POSTACIE Roman emperors and their associates

Empress Julia Domna (150/160? – 217) – an ambitious ruler and an unhappy mother

She was born in Emesa in Syria as the daughter of the High Priest of the Sun God Elagabalus. She came from a wealthy, well-known family, thanks to which she was educated and knowledgeable in literature and philosophy. She met her future husband in 182 A.D. when he was stationed in Syria and was still married to his first wife. When she died, Septimius Severus, as the governor of Galia Lugdunensis, not waiting a long time, by the way of a letter, asked for the hand of Julia in marriage, then, in 187 A.D. the marriage ceremony took place. Legend says that Septimius who believed in prophecies and astrology took Julia to be his wife, because he found out that stars had told her that she would be the wife of a ruler. However, we should just assume that he simply fell in love.

A year after the marriage, in 188 A.D. the first son of Septimius and Julia was born – Caracalla, followed by another a year later – Geta. After the assassination of Emperor Commodus, Septimius Severus – an ambitious and entrepreneurial leader – was proclaimed “Caesar” by his soldiers. He subsequently eliminated his rivals to the title and finally became the emperor of the Roman Empire. His wife received the title of “augusta” and, just as before faithfully accompanied her husband in his numerous, almost never-ending military escapades. The emperor, consciously depicted (on coins, reliefs and inscriptions) her and his successors as an ideal, devoted to Roman tradition family – he, the creator of the new Severus dynasty, and Julia a symbol of harmony and prosperity. Among Julia’s contributions there are numerous, attributed to her renovations of old buildings, which was attested to by inscriptions placed upon them; the Temple of Vesta at Forum Romanum can serve as an example. The qualities of her mind and her interests can further be attested to by the fact that she readily surrounded herself, both in Rome and during her travels, with philosophers and writers, even creating a kind of an intellectual salon.

The ideal image of an imperial family, and especially Julia, suffered due to the calumnies which were spread around the city, by the fearsome prefect of the Praetorians, Plautianus. In order to neutralize his disfavor, for the good of the dynasty, Septimius married off his son Caracalla to the daughter of Plautianus, but this did not alleviate the situation. It was not until the death of his implacable enemy, indirectly caused by Caracalla, that peace returned to the imperial family. However, it was not to last. During a military escapade, which the ill, yet still valiant Septimius carried out to the edges of Northern Europe in 211. A.D., he died. Rulership was transferred into the hands of both sons. They, since long having hated each other, returned to Rome along with their mother.

In subsequent months the conflict between the brothers grew, with the principal issue being, who and how is to rule the empire, while attempts at mutual rule appeared to be impossible to implement. Julia was unable to reconcile her sons, and she was even pulled into a treacherous trap by Caracalla. She arranged a meeting with the aim of final reconciliation. Taking advantage of this opportunity Caracalla ordered his brother to be murdered right in front of their mother, while she herself was wounded during the struggle. After the death of Geta, she was also witness, to Caracalla removing his face and name from all public places, forbidding the conduct of funeral ceremonies in his honor, punishing all those who would mourn him. Moreover, Geta was condemned by his brother to the humiliating act of posthumous oblivion - damnatio memoriae. Julia was also not allowed to mourn and express sadness. At the same time she was honored and worshipped by Caracalla as no other widow or emperor’s mother had been before. She became a symbolic Mother – a protector of the Roman legions, Mother of the Senate, even Mother of the Fatherland. She also had specific tasks to fulfill in her son’s administration, becoming whether she wanted to or not his associate and confidante. A historian of those times who was favorably disposed towards the empress, Cassius Dio believed, that there was great animosity between the mother and the son, while Julia counseled Caracalla reasonably but unsuccessfully. Along with him she went to the east, where Caracalla was preparing for a new war with the Parthians. In Antioch she received the news that her son had been murdered by an anonymous solider but most likely at the order of the prefect of the Praetorians Macrinus. When he became the new emperor initially he showed her respect and offered her the appropriate court and guard. However, Julia ignored his attempts, since she believed he would not gain favor among soldiers, whose devotion to Caracalla she clearly overestimated. She was part of the conspiracy against the new emperor, and alone, ill and harassed she decided to commit suicide: she stopped eating and died of exhaustion in 217 A.D.

Julia Domna’s ashes were initially laid to rest in the Mausoleum of Augustus, later after her sister (Julia Maesa) assumed power, they were transferred to a more representative location – to Hadrian’s Mausoleum (Castle of the Holy Angel), where she was laid to rest next to her husband, Emperor Septimius Severus.

Julia’s contemporary historians spoke positively of her, which however, did not influence her image burdened with the stigma of incest, betrayal of her husband and conspiring against him, which survived for centuries and which started to spread in the IV century along with the creation of the figure of Caracalla as an uncompromising tyrant and monster. It was contributed to by subsequent pagan authors, but most of all by Christian ones, including St. Jerome. Subsequent generations of writers and poets even put Julia in the role of Caracalla’s wife. And despite the fact that starting with the XVIII century all the dark legends surrounding her were looked upon with criticism, while contemporary historians judge her unequivocally positively, her persona is still burdened with a foreboding opinion.

Może zainteresuje Cię również

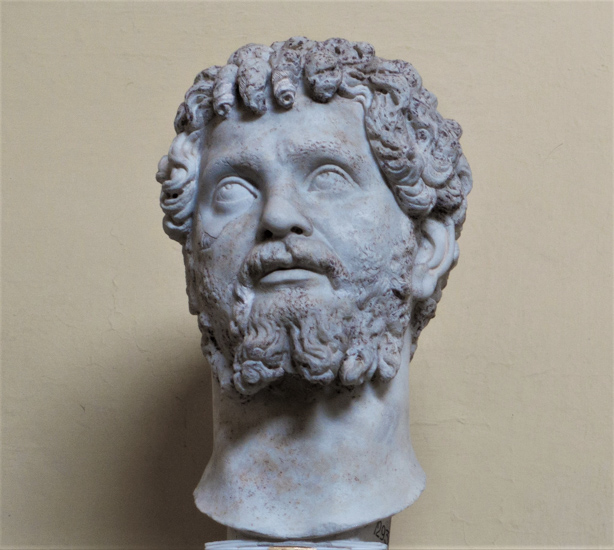

Emperor Caracalla (188–217) – a brutal madman or a victim of propaganda?

Zgodnie z art. 13 ust. 1 i ust. 2 rozporządzenia Parlamentu Europejskiego i Rady (UE) 2016/679 z 27 kwietnia 2016 r. w sprawie ochrony osób fizycznych w związku z przetwarzaniem danych osobowych i w sprawie swobodnego przepływu takich danych oraz uchylenia dyrektywy 95/46/WE (RODO), informujemy, że Administratorem Pani/Pana danych osobowych jest firma: Econ-sk GmbH, Billbrookdeich 103, 22113 Hamburg, Niemcy

Przetwarzanie Pani/Pana danych osobowych będzie się odbywać na podstawie art. 6 RODO i w celu marketingowym Administrator powołuje się na prawnie uzasadniony interes, którym jest zbieranie danych statystycznych i analizowanie ruchu na stronie internetowej. Podanie danych osobowych na stronie internetowej http://roma-nonpertutti.com/ jest dobrowolne.