BUDOWLE & OBIEKTY Churches and chapels

Church of Santa Sabina – beauty created out of stone, light and prayer

It was not until the reign of Emperor Octavius Augustus, that with the aim of revitalization of this district, temples were erected here, and then wealthy and dignified Roman aristocrats began settling on the hill with a view of the Tiber, building their impressive villas here.

In Church documents from the V century we will find a mention of “titulus Sabinae”, which means, that the faithful met here for prayers, and it should be added that these meetings were official, without the need for secrecy as was the case in previous centuries. Their hostess, was the wealthy Sabina, a Roman aristocrat and the owner of the building, which probably stood in the same place where the church is presently located. Remains of a house from ancient times were discovered under the main enterance of the church, where remains of a decorative mosaic floor were also found. One of the columns of this structure was preserved in the right nave of the church, next to the Chapel of St. Hyacinth. Unfortunately we do not know much about Sabina herself. Some historians connect her with the influential and wealthy Caecinia family, the same from which St. Marcella came, who gathered around her a group of intellectually and religiously awakened women. Marcella corresponded with St. Jerome, asking him about details of the Bible. She was also the one visited by the latter Father of the Church, during his three-year stay in Rome and she told him of the barbarian invasion on Aventine Hill, of Goths under the leadership of Alaric. Marcella was most likely the aunt of the aforementioned Sabina. It may be hypothetically assumed that his matron, who was twenty-years her senior could have had profound influence on the religious path of Sabina, which was by no means a rule in this family, since its representatives were followers of both the old, pagan beliefs as well as Mithraism. Sabina, was also, most likely the founder of the future structure, devoting, as was often the case at that time, her wealth to achieve this goal. However, a legend connected this location with the martyr – St. Sabina. As we will see this “coming together” into one, of these two persons would come about in subsequent centuries.

The titular presbyter of the church, which gathered at Sabina’s home, was Peter of Illyria (the Dalmatian coast). Apparently, he was also the direct executor of her will, and perhaps also its significant beneficiary or even the heir to the aristocrat’s fortune. This is testified to by a mosaic founding inscription, situated above the enterance to the church, from which we can learn that, the church was funded by – devoting all of his wealth to this cause – Peter of Illyria. Let us take a look at it:

When Celestine had the apostolic summit, and shone out in the whole world as the first bishop, Peter a priest of the City, from the people of Illyria, founded this [church] which you admire, a man worthy of the name at the [second] coming of Christ, who nourished poor people at [his] house, a rich man towards the poor, a poor himself, who fleeing the good things of this present life deserved to hope for the future one.

It must be assumed that the humble presbyter, could not have been the founder of such an impressive building without the financial support of said Sabina. The fact that it was not even the then bishop of Rome (Pope) Celestine I (422-432) can clearly be discerned from the inscription. Most likely it was the first such a monumental, sacral structure in Rome, created without the help of an imperial founder. It held great political significance, which Celestine I is not shy to admit, significantly emphasizing his role in building the church. But there is more. He also underlines, and even manifests his dominant position over the general synod, meaning the other bishops of – Alexandria, Jerusalem, Antioch, and Constantinople, which in those times had to be interpreted as a decisive way to stake his claim to power, while on the other hand giving a signal for a long-lasting policy of the bishops of Rome, who more and more sternly demanded the recognition of the primacy of Rome over other bishoprics.

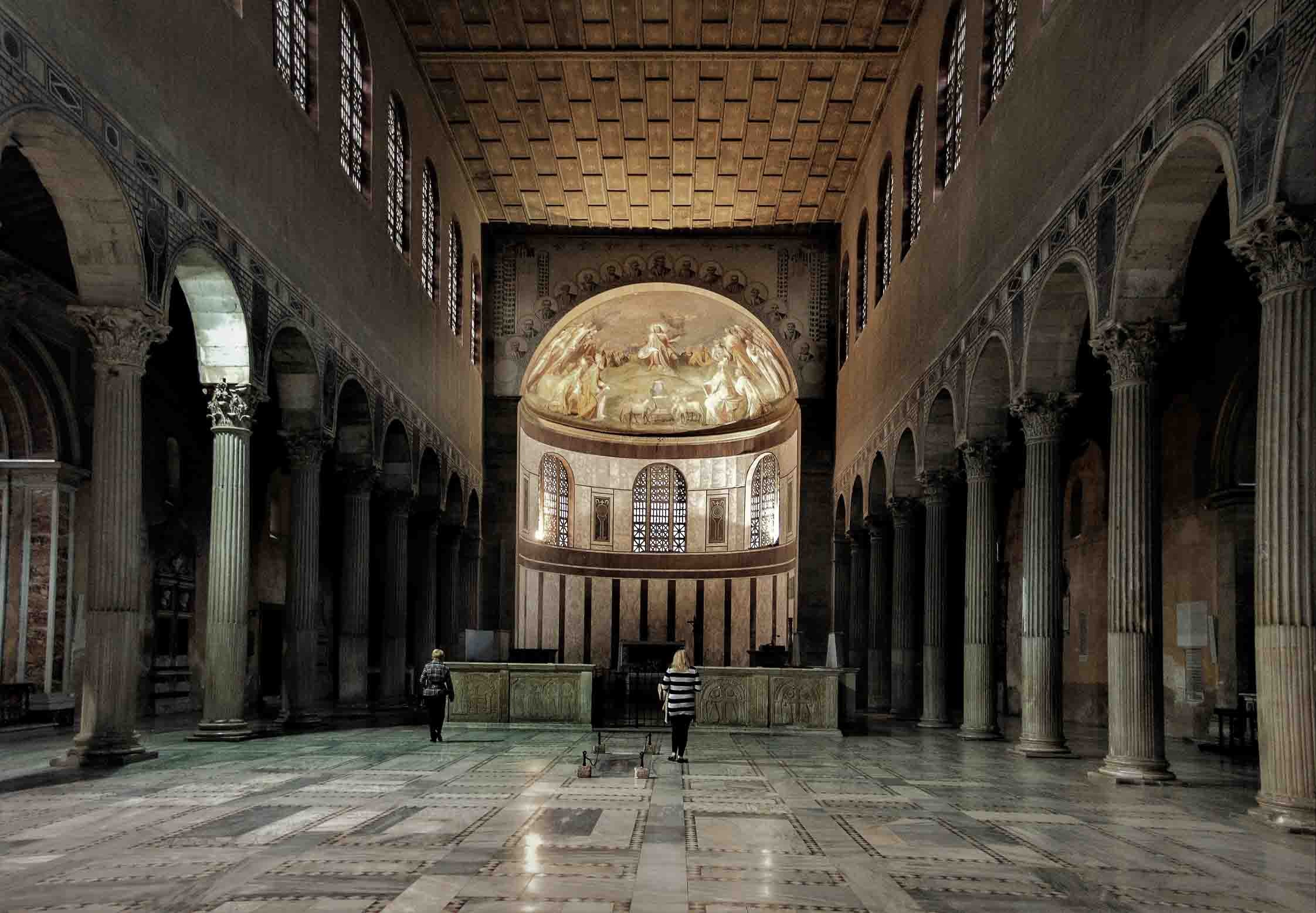

The church erected in the years 422-432, in following centuries was reconstructed and renovated. However, it is an exceptional structure, since having been cleansed of the remains of latter eras during conservational works conducted between 1914 and 1938, it emanates with the spirit of early-Christian architecture. When the bright stream of light pours into the church, through the windows made of selenite, meant to imitate the original ones, its interior almost emanates its pure form. That is perhaps what the original basilicas looked like (San Giovanni in Laterano and San Pietro in Vaticano), of which all trace was lost due to latter modernizations. In Santa Sabina we do not feel this overwhelming monumentality, which characterized the aforementioned churches, since it was created for needs of the commune. The structure was a basilica without a transept (transverse nave), while its finish was an enormous, filled with windows apse, opening onto the whole width of the main nave. Delicate arcades, supported on decorative, fluting columns with refined Corinthian capitols, separate it from the side naves. Historians are uncertain where they come from: until recently it was believed that from the nearby pagan temples of Diana or Minerva, however today it is assumed that, they were created specifically for this very building, which is evidenced by their uniformity, solid execution, as well as the stonemason’s monogram preserved in the shaft of one of them. The side naves, dark and narrow, look like an ambulatory. The windows which presently provide light to them, were not made until the later, Roman period. The wooden, flat ceiling presently covers the roof framework yet as late as the XIX century it was still open. The imposing Cosmatesque floor, created in the XX century, in the image of the one which had existed here in the past, provides additional elegance to the interior.

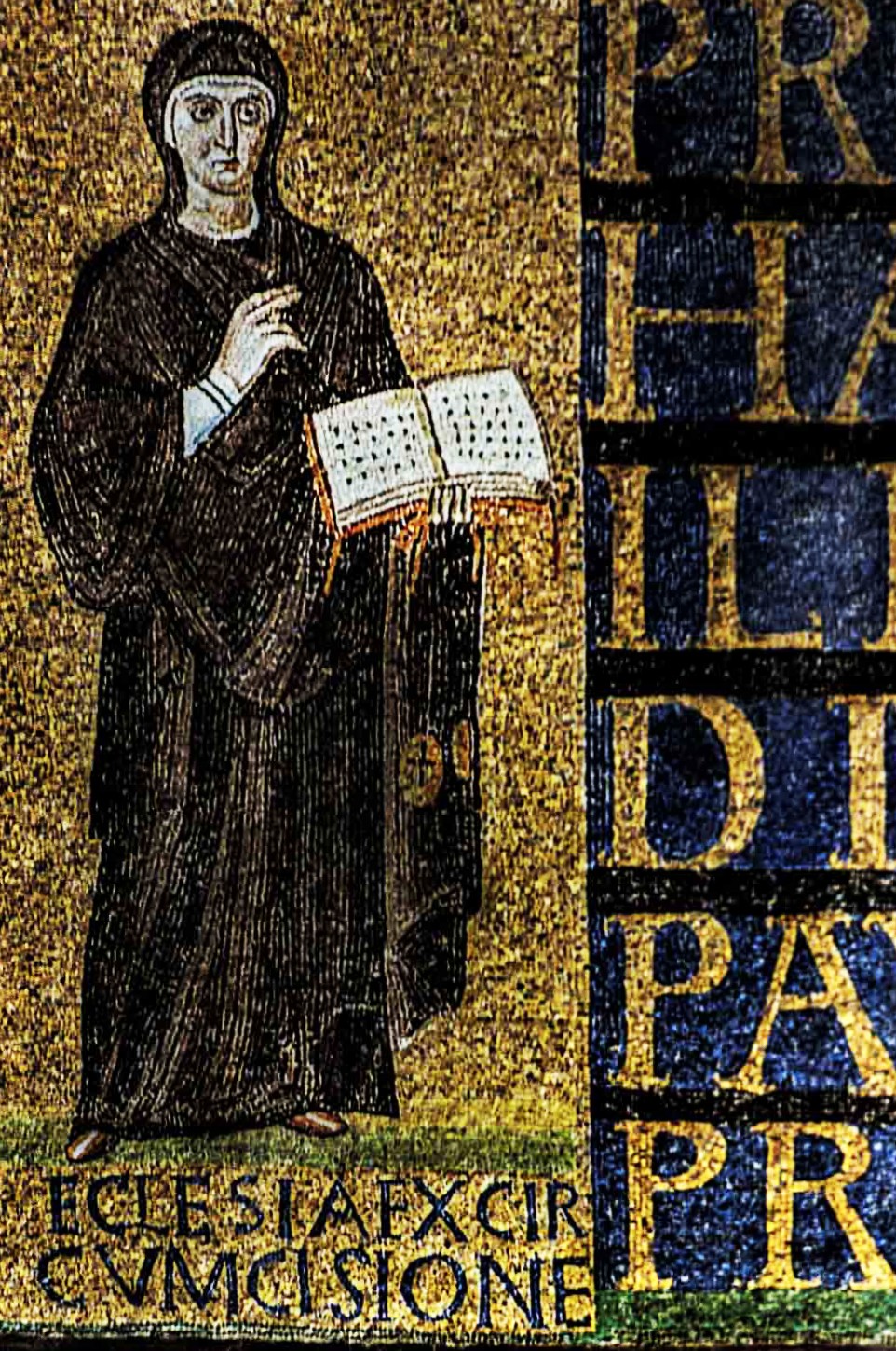

This is a clear, transparent, simple church, seemingly reflecting the faith of people who built it. A frieze with marble incrustations (opus sectile) stretching above the columns and arcades of the main nave, reminds us of the original building. Its upper part consists of geometrical shapes – circles, squares, rectangles, and rhombuses, as well as slabs which imitate bricks, to then display Roman military insignia, enriched by the sign of the cross, which can be understood as the symbol of the victorious faith, in the parts narrowing towards the capitols. In the past the fields among the arcades and windows were decorated with mosaics, which were destroyed during subsequent modernizations of the church. They were also located in the apse. After they were hacked off, the apse part was adorned with frescoes completed by, at that time well-known and valued, but today unfancied painter of the Mannerist period, Taddeo Zuccari. They depict Christ surrounded by the apostles, Fathers of the Church and saints. The drawings depicting the outlines of Jerusalem and Bethlehem in the triumphal arch of the church, as well as images of saints in the medallions are a recollection of the wonderful mosaic decorations. The only remains of the original decorations, are located high on the west wall, in the place of the aforementioned inscription. Barely noticeable, they are some of the oldest Roman mosaics and they show two women who symbolize two Churches – the one, created by converted pagans (Ecclesia ex gentibus) and the Jewish one (Ecclesia ex circumcisione), whose representatives believed in Christ. It is on those two fundaments that the Christian Church was created. One of the women holds the Book of Old Testament the other of the New Testament. They used to be accompanied by figures of SS. Peter and Paul as well as the symbols of the Four Evangelists, but unfortunately they were not preserved.

The church’s greatest treasure is a cypress double door, made specifically for this building around the year 432, a sight which cannot be overlooked by any tourist guide worth his salt, and which in a rather brief summary presents scenes from the Old and New Testament. Out of 28 originals scenes only as few (or as many) as 18 were preserved. The whole is surrounded by stylized ornament of grapevines. These decorations are the work of two craftsmen, very different in their skill and from two distinct artistic traditions. One of them, knew ancient art and used naturalist means of expression with finesse, skillfully modeled figures and used intuitive perspective. The other was a representative of a primitive, almost archaic style, of which an excellent example is an interesting scene found in the left corner, depicting Christ crucified in the company of the two thieves: larger – who set off on the path of penitence and smaller – the impenitent one. Christ however, does not hang on the cross – his figure is displayed with arms outstretched in prayer, with wounds from nails in his hands, and with the outline of a building in the background. This scene is an excellent example of “Pre-crucifixion”, one of the most important iconographic motifs in Christian art. Let us devote a few moments to it.

It is noteworthy that, not only was it presented in a hieratic perspective, elevating the most important people, and thus moving away from the intuitive perspective of ancient Romans, but in addition Christ, who had until then been depicted as a youth, shepherd, or a lawgiver, here for the first time is associated with a martyr’s death, although we do not see the cross itself. This tool of torture, up to that time shown to Christians through abstract symbols, here was connected to Christ, the man, however not yet dead but rather still alive. The artist was not brave enough to kill the Savior, only suggesting his suffering, that was yet to come. It was not until the XI century, when representations of the suffering body of Christ would begin to appear, while in the XII century we will see a truly dying or dead man upon the cross. Another equally interesting scene is the one in the lower right-hand corner of the door, depicting the Old Testament ascension of Elijah, which was a foreshadowing of Christ’s ascension. It was created by a skilled craftsman, creating a vision of an the prophet’s chariot, which his wife attempted to stop in vain.

The object which draws attention in the center of the church is the choir (schola cantorum) completed by Lombard stonemasons between the years 824 and 827, meaning during a period of church modernization – it was reconstructed from various scattered fragments.

In 1221, Pope Honorius III gifted the Church of St. Sabina to Dominic Guzman (St. Dominic) and his friars, asking for a monastery to be built. The Dominican Order still resides within. One of the Fathers of the Church, Thomas Aquinas, also used to live here from time to time.

After leaving the church, on an adjacent square, we are greeted by a stone fountain (Fontana del Mascherone di Santa Sabina), with a fearsome face with bushy eyebrows, a bulging nose, sunken eye sockets and , and an enormous face, out of which a stream of water slowly flows into the marble bowl. This mascherone is quite a bit more charming than his cousin – “the mouth of truth” from the vestibule of the Church of Santa Maria in Cosmedin, yet it is much less admired, despite the fact that its designer was Giacomo della Porta himself.

Before leaving the church, we should linger a few moments in the orange orchard neighboring the church, where from the terrace we can enjoy a breathtaking view of Rome. This place is also known as Parco Savello since in the Middle Ages, the still recognizable tower of the fortress of the Savello family was located here. For many years the remains of these arrangements served the Dominicans as a garden, in which vegetables were grown. This changed during the times of Benito Mussolini. In 1932, the present-day public park with a scenic viewpoint was created. At that time, a roof was put over the orange trees (Parco degli Aranci).

The nightly glow of the city, the winding Tiber at the foot, the illuminated dome of St. Peter’s Basilica, while in the distance the body of the Church of Santa Cecilia on the Trastevere, well visible, and the dominating over the city – striking with its enormity – Altar of the Fatherland, all of these look splendid. The broad apse of the Basilica of Santa Sabina visible from here, towers over everything around, while the lights in the windows of the monastery remind us that, the same Dominicans have lived here for centuries looking on at the Tiber and quietly contemplating the hustle and bustle of the city, from one of the most beautiful places in the world.

In the centuries-old gate of the park there is often a man selling fried chestnuts, whose scent envelopes this location like a balm. When the oranges are in bloom, there is a very different, juicy scent.

Może zainteresuje Cię również

Saint Sabina (Santa Sabina) – an enigmatic saint from the Aventine

Zgodnie z art. 13 ust. 1 i ust. 2 rozporządzenia Parlamentu Europejskiego i Rady (UE) 2016/679 z 27 kwietnia 2016 r. w sprawie ochrony osób fizycznych w związku z przetwarzaniem danych osobowych i w sprawie swobodnego przepływu takich danych oraz uchylenia dyrektywy 95/46/WE (RODO), informujemy, że Administratorem Pani/Pana danych osobowych jest firma: Econ-sk GmbH, Billbrookdeich 103, 22113 Hamburg, Niemcy

Przetwarzanie Pani/Pana danych osobowych będzie się odbywać na podstawie art. 6 RODO i w celu marketingowym Administrator powołuje się na prawnie uzasadniony interes, którym jest zbieranie danych statystycznych i analizowanie ruchu na stronie internetowej. Podanie danych osobowych na stronie internetowej http://roma-nonpertutti.com/ jest dobrowolne.