Funerary monument of Pope Gregory XIII – the memories of the guardian of true faith

Camillo Rusconi, funerary monument of Pope Gregory XIII, fragment, Basilica San Piero in Vaticano

Funerary monument of Pope Gregory XIII Camillo Rusconi, Basilica of San Pietro in Vaticano

Il primo (non conservato) monumento funerario di Papa Gregorio XIII, Prospero Antichi, Basilica of San Pietro in Vaticano

Funerary monument of Pope Gregory XIII, Camillo Rusconi, Basilica San Pietro in Vaticano

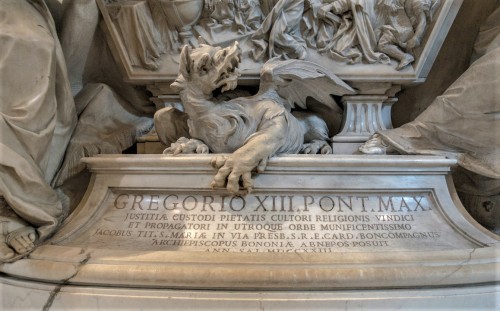

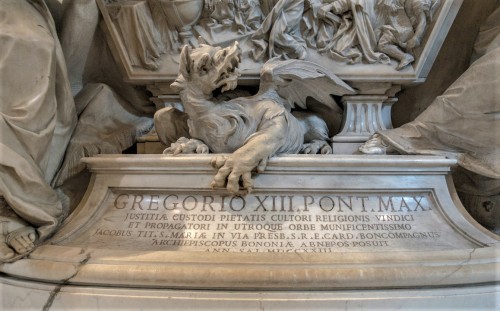

Funerary monument of Pope Gregory XIII, fragment, Camillo Rusconi, Basilica San Pietro in Vaticano

Camillo Rusconi, funerary monument of Pope Gregory XIII, fragment, Basilica San Piero in Vaticano

Funerary monument of Pope Gregory XIII, fragment, Camillo Rusconi, Basilica of San Pietro in Vaticano

Camillo Rusconi, funerary monument of Pope Gregory XIII, fragment, Basilica San Piero in Vaticano

Funerary monument of Pope Gregory XIII, fragment, Camillo Rusconi, Basilica of San Pietro in Vaticano

Camillo Rusconi, funerary monument of Pope Gregory XIII, fragment, Basilica San Piero in Vaticano

Pope Gregory XIII had the foresight to provide for his funerary monument while still alive. In the Basilica of San Pietro in Vaticano, in the right nave (between the third and fourth arch, not far from the chapel funded by him (Cappella Gregoriana) a monument was created consisting of the enthroned figure of the pope and two allegories flanking his sarcophagus – Charity (Caritas) and Peace (Pace). Its little-known author, Prospero Antichi gained renown in Rome thanks to a not quite successful and ridiculed by inhabitants of the Eternal City figure of Moses placed in the center of the dell’Acqua Felice Fountain. This time he was unlucky once again. The pope's monument was completed out of cheap and easy-to-process stucco and was placed inside the basilica in 1585. It was to serve as a model for a future statue, which was to be completed in bronze or marble. However, this never took place.

Pope Gregory XIII had the foresight to provide for his funerary monument while still alive. In the Basilica of San Pietro in Vaticano, in the right nave (between the third and fourth arch, not far from the chapel funded by him (Cappella Gregoriana) a monument was created consisting of the enthroned figure of the pope and two allegories flanking his sarcophagus – Charity (Caritas) and Peace (Pace). Its little-known author, Prospero Antichi gained renown in Rome thanks to a not quite successful and ridiculed by inhabitants of the Eternal City figure of Moses placed in the center of the dell’Acqua Felice Fountain. This time he was unlucky once again. The pope's monument was completed out of cheap and easy-to-process stucco and was placed inside the basilica in 1585. It was to serve as a model for a future statue, which was to be completed in bronze or marble. However, this never took place.

When at the beginning of the XVIII century finishing works on the luxurious and elegant interior of the basilica seemed to be nearing their end, the humble and neglected sarcophagus began to irritate – it was substandard and not representative enough. At the end of 1714, Pope Clement XI informed the cardinal and archbishop of Bologna, Giacomo Boncompagni, that his family should provide for a more representative monument of its ancestor, befitting a pope. Several months later the cardinal gathered a team that was to supervise the works over a brand new monument, which was to be completed by a man who was considered the greatest sculptor of those times in Rome – Camillo Rusconi. The previous stucco monument was removed and the construction of a new funerary monument of Gregory XIII began on the opposite wall, one that would be a response to the new fashion and new challenges.

In a niche above the sarcophagus, we can see the stern visage of the pope with a long beard and a tiara upon his head, as well as his enthroned figure covered with a richly draped robe. The gesture of blessing in which he was captured corresponds to the long tradition of such representations of popes: what is innovative is the fact that due to placing the monument in a narrow passageway this gesture and eyes are directed sideways, which causes us to have the sensation that the pontifex is individually blessing every single person coming from the basilica altar. The allegory of Religion seated at the pope’s feet with a book of the Gospel and a tablet with the Ten Commandments lifts her gaze towards Gregory. On the tablet, we can see an inscription NOVI OPERA EIUS ET FIDEM (I know his works and faith), which is a quote from the Apocalypse of St. John (chapter 2, verse 19). This allegory refers to the significant role of the pope in strengthening Catholicism and its spread. And indeed, the pope was known for his passionate hostility towards the infidels, while the mention of the joy, he was filled with when he received the news of the butchery of thousands of Huguenots on the Night of St. Bartholomew in Paris 1572 became a part of history. A significant act of the struggle against heretics was also the enlargement and modernization of Collegio Romano – a school managed by the Jesuits. The plan of this building, referred to as Gregoriana, from the pope’s name was to be (according to the original sketch) on the shield of the second allegory which is the Magnificence of Rome (Magnificentia Romae), presented with a helmet upon her head. It recalls the splendid, ancient past of the Eternal City but also indicates its heirs, whom the popes considered themselves to be. It is also a reference to a city sanctified by the martyrdom of St. Peter. This very Rome (Roma) – was the center of both the Old and New Worlds, from which the only proper faith came, meaning Roman Catholicism. The figure presented in the allegory leans on a shield with one hand, while with the other she raises the fabric covering the pope’s sarcophagus. Its exterior is decorated by scenes depicting an event with which the pontificate of Gregory was specifically bound. This was the introduction of the new calendar (the so-called Gregorian calendar) and having it replace the one used until then – the Julian calendar. From beneath the sarcophagus, a dragon emerges of course referencing the principal element of the coast of arms of the Boncompagni family, which we will see in all of its splendor in a cartouche at the base of the niche.

The Latin inscription on which the dragon rests its claw praises the pope as a "guardian of justice, adorer of mercy, protector of faith and its promotor in both the Old and New Worlds", further informing us that this monument was created in 1723 by his nephew Giacomo Boncompagni, the titular cardinal of the Church of Santa Maria in Via, and the archbishop of Bologna.

Since Camillo Rusconi was busy with other papal commissions – the completion of the monumental figures of apostles in the interior of the Basilica of San Giovanni in Laterano – the works were halted for a long time. In order to take the load off Rusconi, works on the relief decorating the sarcophagus were entrusted to the Lombard artist Carlo Francesco Mellone, who completed it based on a sketch made by Bernardino Cametti. It depicts the enthroned pope among a group of scholars debating over the aforementioned Gregorian calendar which proved to be quite a logistic and political challenge that turned out to be only partially successful. The Romans of those times joked that the pope stole ten days out of their lives, since in the year 1582, the 15th of October came immediately after October 4th. Roman Catholic countries and a little bit later also Protestant ones implemented the calendar, but the Orthodox Church did not approve it until the XX century.

Ultimately the pope’s funerary monument was completed in 1723. Rusconi was praised for creating a monument giving off the sensation of stability, coherence, and dignity. It was the perfect reflection of the policy of Pope Clement XI, who wanted to accentuate the significance of Rome as the Holy See and the residence of the pope – the warrantor of the only true faith, while his predecessor – Gregory XIII – fit that narrative perfectly.