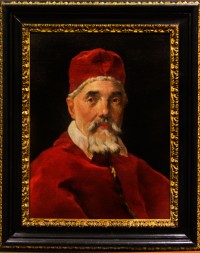

It was most likely as early as his Coronation Mass that the seventy-year-old Pope Leo XI came down with a cold, thanks to which he died after a brief 27-day-long pontificate. His funerary monument completed several decades later was funded by Cardinal Roberto Ubaldini. With this gesture he wanted to immortalize his relative in the Vatican Basilica, however it turned out that this monument was to serve his own, unfulfilled goals.

It was most likely as early as his Coronation Mass that the seventy-year-old Pope Leo XI came down with a cold, thanks to which he died after a brief 27-day-long pontificate. His funerary monument completed several decades later was funded by Cardinal Roberto Ubaldini. With this gesture he wanted to immortalize his relative in the Vatican Basilica, however it turned out that this monument was to serve his own, unfulfilled goals.

Work on the design was entrusted to the famous Roman sculptor – Alessandro Algardi. He created a composition, in which the enthroned, placed on a pedestal pope, turns towards the faithful in gesture of blessing. He is accompanied by to allegories – Liberality (with the meaning of greatness of heart), with a shield and a baton and Magnanimity – with a horn of plenty, out of which coins and jewels pour. The statue itself was completed by Algardi, while the allegories were created by two equally significant Roman artists of the Baroque – Ercole Ferrata (Liberality) and Giuseppe Peroni (Magnanimity) and they are without a doubt some of the most beautiful Baroque sculptures in the whole basilica, similarly to the perfectly made figure of the pope. His hand delicately raised in a gesture of blessing, is to suggest a gentle person, striving for compromise and this was most likely who Alessandro Ottaviano de Medici was – a member of the influential Florentine family, elected as the successor of St. Peter on 1 April, 1605. He enjoyed books, valued art and surrounded himself with noble company (Filippo Neri), supporting reform of the Church in the spirit of the Council of Trent, and on top of that, which was extremely rare, was not a supporter of nepotism.

Algardi is also responsible for the relief adorning the top of the sarcophagus found in the central part of the monument. In selecting motifs the artist did not have a lot to choose from – the pope did not do much of note during his short pontificate (apart from lowering taxes for Romans); he also did not issue any significant decrees. The sculptor could only go back to the time when Leo XI was still a cardinal. Acting as the papal nuncio in France during the pontificate of his predecessor Clement VIII, cardinal de Medici heavily contributed to King Henry IV renouncing Protestantism, and he also took part in peace talks between France and Spain. Both these events were depicted upon the relief. The inscription on the cartouche found among the bas-relief roses placed on the right side of the plinth: Sic florui (Thus I flourished), refers to – obviously – the short pontificate – which quickly “wilted.” The founder of the funerary monument – the nephew of the deceased pope – cardinal Ubaldini did not forget to bring the de Medici coat of arms (six balls) into the foreground, placing it in a decorative cartouche, which seems to be mounted onto the wall of the niche by two flying putti.

We may ask, why did the cardinal wait so long before erecting a funerary monument to his distant uncle. Pope Leo XI had died in 1605, while Ubaldini decided to build the monument 29 years later. And here we enter the arena of political ambitions, conflicts and rivalries with which the then members of the College of Cardinals struggled. Roberto Ubaldini was a member, along with Cardinal Ludovico Ludovisi, of a faction which was against Pope Urban VIII, elected in 1623. They did not accept his pro-French policy, lack of conviction in the struggle against Protestantism and his ever-growing nepotism. When in 1634 the pope fell gravely ill, the cardinals came together in preparation for a possible new conclave, while cardinal Ubaldini – who headed the opposition and was a Spanish sympathizer - saw it as an opportunity for himself. In order to prove his position and rank, he used a very refined form of propaganda, meaning, he commissioned the construction of a funerary monument of his relative. It was not only to recall a de Medici pope, but also make everyone aware of his achievements in European politics, which were based on maintaining balance between France and Spain in international relations. And that is the story the scenes depicted in the relief tell, but also the phrase which appears under the sarcophagus: “He showed more, than he was able to give”, referring of course to the extremely short pontificate, which however was an announcement of peace, harmony and compromise. Most likely cardinal Ubaldini would be an excellent continuator of such politics. The selection of Algardi as the artist of choice to complete the monument was also no accident. He was a rival of the protégée of Urban VII and the Barberini family, Gian Lorenzo Bernini. The “peaceful Baroque” presented by Algardi, which was in direct contrast with the expressive glossary of Bernini’s forms, was to express thought, harmony and seriousness as opposed to drama and exaggeration of the favored at that time Gian Lorenzo. Algardi was the antithesis of all that was presented by his rival, and this can be best seen, comparing the pompous, made in bronze funerary monument of Urban VIII completed by Bernini, with the pope set high on a plinth, with the much lower placed marble statue of Pope Leo XI, who seems friendly, almost human, while the accompanying allegories of virtues can actually be touched as they are within hand’s reach.

However, Pope Urban VIII did not pass away in 1634 as was expected, On the other hand, a year later cardinal Ubaldini died rather unexpectedly. Then works on the statue of Leo XI were halted. It was not finished until 1644, in the same year in which Pope Urban VIII did eventually die.

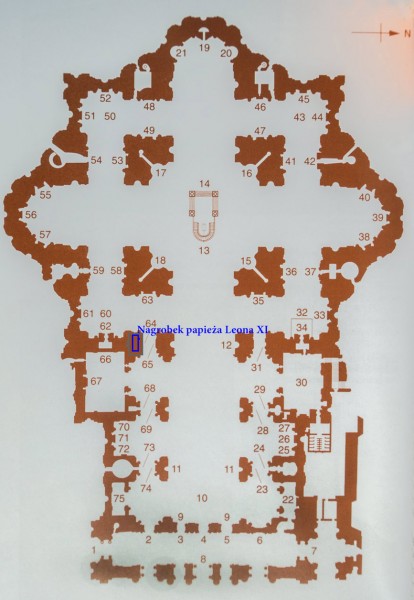

Ultimately the monument was placed on the right side of the passage (on the left) of St. Peter’s Basilica, where its exquisite beauty can still be admired today.