the other side of the Tiber in a similar way, the area around the Castle of the Holy Angel (Castel Sant’Angelo) was arranged as was the Tiberian Island (Isola Tiberina).

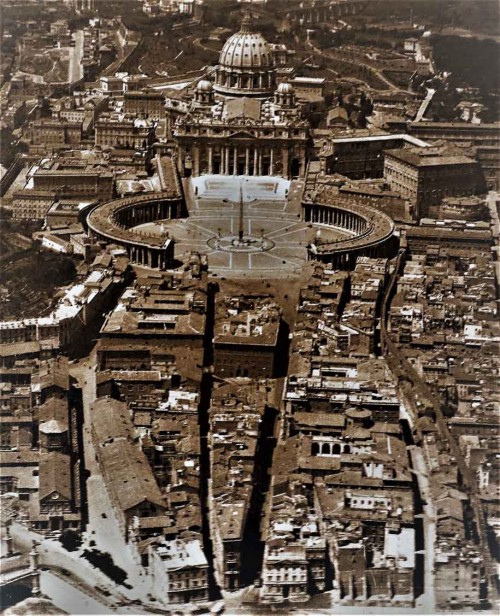

The pace at which the imperial forums and the area around Capitoline Hill were arranged and the temples at Largo di Torre Argentina were uncovered is admirable indeed, but it also meant superficial archeological research and subordinating them to previously agreed upon guidelines. Generally there was not enough time for proper recognition and research. Increased interest in archeology of the era of Mussolini was to serve not so much the deep familiarity with the past, but more so the most intensive preparation of the penetrated regions to present them to the public. The leader searched for roots of the power of the Italian nation, its heroic history, which when shown to Italians, would instill in them a feeling of pride and exceptionality. We can only imagine how much knowledge was buried while setting out the representative boulevard, in a brutal way intersecting the forums, to create the via Fori Imperiali – the representative location used for Fascist marches between the Colosseum and Palazzo Venezia. The area around the Altar of the Fatherland, meaning behind the forums, was a place of special interest for the Fascists due to the Palazzo Venezia located there – the principal residence of Mussolini. It had to be cleared of old buildings, in order to obtain space in front of the palace balcony from which Duce was wont to give his flowery speeches, arousing the enthusiasm and pride of his adorers. It is from this very location that he announced his greatest military success in 1936 – the conquest of Ethiopia – and proclaimed Rome as the capital of a new empire to the great joy of the gathered crowds. Old film chronicles show a crowd of people, standing side by side, filling out the present day Venetian Square (Piazza di Venezia) and cheering below Mussolini’s balcony. From this location, two newly created, imposing in size streets also began, rivaling with the broad roads which were at the same time created in Nazi Germany – the aforementioned via Fori Imperiali and the via del Teatro Marcello stretching all the way down to the Tiber, and further on as via Luigi Petroselli. It is worth taking a look at least at this last one. It is a broad street with raw, brick municipal buildings on either side, only here and there incrusted with travertine. Today they do not attract much attention, and very few people are aware of the fact, that they were created in place of narrow, neglected alleys of old Rome. During the works the area around the Church of San Nicola in Carcere was also arranged, leaving it to stand alone at the edge of the street, the old appearance was restored to two significant ancient structures found at the outlet of the street – the aforementioned Temple of Hercules and the neighboring Temple of Portunus. Another enormous urban development undertaking was setting out the via della Conciliazione (Road of Reconciliation), whose name refers to the great success of Mussolini and Pope Pius XI, namely the agreement which resulted in the signing of the Lateran Accords. Today moving from the Tiber in the direction of St. Peter’s Basilica (San Pietro in Vaticano) and passing the raw structures found there, we generally do not think about the fact that most of them were created in the thirties of the XX century in the location of the densely built-up former “spina”. The inhabitants were transferred to other parts of the city, the buildings were moved or torn town, 600 thousand cubic meters of rubble was taken out. Today it is hard to imagine, that no so long ago this was an area filled with buildings and neglected, but also picturesque and authentically old.

Can we really blame Mussolini, as some have done, that he completely destroyed the medieval fabric of Rome, creating a city of modern, wide streets and representative buildings? We would then in the same way have to criticize popes of the Renaissance and Baroque who in a similarly ruthless way modernized the city, destroying that which had already been in place, without paying any attention to its religious value and even less so to the historical one. Today we call them great constructors and skilled managers of the Eternal City.

Parallel to cleaning Rome, there were plans of completely new urban and architectural undertakings. These were worked upon by traditional architects, but also by the so-called rationalists preferring solutions purist in shape. They practiced their craft at the EUR (Esposizione Universale di Roma) – an ideal city, or more appropriately a district in the south of the city built in a barren area for the World Expo planned here for the year 1942. For Mussolini this was his principal project – giving him the ability to display the achievements of Fascist Italy, in the fields of architecture and city planning. In its modernity and complexity they were to be an example for the whole world, a testimony of the leading role of Rome in art and architecture. This new vision of Rome, a completely contemporary creation, was to be a response to the challenge, which the XX century had placed in front of Rome and its historical sites and narrow buildings – the era of Mussolini. The region with a surface area of 70 hectares was afforested so that the buildings found on an axis with fancy, purist façades and forms found themselves in a seemingly long-existing park. The district, which was to be finished with a modern triumphant arch (The Arch of Water and Light), was connected with the old city center by a broad street, the via Imperiale (present-day via Cristoforo Colombo), as well as by a metro. It should come as no surprise that, the Roman railway station created in the XIX century also needed a new form. The old one was torn down, while in its place the Termini Railway Station was erected with an imposing façade with a length of two kilometers, which was not finished until after the war.

At the same time two significant complexes were created, which were also slightly removed from the city center, providing an opportunity to comprehensively show buildings and decorations in the new style. One was devoted to the cult of the body and sport, the other to the cult of mind and science. The first is of course the Foro Mussolini (currently known as Foro Italico – the sports complex, in which initially the bodies of the Fascist youth were hardened, while later it was expanded at the moment when Italy applied to organize the Summer Olympics. However, a testimony to the fact that Fascist Italy was not only about bodies but also about minds was to be the new university district – Città Universitaria, with the interesting buildings of each individual faculty situated among the greenery.

Romans were also able to enjoy new residential and municipal buildings in Ostia – the popular coastal town, and a getaway destination during hot, summer days, as well as the newly arranged Lido di Ostia, whose semi-circular porticos of the marine and port are ever-present in the proto-surrealist painting of Giorgio de Chirico.

Mussolini was well aware, as were other dictators of the time, of opportunities provided to him by film. The production of films showing the glorious past of the emperors of antiquity was an important, although not the only task of the newly opened film town – Cinecittà.

Today buildings from Fascist times – governmental, municipal, commercial, and all others – can be seen everywhere in Rome. They are just as characteristic for the city as ancient ruins and Baroque churches. They are generally characterized by a raw body, simple elevation surfaces, frequently used travertine (in more costly investments) and brick with elements of travertine in cheaper investments. It is worth taking a look inside as it can be seen just how much importance was placed on their functional but also aesthetic furnishing, in which an important role was played by wooden paneling, metalwork and wall ceramics.

The construction fever was not only prevalent in Rome. In no other state of that time was so much built – city halls, post offices, political bureaus, schools, all popped up like mushrooms in every part of Italy.

It is difficult to list all structures and monuments created in Italy during the reign of Mussolini. Here are a few of them:

- Imposing post offices – at via Marmorata, Piazza Bologna via Taranta

- Romana Ostiense Railway Station

- Ponte Duca d’Aosta Bridge leading onto the Foro Mussolini

- Ponte Flamino Bridge

- via Veneto – Palazzo della Banca Nazionale del Lavoro (National Labor Bank), Palace Hotel

- via Bissolati – National Insurance Institute

- Corso Vittori Emmanuele II – Palazzo dell’INA (residence of the National Insurance Institute) with a relief She-Wolf Feeding Romulus and Remus

- via Regina Elena – building of the National Institute of Health

- via Luigi Petroselli – building of the Department of Development and Infrastructure, on the other side of the street – city hall building and the Registry of Vital Records and Statistics (no. 50)

- Largo Ascianghi (Trastevere) – Casa del Balilla (former building of the Fascist youth organization)

- Janiculum Hill (Gianicolo) – monument to the victims killed in the struggle for Rome in the XIX century (from 1849 to 1870)

Benito Mussolini was born in 1883 in a small town near Predappio in Emilia-Romania in the family of a socialist blacksmith and a teacher. He was also buried there in 1945 after being brutally murdered and hanged upside down along with his loyal until the end mistress Claretta Petacci, in this way ending his 21-year long political career. This town became a true pilgrimage destination for the curious, but most of all for all kinds of Fascists, paying homage to Mussolini under the motto “Believe, Obey, Fight”. Still today many Italians see in Duce the providential father of Italy and do not hide their fascination with this figure. Many of them see the second embodiment of Duce in Silvio Berlusconi.