The Vestal Virgin Tuccia – between virtue and downfall, meaning the story of an unwanted work

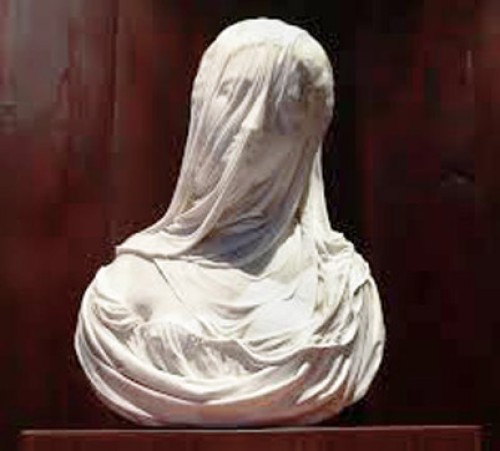

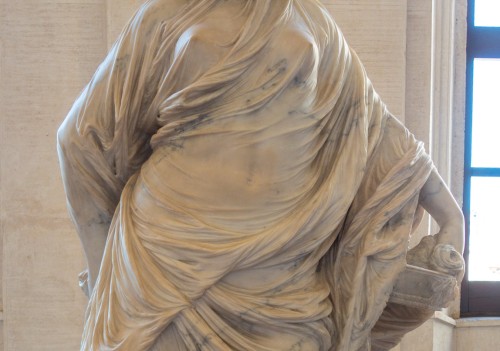

After only several months the sculpture was finished. The delicate, thin veil covers the face and the nude shapely body of a woman with full breasts and a soft belly and in a cascade descends towards her womb. Her face only barely penetrates the veil, as we see the delicate shape of her nose, the outline of the open mouth, and the narrowed eyes. Who is represented in Corradini's sculpture? It is an ancient vestal virgin named Tuccia. Her task (as was the case with all vestals) was protecting and maintaining the eternal fire in the Temple of Vesta on the Forum Romanum. The Vestals, who vowed to maintain virginity, enjoyed particular veneration in ancient Rome. Their virtue and work were of great significance to the state – they guaranteed the proper functioning of the state and military success. The loss of virtue which would be evidenced by the extinguishing of the fire in the temple, prophesized crisis and misfortune for all Romans. When this happened the unquestionable fault of the Vestals was connected with breaking their vows of chastity, which in turn was punished by a cruel death, burying the unworthy priestess alive. It was also believed that only the gods may testify as to their virtue. And this was the case with Tuccia. She was accused of impurity but was allowed to defend herself. She underwent a trial – if she would be able to get water from the Tiber with a sieve, she would prove her innocence. Reportedly Tuccia took the sieve and turned towards her judges. Let us give the floor over to her, recalling Valerius Maximus – a Roman moralizer from I century A.D. and the author of the popular, also during modern times work Nine Books of Memorable Deeds and Sayings ( (Factorum et dictorum memorabilium libri novem), in which he quotes the words of the Vestal: “O Vesta, if I have always brought pure hands to your secret services, make it so now that with this sieve I shall be able to draw water from the Tiber and bring it to your temple”. As the story goes, due to divine intervention Tuccia brought water in the sieve to the Temple of Vesta. From that moment on, the sieve would for centuries be an attribute of virgins and women believed to be virgins. That is why in the hand of the virgin chiseled by Corradini there are a sieve and a rose – symbols of purity and innocence. The veil is an attribute of her tasks. When offers were made on the altar of Vesta and fire was started, the Vestals covered their faces with it. In other situations, as is visible in ancient sculptures, the veil was held up by a band.

In his vision, Corradini referenced a type of a veiled woman, a motif which had in previous years, brought him fame in different parts of Europe. Such statues or busts had been created by the Venetian for the last twenty years, and they had become his calling card. Today we can see them in various locations (La Velata, Museo Ca’Rezzonico, Venice; The Vestal, Skulpturensammlung, Dresden; Faith, Louvre, Paris; The Veiled Woman, Church of S. Giacomo, Udine). This time working in Rome, Corradini wanted to present the Vestal Tuccia, counting upon the fame of his name, as well as a weakness of the Romans towards their own heritage. Tuccia not only symbolized the greatness of the art of antiquity but also had a moral message. The Vestal Virgin was to embody the virtue of purity and innocence, but she was also a true Roman matron, heavily built. In the city of the popes, she could be seen as the prefiguration as well as the post-figuration of Our Lady.

If we were to compare it with Corradini's earlier works, the statue of Tuccia was completed with a much greater, worthy of Rome splendor, in the turgid and monumental style, in which ancient culture intertwines with the Baroque. Corradini also goes a step further in another dimension: the breasts, belly, and belly button made more apparent by the delicate veil, in a conscious way emphasize the eroticism of the woman. The veil does not conceal but rather it reveals that which is underneath, and through this it shows the ambivalent play of Eros with innocence and sanctity. Is the Vestal Virgin really an embodiment of virtue? Does her semi-nude body confirm it, or perhaps deny it?

This ambivalence appealed to the public, which is what the artist wanted most of all. That is because he had to find a buyer by himself and attempt to sell the work which he created with the free market in mind. He came to Rome without any commissions, without invitations, hoping that the fame he enjoyed would be enough to find a purchaser. This was a new, nascent artistic phenomenon, far removed from the way commissions were acquired until then, which was based on completing a specific work, thoroughly described in a contract that was concluded between the buyer and the artist. On one hand, Corradini enjoyed an advantage since he was the one who chose the price, style, and topic of his works, but on the other he had to somehow appeal to an unknown buyer, risking a catastrophe and not being able to sell his work. And this is exactly what happened despite praises in the Roman press (”Dario Ordinario”), which were supposed to attract attention to the sculpture. Another factor, which was to aid in its sale (most likely) was the artist becoming a member of the exclusive and elite group gathered around the Accademia della Arcadia. It was here that Corradini searched for buyers or middlemen to sell his sculpture – all to no avail. The press wrote of the praises coming both from the mouth of the Catholic pretender to the British throne James Stuart and Pope Benedict XIV, and yet the years passed and no offer came.

The sculptor remained in Rome, where he completed small commissions, but after several years had passed he became anxious. He feared that Tuccia would be all but forgotten. Then an idea came to him to show her off to the public in Palazzo Barberini and to sell her during a lottery for a very high price of 400 scudos. The price was agreed upon by a group of his colleagues among which three (out of six) were members of the Arcadia. Despite excellent press and enthusiastic opinions, the sculpture did not find a buyer. Immediately after (in 1748), the irate sculptor left Rome. However, he left Tuccia in the Eternal City, hoping that in the end, a purchaser would appear. As was written by Pier Leone Ghezzi (”Dario Ordinario”), this may not have ultimately come to pass due to the exorbitant price as well as “the jealousy of the lords – Roman sculptors, who did not praise it”. Which “lord sculptors” he had meant, we can only assume. These were most likely the Roman artists who were part of the Academy of St. Luke, who criticized the foreigner and his work. There was too much fabric in it, too much eroticism, and too little dignity and seriousness. Most likely the admiration and fame which their professionally independent colleague enjoyed, going from court to court, also did not gain him any friends.

In Naples, where Corradini went in the spring of 1748 at the invitation of the eccentric Duke Sansovino, he was still attempting to sell the Roman Vestal Virgin, yet his imagination was already occupied by another veiled figure – Prudicizia (Prudence), his most famous work created for the Sansevero Chapel. In it, he used the experience acquired during his work on the Roman Tuccia, but Prudicizia is in her being veiled even more nude, even more erotic, while in the technique and development of the delicate muslin covering her body – even more refined.

The artist died in 1752. The Vestal Virgin Tuccia left in the palace of the Barberini family was not purchased until two centuries later (1952) by the Italian government along with the palace and the art collection found inside.

Today Corradini’s statue is still in the Barberini Palace – it is, in fact, the first work which a visitor encounters coming up to the first floor of the art gallery. And it still amazes and is an evidence of the workshop bravado of its creator.

The Vestal Virgin Tuccia (La velata), Antonio Corradini, 1743–1747, Carrara marble, height: 230 cm, Galleria Nazionale d’Arte Moderna, Palazzo Barberini

If you liked this article, you can help us continue to work by supporting the roma-nonpertutti portal concrete — by sharing newsletters and donating even small amounts. They will help us in our further work.

You can make one-time deposits to your account:

Barbara Kokoska BIGBPLPW 62 1160 2202 0000 0002 3744 2108

or support on a regular basis with Patonite.pl (lower left corner)

Know that we appreciate it very much and thank You !