POSTACIE Roman emperors and their associates

Emperor Caracalla (188–217) – a brutal madman or a victim of propaganda?

Yet, he had all the opportunities to be positively remembered by history. He was given the name Marcus Antonius in honor of being the personification of all virtues of Emperor Marcus Aurelius of whom he considered himself to be a descendant. He himself, was a son of the brave and respected Emperor Septimius Severus and it seemed that since childhood he was marked to be his successor, exhibiting above-average characteristics of a courageous leader. However, history remembers him as a brutal tyrant and a murderer of his own family.

Initial criticism of the young successor to the throne appears as early as the descriptions of episodes from his youth, still during the lifetime of Emperor Septimius. As chronicles state, Caracalla hated his father-in-law – the prefect of the Praetorians Plautianus and his wife married at the age of fourteen Publia Fulvia Pluatilla to such an extent, that he had the former murdered, while the future empress was exiled from the city and imprisoned. After assuming power he had her murdered as well, and removed all traces of her memory. Chroniclers also point out the rivalry between Caracalla and his brother, less than a year his junior, Geta, which increased over time and finally turned into hatred. The ageing Emperor Septimius Severus and his wife Julia Domna unsuccessfully tried to extinguish it. Other words of criticism directed at Caracalla reach our ears at the moment of the illness of the old emperor. The heartless offspring reportedly not only desired his death, but even encouraged doctors and servants to kill the severely ill and suffering father. When he finally died in 211 A.D., Caracalla got rid of his brother, seeing in him a threat to his position of a single ruler. Geta was murdered the same year in front of his mother Julia Domna (as is suggested by chroniclers). Posthumously he was condemned to eternal damnation, damnatio memoriae, which resulted in all inscriptions with his name and all his images being destroyed. Through this act, which went against a certain sanctity, because that is how defiling of kin should be judged, he induced particular discontent of the Senators, moreover because immediately afterwards a true wave of terror was implemented. Caracalla ordered the murder of all of his brother’s supporters, often directing his hatred towards the most important Roman families. All of this did not come to pass without their invigilation and harassment. However, it was not only they, who aroused the emperor’s fury. When Caracalla felt slightly insulted or ignored, he was wont to organize veritable slaughters on the streets of Alexandria or Rome.

He was however, efficiently supported in his actions by a very significant power – a unit of Scythian and German Praetorians, but most of all the army. Caracalla favored soldiers, increased their pay, but was also able to inspire respect and devotion in their hearts. This was all thanks to his soldier nature – the emperor willingly appeared among soldiers, he lacked neither courage nor the ability in battle with the enemy, he was also not afraid to pick up a spade and with all the others dig defensive trenches, if such was the need. He was the type of a companion, who felt right at home among soldiers, but it is impossible to look past his education and refinement. Yet even in his conquests he exhibited far-reaching pride. His conviction about a historic role he was to fulfill can serve as an example, similar to that of Alexander the Great, whose reincarnation Caracalla imagined himself to be at the end of his reign. He desired to create a great empire similar to that of Alexander. Yet the conquests and enormous military expanses were to turn against the empire after Caracalla’s death. In the III century it was power and not abilities that were to play a decisive role in selection of the emperors.

In the memory of the Roman populace, but also later generations, Caracalla will be remembered as the initiator and funder of the largest and most beautiful baths (Baths of Caracalla), of which the likes ancient Rome had never seen before. Undoubtedly in this way he desired to appeal to the inhabitants of the capital of the empire. Another significant act, this time in the political dimension, was the introduction, in 212 A.D., of the Edict of Caracalla (Constitutio Antoniniana), which granted Roman citizenship to all free inhabitants of the empire. His reasons for doing so are somewhat unclear. According to some researchers, Caracalla desired in this way to create new Roman elites, grateful to the emperor for raising their status, in opposition to those who were unfavorably inclined towards him, to others it was a simple economic move, enabling an increase in the inflow of taxes, needed to maintain the army.

It is interesting to take a look at Caracalla’s view of religion, showing a slow departure of emperors from the traditional beliefs of their ancestors. The historian Casius Dio accuses him of superficiality and self-interest in this matter. The emperor reportedly only turned to the deities in times of weakness and illness. Then he gifted all the major deities, but especially Asclepius, Apollo and the Celtic god Grannus. However, he particularly worshipped the popular in Rome since I century. B.C., healer-god – the Egyptian Serapis, for whom he built or more appropriately rebuilt a nearly ruined temple (apart from Serapis, Isis was worshipped there as well), in the Pigna district not far from the present-day Basilica of Santa Maria sopra Minerva. At the end of the VIII century on top of its ruins the Church of Santo Stefano del Cacco, was built, where in the interior twelve of the columns left over from the temple remained intact.

As it turned out, the very thing which was supposed to protect the emperor from death, became its tool. Emperor Caracalla died at the age of 29, murdered by one of his soldiers at Carrhae (present-day Turkey), during the rather unheroic act of urinating. Even today, we do not know why he was killed, since the assassin was immediately murdered. Some researchers suggest, that the reasons was personal dislike and frustration of a simple solider, others, that the person behind the assassination was the prefect of his Praetorians. The Senators were filled with enthusiasm by this act. Since the emperor was childless, his death meant the end of the Severus dynasty. After numerous compromises, the aforementioned prefect of the Praetorians – Macrinus was named emperor.

Caracalla was buried in Hadrian’s Mausoleum (Castle of the Holy Angel), attaining, against the wishes of the Senators, deification during the reign of the following emperor.

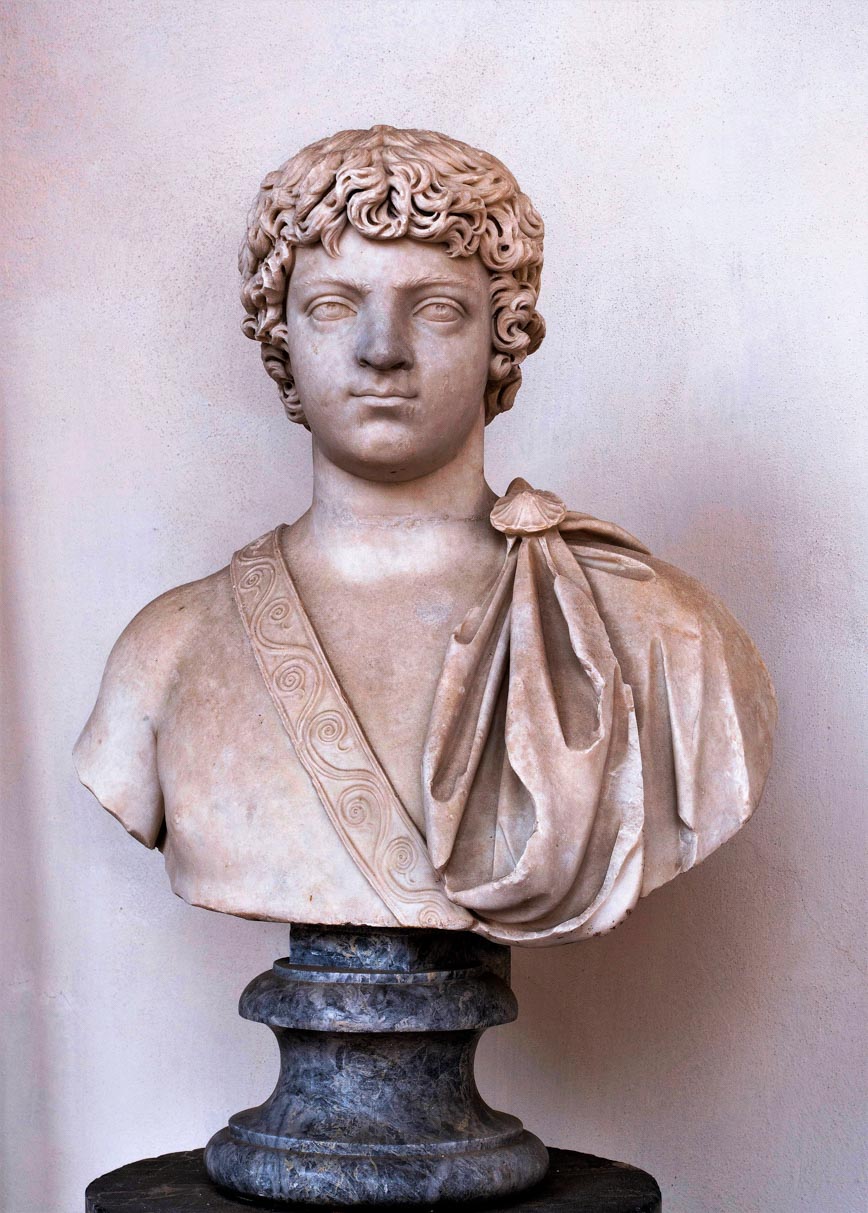

The preserved busts of Caracalla from his youth, show him as a young man of rather noble facial features and curly hair. Most likely this was a rather idealized image, since the images of his brother Geta from the same time period are quite similar. In later times, the emperor already has a beard, while his visage is one of sternness, expressed by a creased forehead and piercing eyes. This way of representing Caracalla was most likely to emphasize his soldierly spirit and unfaltering character. As is stated by Casius, the emperor possessed an almost wild facial expression, while Herodian adds that he was also of sturdy posture. Even in life, Caracalla became the brunt of insults, concerning – as was always the case when somebody was to be insulted – sexual excesses. In this case he was accused of maintaining sexual relations with his mother Julia Domna. Unfavorable opinion of ancient historians, additionally strengthened by the opinion of XIX- and even XX-century researchers, who saw in him a brute, a monster bereft of any human emotions and a madman, in a decisive way influenced the image of this ruler prevalent in popular opinion. While these opinions were not completely unfounded, it must be emphasized that they were highly exaggerated.

The nickname “caracalla” refers to the long hooded cloak which the emperor liked wearing and reportedly personally designed himself in the image of contemporary Celtic cloaks.Może zainteresuje Cię również

Emperor Septimius Severus (145–211) – the one, who made the army into a leading force in the empire

Zgodnie z art. 13 ust. 1 i ust. 2 rozporządzenia Parlamentu Europejskiego i Rady (UE) 2016/679 z 27 kwietnia 2016 r. w sprawie ochrony osób fizycznych w związku z przetwarzaniem danych osobowych i w sprawie swobodnego przepływu takich danych oraz uchylenia dyrektywy 95/46/WE (RODO), informujemy, że Administratorem Pani/Pana danych osobowych jest firma: Econ-sk GmbH, Billbrookdeich 103, 22113 Hamburg, Niemcy

Przetwarzanie Pani/Pana danych osobowych będzie się odbywać na podstawie art. 6 RODO i w celu marketingowym Administrator powołuje się na prawnie uzasadniony interes, którym jest zbieranie danych statystycznych i analizowanie ruchu na stronie internetowej. Podanie danych osobowych na stronie internetowej http://roma-nonpertutti.com/ jest dobrowolne.