The Battle for the Statue of Victory – Rome and the birth of a new religious order

Reconstruction of the Curia at the Roman Forum - the seat of the Roman Senate, pic. Wikipedia

Head of Constantine the Great, preserved part of the colossal statue of the emperor, Musei Capitolini

Bust of Emperor Constantius II, Musei Capitolini

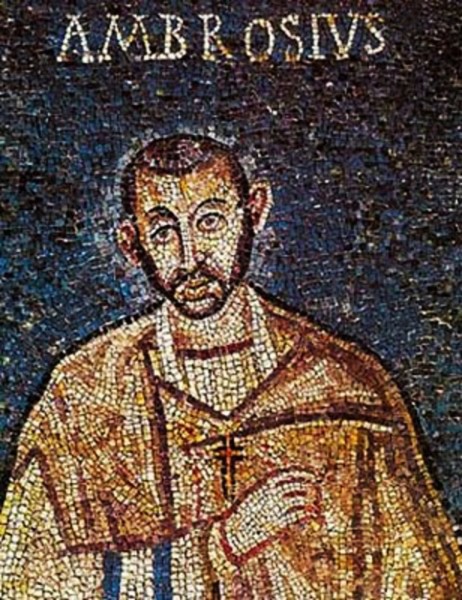

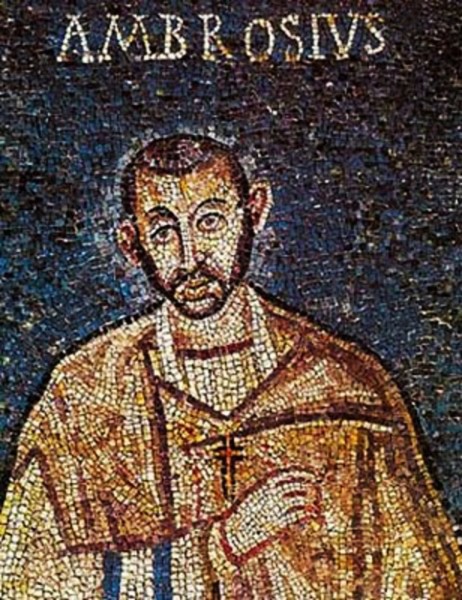

Bishop of Milan Ambrose, early Christian mosaic, Milan, Church of Sant'Ambrogio, pic. Wikipedia

Baptism of Emperor Theodosius I by Bishop Ambrose, Pierre Subleyras, pic.Wikipedia

Bishop Ambrose does not allow Emperor Theodosius to enter Milan Cathedral, Antoon van Dyck, National Gallery, London, pic. Wikipedia

Victoria statue, Parco archeologico di Brescia romana, pic. Wikipedia

Victoria statue, Parco archeologico di Brescia romana, pic. Wikipedia

Apotheosis of Symmachus, part of a diptych, British Museum, London, pic. Wikipedia

It is inconceivable! How could such ideas even come to mind? That was probably the reaction of the Roman senators when they learned that the most sanctified of the symbols of the Eternal City is to be lost, moved, and destroyed. Today it is hard to imagine the heated quarrel that took place between two religious factions and lasted nearly half a century. As a result the policy of religious tolerance which had accompanied the empire for centuries, had suffered an unimaginable defeat at the hands of one religion that did not tolerate any competition. In the history of the city and the empire, a new chapter had begun – Christian Rome.

It is inconceivable! How could such ideas even come to mind? That was probably the reaction of the Roman senators when they learned that the most sanctified of the symbols of the Eternal City is to be lost, moved, and destroyed. Today it is hard to imagine the heated quarrel that took place between two religious factions and lasted nearly half a century. As a result the policy of religious tolerance which had accompanied the empire for centuries, had suffered an unimaginable defeat at the hands of one religion that did not tolerate any competition. In the history of the city and the empire, a new chapter had begun – Christian Rome.

For centuries Romans had believed that multiple religious cults are beneficial, while the prayers for the success of the empire said to individual deities by the representatives of various faiths are what made the empire strong. This pragmatic approach was beneficial for the development of various cults, which were not only tolerated but even supported by the state. The problem was Christians, who did not want to join the ranks of the Roman army and participate in feasts that would worship the emperor, but above all, they did not tolerate other gods. Their lack of interest, when it came to matters of the state and its prosperity, angered other Romans and led to problems and massacres, and often persecutions. This changed after the Edict of Milan, and even more so, when Emperor Constantine the Great, saw in the Christian faith the change to bring together the empire under one emperor and one god. He noticed that Christian tenacity, passionateness, and persistence are a consolidating force for their community, as opposed to polytheistic beliefs, whose energy - dispersed in various cults – was not beneficial towards integration – even if the believers participated in processions and left offerings on the altars ensuring the prosperity of the state and the emperor. Tolerance and disintegration lost in the struggle against emotions and deep religiousness presented by the Christians.

Since the issuance of the Edict of Milan, many years had passed, during which the Christians gradually took over important posts in both the social and political life of Rome. Their numbers grew, but they were still a minority in Rome. Pagans (the followers of the ancient cult) still occupied significant offices and ran the city on the Tiber, while its elites ignored the new religion. The beginning of the conflict between these two religious "factions" was in the year 357 when in the Roman Senate – which had for hundreds of years met in the Curia (Curia Iulia) on the Forum Romanum – someone suggested removing the altar as well as the statue of the winged Victory – the goddess of victory. The senators had to be unpleasantly surprised at the news that, the minority group made up of their Christian colleagues desired to remove this religious symbol. The gilded statue of Victory was not simply an image of some lesser deity, as the Christians referred to the Roman gods, but a symbol of the Empire marked by a long history and tradition.

The statue of the winged Victory with a laurel leaf on her head, holding an olive branch in her hand, came to Rome in the year 272 BC, brought as spoils of war after a victory of the Roman army over Pyrrhus of Epirus (the one from the Pyrrhic victory). However, it acquired particular significance in the year 29 A.D. when Octavian, triumphant in the Battle of Actium ordered it – in thanks for his victory – to be placed in the Senate room. From that moment on every meeting of the Senate was preceded by a ceremony of making an offering on the altar created for Victory – incense, myrrh, and resin were burned on it. And in front of this altar, the senators swore their allegiance to the emperor.

The protest of the senators came to naught: at the order of a declared Christian – Emperor Constantius II (the son of Constantine the Great ) – the statue was removed from the Curia. The emperor died a few years later (361), but prior to his death, he was still able to issue an order to close the temples of the old cults. The following ruler – this time a declared enemy of the Christians – Julius the Apostate ordered the statue to once again be brought into the Curia and the status of the ancient Roman gods to be restored. However, this did not last very long, since Julius ruled for only two years. Current problems caused the statue in the Curia to be forgotten – until the year 383, when Emperor Gratian renounced the title which had been the right of all emperors for centuries, that of the high priest of all religions practiced in the Empire (Pontifex Maximus), and once again ordered the statue of Victory to be removed from the Curia. The senators (representatives of the old religions) decided to take up the struggle for the statute and defend the beliefs which were to be erased from memory. The battle – purely epistolographic, fought with words and arguments – which began at that time was fought between two great erudites of those times. Their task was to convince the emperor of the legitimacy of their arguments. On one side was the senator, consul, and prefect of Rome, Quintus Aurelius Symmachus, proclaiming the idea of the long-standing religious tolerance (polytheism) and respect for the symbols of the past, inseparably connected with the history of the city. In his letters to the emperor he called upon his sensibility, reminding Gratian that it was thanks to the "old" gods that the state enjoyed prosperity and peace. He wrote: “Man's reason moves entirely in the dark; his knowledge of divine influences can be drawn from no better source than from the recollection and the evidences of good fortune received from them.” He argued that turning away from them may bring punishment and the downfall of Rome itself, while breaking the pact with the gods, meaning failing to make sacrifices to them, may turn out to be a tragedy for all Romans.

His adversary, was a great spokesman of those times and a great proponent of Christianity, the later saint – Ambrose, the bishop of Milan. He defended the revealed and only true faith with absolute conviction, proclaiming that only faith in Christ may guarantee the Empire's peace and prosperity. In a response to Symmachus's letters, Ambrose argued that it was not the will of "the old gods”, but the courage of Roman soldiers that led them to victories. Abandoning the old cults and accepting by everyone, the only true religion (Christianity) will ensure Rome with prosperity and protect it from dangers. That is why, according to Ambrose it is impossible to come to a consensus between Christianity and other cults. Both of the speakers came from the Roman elites, represented the same tradition, and shared the same values, what divided them was their view of the place of religion in social life – radical polytheism struggled with an even more radical monotheism.

Ultimately, Ambrose won – Symmachus was not able to convince either Gratian or the following emperor – Valentinian II. The final argument that Ambrose had made, which was to convince the emperor of the need for Christianity to be the only faith is the statement that the statue of Victory similarly to other pagan deities, was a demon.

The statue of Victory once again entered the Curia – although it is worth mentioning that this view is not shared by a significant number of historians – during the reign of the usurper Eugenius, whom the Roman senators supported in exchange for the right to return to the practice of the old cults. But this was a short-lived episode. The year 393 was the last time that the city on the Tiber officially organized traditional celebrations in veneration of the old gods. After the fall of Eugenius, Symmachus once again unsuccessfully tried to convince Emperor Theodosius I to agree to a peaceful coexistence of the old religions with Christianity. The emperor showed mercy towards the supporters of Eugenius, but he did not agree to the practice of any other faiths. The guardian of the emperor’s conscience was the unwavering Ambrose, using the argument of excommunication. As we know, Theodosius is remembered in history as the one who officially recognized Christianity as the religion of the state and who definitely forbade the practice of the old faith; this occurred in the year 391.

Symmachus had lost the battle. The statue of Victory was lost, while he himself died around the year 403.

Only a few years later (410), the Visigoth forces, under the leadership of Alaric ransacked Rome. The myth of the unconquerable heart of the empire fell, while the humiliation and shock felt because of it was the hardest to comprehend for Christians, who believed the Divine state had become real in the shape of the Roman Empire and the cult of their god would guarantee prosperity to the city. The Christians were accused and believed guilty, while pagan Romans saw in Alaric’s invasion a divine punishment for removing the statue of Victory. The later saint, Augustine was terrified at what was happening in Rome. He knew Symmachus – he was his protégée at the imperial court before he fell under the influence of Ambrose and was baptized. The bishop of Hippo deeply moved by the attack on Rome, which he could not comprehend, created one of his most important books: The City of God (De Civitate Dei). He claimed that in this city, the Kingdom of God manifests itself not in some earthly state, but in the faithful who live according to the commandments. In this way, he laid the blame for the sack of Rome on those who did not practice the only true religion and with their profanity, brought about Rome’s misfortune.

And what happened to the statue of Victory? All traces of it have been lost. The only information about its appearance can be gained from the coins on which it appears. However, two other sculptures were preserved, which provide us with a possible image of Victory. One of these is the so-called Winged Victory of Brescia.

If you liked this article, you can help us continue to work by supporting the roma-nonpertutti portal concrete — by sharing newsletters and donating even small amounts. They will help us in our further work.

You can make one-time deposits to your account:

Barbara Kokoska

BIGBPLPW 62 1160 2202 0000 0002 3744 2108 or support on a regular basis with Patonite.pl (lower left corner)

Know that we appreciate it very much and thank You !