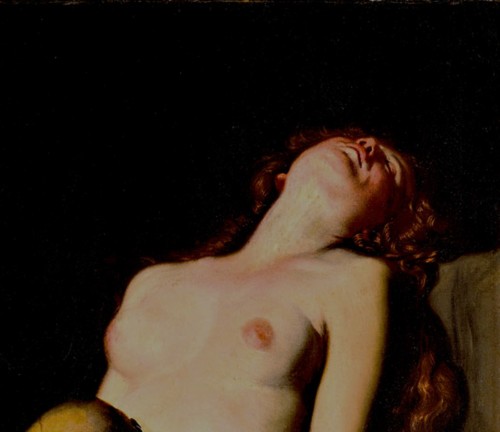

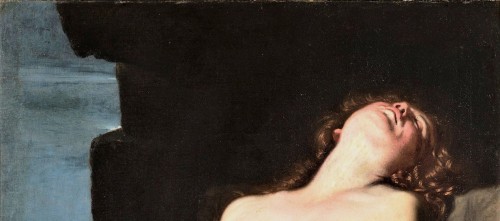

Many artists of the Baroque desired to capture the dualism of the body and soul, while at the same time bringing together into one that which is corporeal with that which is divine, often reaching the border of ambiguity, yet not a single one was able to show this ambivalence as well as Guido Cagnacci, who painted his version of Mary Magdalene. Such a saint had never previously been painted. Her face leaning backward is invisible, while her round breast seems to be directed straight at us and appears to be the central element of the composition. Barely visible is also the cascade of her long hair. The painting emanates eroticism and the sensual power inherent to a woman’s body. And since this power, due to the religious rigorism of those times, could not be expressed in art directly, the figure of the sinful Mary Magdalene, as a painting topic, fit the bill perfectly. Moreso, because the mystical ecstasy, that – according to the legends – the saint had undergone during her stay in the grotto, was quite similar to sexual ecstasy. And we must admit that leaving one’s body and becoming one with the divine element, had never before been shown in a way that was so strongly identifiable with a sexual act.

Who was this woman undergoing ecstasy? In truth, Mary Magdalene was the creation of the mind of Pope Gregory I in the VI century. In his wrong interpretation of the New Testament, he joined into one, three Marys, thus creating a new ideological and intellectual identity named Mary Magdalene – combining together a student of Christ, a sinner, and a converted penitent. In one of his homilies (25), the pope wrote: “ For she, whom sin had first maintained in coldness, love afterwards burned her ardently”. Thus, at the moment of her encounter with Christ, the woman's life was changed while her sinful heart was filled with Divine love. The pope’s words about “burning” added fuel to the fire – right before our eyes appeared a figure full of emotion, inner fire, and sensuality. The corporeality, sensuality, and sinfulness of Magdalene were combined by Pope Gregory I with love and forgiveness and became a cultural mosh-up for centuries to come. The visual arts initially did not use this excessively. The medieval images of Magdalene show her as a static person, in a caul, with an oil vial. However, there is no mention of its significance. Is it the valuable spikenard with which the sinner wiped the feet of Christ in the scene with the pharisee, or is it the one carried by Mary of Magdala to the tomb to – as tradition would have it - anoint the body of her teacher? In time, Mary Magdalene was shown as a woman kissing Christ's feet, despairing at the Cross, while the only sign of her sinfulness was her long, flowing hair (a symbol of womanly charm). It was with this hair that she wiped the feet of Christ or her own tears. It must be added, that in the Jewish culture, but also the Christian culture of the Middle Ages, long, flowing hair was something inadmissible, that was clearly a sign of women of easy virtue.

Images that were a bit more daring in treating the repenting sinner became more common at the end of the XVI century and most likely it was Titian (Mary Magdalene, Palazzo Pitti, Florence), who played a significant and leading role here. He was followed by others, who more and more willingly uncovered the body of Magdalene, covering it only with a cascade of light (generally) or red hair. The fashion for a blond-haired Mary Magdalene was also started by Titian, who felt right at home in the company of Venetian courtesans, who as we know, were wont of brightening their hair. It was already too much to combine the light hair of the courtesans with the Jewish beauty of Magdalene, but this was accepted and readily copied.

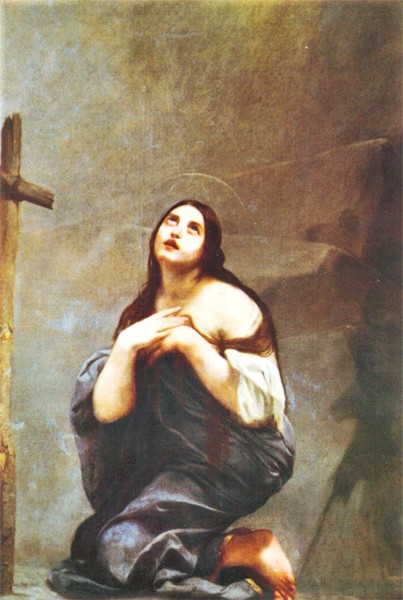

From the end of the XVI century, in images of the saint, next to the oil vial, there are also a skull and a cross, while she herself is placed in a lonely grotto. Other attributes also often include roots, suggesting an ascetic lifestyle of the woman, less frequently a book, and even more seldom discipline. The paradigm of a sinful, repentant Magdalene finally triumphed in the XVII century. Never before, had an image been so charged with sensual allure and eroticism as it had been back then. Generally, semi-nude or scantily clothed she was shown in a state of subtle ecstasy and prayer, with her eyes lifted towards the sky, or in an act of penance and repenting for her sins (see: Penitent Magdalene, Guido Reni, Penitent Mary Magdalene, Charles Mellin).

Keeping that in mind, Cagnacci’s painting seems almost revolutionary. The painter not only chose to forgo the typical iconographic scheme of a woman looking up at the heavens, but he also neglected to show her face, in exchange for confronting us with her semi-nude body. We also do not spy upon her ecstasy but rather observe the moment of physical fainting, already after the mystical climax. We see her burning cheeks and rosy neck, and we can only imagine the effort that she experienced. The metal whip (a tool that serves the taming of impure thoughts and disciplining the body), which she is holding in her hand, would suggest whipping, however, her beautiful body bears no signs of self-inflicted wounds. So is our heroine weakened by whipping herself or ecstasy? And why was the skull – the symbol of the passing of human life – in such an unusual, almost shocking way, placed in the womb of the woman?

Cagnacci’s painting is so interesting because it goes beyond the iconographic canon that was then in place. The way in which the painter combines all the threads – sexual and religious ecstasy, masochism, and penance, and fills them with ambiguity, far exceeds the boundaries of religious adoration. Let us not forget that, the images of the saints, whose cult became widespread after the Council of Trent, were tasked with the strengthening of individual religiousness on the path to salvation. Cagnacci’s canvas, without a doubt, fulfilled another function. It was not meant for adoration, but rather for esthetic pleasure, that many collectors discovered in such bold depictions.

Today, the virtually unknown author of the painting – born in 1601 Guido Cagnacci (Canlassi) – was one of the most famous Italian painters of his time. He created religious works, but most of all study scenes for refined recipients, illustrating erotically uninhibited, scantily-clad, or nude women. After his death in 1663, the painter was forgotten for two subsequent centuries, to be discovered anew, similarly to Caravaggio, at the end of the fifties of the XX century. His dispersed, iconographically daring, and exceptional works, place him among the most unconventional and interesting masters of the paintbrush of the XVII century. Cagnacci amazed not only by the sensuality of his paintings but also by his extraordinary lifestyle. The knowledge of his life comes mainly from police reports and court registers and this information is often the only trace of his artistic journey. The second source is the letters of an eighteenth-century painter from Rimini, Giovanni Battista Costa, drawing an image of an artist who had been essentially completely forgotten by then, but who enjoyed the reputation of a troublemaker. From these letters, we learn about his numerous amorous adventures, in which he continually entangled himself. However, before all that came to pass, he learned painting in Bologna and also visited Rome twice. The painting in question was completed, as it would seem, during his second visit (1621-1622) to the city on the Tiber. He was then only slightly over twenty years old and lived at via dl Babunio (the center of the artistic life of then Rome) along with Guercino. Similarly to other young adepts of painting he admired Caravaggio, but also familiarized himself with the ideas of his colleagues, for example, the detail consciousness of Orazio Borgianni or the realism of Simon Vouet. Undoubtedly, Guercino also had a great influence on him. Most likely Cagnacci was fascinated with the artistic mood of the Eternal City, and its sexual freedom, but he soon departed, occupying himself with his profession. He was active in his native Romagna (a region in northeastern Italy), completing paintings and frescoes that would decorate churches and convents both in small towns (Montegridolfo, Saludecio, Santarcangelo), as well as larger ones (Rimini, Forli, Faenza). In 1628 however, something happened that severely disturbed the pace of the inhabitants of Rimini and also influenced the life of the painter. He was accused of attempting to kidnap and flee with a widow from an aristocratic family, with the aim of marrying her, against both the tradition in place as well as the wishes of her family. The marriage of a craftsman with an aristocrat was at that time unheard of and morally inadmissible. This act caused Cagnacci many problems, court trials, and infamy, which would follow him for ages to come. Denounced by his own father, exiled from the town, and then disinherited, he would from now on look for a place to live in numerous towns. From police reports we learn, that he lived unconventionally – surrounding himself with female assistants dressed as men, and that in 1636 he returned to Rimini, and was accused once again – this time of swindling money out of a woman whom he had seduced. Despite all these problems, both private art enthusiasts, as well as religious orders, continued to seek his services. A particularly interesting example of a work completed for a convent is a painting completed for the Benedictine Sisters of Urbania, depicting Mary Magdalene (1637). As was fit for a devotional painting, the saintly sinner is shown in her traditional apologetic pose, with her eyes directed at the heavens.

In 1640, the painter once again returned to Bologna, where he achieved fame and recognition for his cabinet paintings, designated for private collectors looking for his semi-nude women in half-figure, but also male and female nudes. Undoubtedly, Cagnacci found the appropriate niche for himself in the form of painting with erotic overtones.

Several years later, the artist under the new guise of Guidobaldo Canlassi da Bologna lived in Venice and his works were once again the object of admiration. He established a workshop and successfully painted heroines emanating eroticism – Cleopatra, Lucretia, and Judith, but he enjoyed particular fame due to his paintings of Mary Magdalene. In the City on the Lagoon, the local artists, jealous of his fame, ridiculed his works, which they claimed he painted only to mid-thighs since he could not paint feet. However, nothing could diminish his popularity, just the opposite: in 1660 we can find him in Vienna, as the personal painter of Emperor Leopold I. There he also created one of his most famous paintings – The Death of Cleopatra (Vienna, Kunsthistorisches Museum).

The popularity of Cagnacci's paintings was so great that he himself employed copyists in his workshop, in order to fulfill the needs of his clientele. And its numbers were great indeed. The world of myth, shown in an erotic wrapping and disturbing, sensual beauty, had to make great impressions on the recipients, especially since these canvases amazed with their decisive color scheme, richness of details, and exceptional painting technique. Their author was able to bring forth emotions and use a specific ambiguity – either melancholic or compulsive eroticism.

Today, gradually bringing Cagnacci's paintings out of obscurity we see in them the talent of one of the most interesting painters of the Italian Baroque.

Guido Cagnacci, Magdalene Fainting, 1621, oil on canvas, 63 cm x 72 cm, Galleria Nazionale d'Arte Antica, Palazzo Barberini

If you liked this article, you can help us continue to work by supporting the roma-nonpertutti portal concrete — by sharing newsletters and donating even small amounts. They will help us in our further work.

You can make one-time deposits to your account:

Barbara Kokoska

BIGBPLPW 62 1160 2202 0000 0002 3744 2108 or support on a regular basis with Patonite.pl (lower left corner)

Know that we appreciate it very much and thank You !