The Incredulity of St. Thomas– and how strong is your faith?

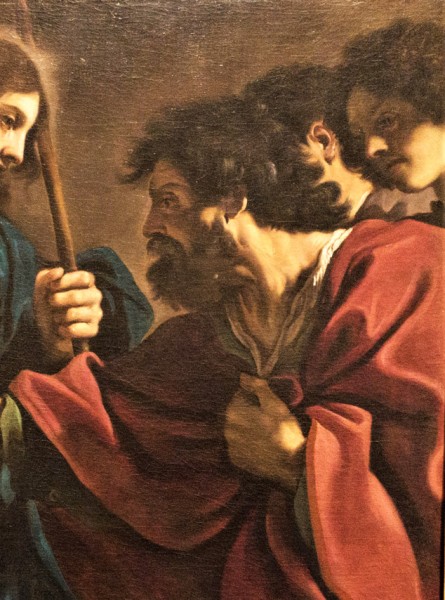

The Incredulity of St. Thomas, Guercino, Pinacoteca Vaticana

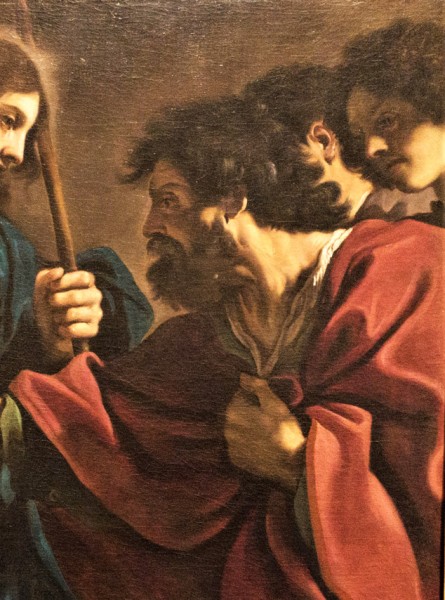

The Incredulity of St. Thomas, fragment, Guercino, Pinacoteca Vaticana

The Incredulity of St. Thomas, fragment, Guercino, Pinacoteca Vaticana

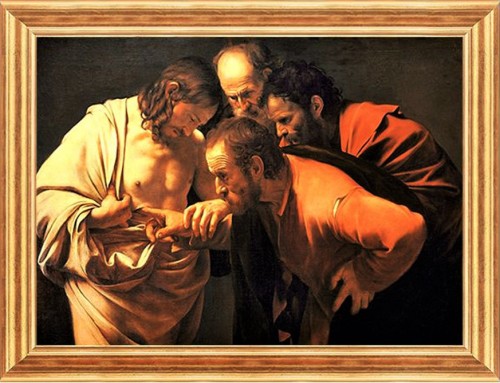

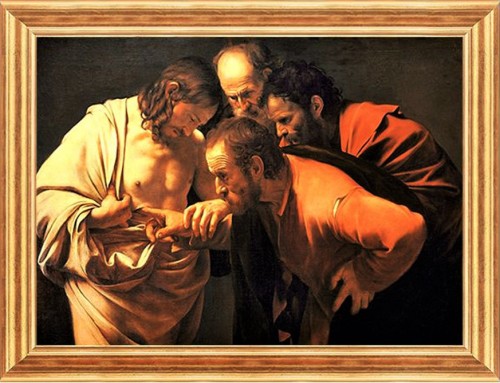

The Incredulity of St. Thomas, Caravaggio, Palais Sanssouci, Potsdam

The Incredulity of St. Thomas, Guercino, National Gallery, London

Hans Dürer, The Incredulity of St. Thomas, Small Passion: 33, British Museum, pic. Wikipedia

The most famous painting depicting doubting Thomas is of course the one painted by Caravaggio, completed by the artist for Marquis Vincenzo Giustiniani, and today located in Potsdam (Sanssouci Picture Gallery). In the past it was the crown jewel of the famous collection amassed by Giustiniani, a work considered outstanding, therefore it should come as no surprise that it was often imitated and interpreted. One of these imitators was Guercino, who took up the subject nearly twenty years after Caravaggio, during his stay in Rome. How did he understand the message of the gospel and how did he treat the meeting between the doubting disciple and God?

The most famous painting depicting doubting Thomas is of course the one painted by Caravaggio, completed by the artist for Marquis Vincenzo Giustiniani, and today located in Potsdam (Sanssouci Picture Gallery). In the past it was the crown jewel of the famous collection amassed by Giustiniani, a work considered outstanding, therefore it should come as no surprise that it was often imitated and interpreted. One of these imitators was Guercino, who took up the subject nearly twenty years after Caravaggio, during his stay in Rome. How did he understand the message of the gospel and how did he treat the meeting between the doubting disciple and God?

Before coming to Rome, the young painter perfected his craft in his homeland of Venice – the painting center of then Europe. There his paintings were enriched by delicate sfumato, refined color arrangement, and brightness of colors, taken from Titian and Tintoretto. He came to the city on the Tiber in 1621, already enjoying the renown of an outstanding painter, adored by Italian aristocrats. He was invited by a well-known patron of the arts, Alessandro Ludovisi, who in the meanwhile took over the papal throne as Gregory XV. During the two years, that he had spent in the Eternal City the artist completed numerous paintings for the pontiff, including frescoes in the Ludovisi residence (casino Ludovisi), as well as the famous The Burial of St. Petronella for the Vatican Basilica. During his stay in Rome Guercino was also able to familiarize himself with the works of Caravaggio, who had died a decade prior. He adopted some of the painting solutions of the master, but his ambitions were much greater. He desired to artistically compete against Merisi, show off his talent in a confrontation with Caravaggio’s work, and nothing could serve this purpose better than the story of the incredulous Thomas. This topic enjoyed great popularity at the beginning of the XVII century, not only due to Caravaggio's canvas. The enthusiasts of the Reformation accused Catholics of believing in saints with fairy tale lives and made-up stories that were not grounded in the gospels. However, the apostle Thomas was a man who did not believe in ghosts. He was a realist, a skeptic, a man who exhibited common sense, and somebody who needed proof that can be seen, but most of all touched (following the motto: first I will see, then I will believe) in order to accept that which others accepted a priori. Therefore, it was not surprising that his meeting with Christ became a popular topic of Catholic art as an attempt to show something which in truth cannot be comprehended – since that is what faith is.

In the Gospel According to St. John, after the resurrection, Jesus appeared to his disciples in the upper room. He showed his wounds and gave them a mission to proclaim the Word of the Lord, then he filled them with the Holy Spirit. Thomas, who was not present when this occurred, did not believe the other apostles, skeptically saying that "I will not believe it unless I see the nail wounds in his hands, put my fingers into them, and place my hand into the wound in his side”. Eight days after, Jesus once again appeared to the apostles and he said to Thomas: “Put your finger here and look at my hands. Put your hand into the wound in my side. Don't be faithless any longer. Believe!" In the Bible, we do not find out whether Thomas actually placed his hand in the wound in Jesus’s side. We are only informed that he said: “My Lord and My God”. Then, Jesus seeing Thomas, who apparently became a believer in his resurrection said: “You believe because you have seen me. Blessed are those who believe without seeing me” (J 20: 24-29).

At this moment we must briefly digress. In Italian art, artists before Caravaggio had painted the scene – In those paintings, Thomas brought his hand close to the Savior’s body but he never touched it. It was presented differently by artists from the North, including Hans Dürer, who was widely respected by artists in northern Italy, for example in Milan, where Caravaggio came from. The artist often referred to his iconography (see: Young Sick Bacchus). Dürer was the one who painted the scene in which Jesus holding Thomas’s hand, almost forces him to place it in his wound. Caravaggio did the same thing in his work. Thomas puts his fingers into the wound below the Savior’s right breast, while he – as if trying to encourage him, holds his wrist – pushing the fingers deeper into his body. Thomas leans and with an effort visible upon his face and wrinkled forehead, looks upon the wound. The two apostles standing in the background do the same. This scene sends shivers down our spine. Caravaggio is very literal and so drastic that we can feel the physicality of the act. Along with Thomas, we move our fingers under Jesus's skin, bend down, and stubbornly look at the wound, becoming witnesses of this incredible event. Thomas's face is filled with boundless shock. The aforementioned two disciples seem less surprised, but just as bewildered, as if they also had wanted to make sure that this person they have seen a few days earlier was not a specter. Christ lowers his head, also becoming in the composition – which is equally as surprising – one of the witnesses to the event. He stands between the apostles, but we do not see his superiority, he is still one of them. There is no holiness in this painting, it is not a meeting of men with God. We can even say that Jesus seems to be curious about that which he took part in – meaning the transformation of man into God. And how did Guercino show it?

Upon his canvas Thomas reluctant and hesitant touches Jesus’s wound, persistently looking upon it. The other apostles take on different approaches. We do not know which apostles these may be. The one with his hands raised (Peter) seems to be saying “I believe without checking” (“who believe without seeing”). However, the second (John?), standing behind Thomas, carefully looks upon his compatriot. Perhaps he too is not quite certain. He believed, but he would like to be assured once again that it was not a hallucination. The third disciple, whose face we cannot see, perhaps does not bother with difficult questions – he believes because the others believe. He would be willing to believe without seeing. In his painting, Guercino shows us very different attitudes regarding belief, that had been attempted by Caravaggio, but at the same time, he poses a question about the strength of our faith. How is it – great or insignificant, constantly put on trial and needing support or perhaps limitless?

And how is the Redeemer presented? Differently than in Caravaggio’s painting. Guercino’s Jesus emanates light emerging from his head in the shape of a pulsating aurora (halo). We can have no doubt that we are dealing with a being out of this world – as Thomas had said: “My Lord, My God". This is further supplemented by the banner (a sign of victory and the symbol of the resurrection), whose shaft Jesus is holding in his hand. His stance is lordly. He uncovers his side, conscious of the miracle that happened through him. And this is what the deeply faithful Guercino shows us – Christ transformed into God, who becomes an object of faith and cult. And that is why Thomas touches the wound, but he is not bold enough to put his fingers deeper into the body of Jesus. He is intimidated by this figure, the brightness emanating from his body, the held-back arm, and the piercing gaze.

Guercino emphasizes the triumphant divinity of Christ, not only by placing him in the center of the composition and surrounding him with a glowing light but also by enriching the painting's color scheme. Because while Caravaggio's painting is almost monochromatic – with dominant dirty whites, bronzes, faded reds, and the white of Jesus’s robes, Guercino instead chooses the highly expensive and greatly valued ultramarine, which ennobles and enriches the whole representation.

Looking at the painting, it is easy to understand the art collectors and patrons who simply adored the works of Guercino. They had panache, decorativeness, elegance, and loftiness, strengthened the faith, all the while arousing strong religious emotions. Along with the painter we are witnesses of a miracle. Guercino not only painted religious scenes, but he also brought the viewer closer to the mystery of faith. In comparison with his painting, Caravaggio's The Incredulity of St. Thomas seems humble and inconspicuous.

Guercino's paintings created in Rome between 1621 and 1623 are considered the best of his works. They combine dignity and distinctiveness with compositional panache, strength of expression, splendor, and refined color scheme. As was customary at that time and being a further testimony to the popularity of the painting and the artist, Guercino painted The Incredulity of St. Thomas at least three times. The first version is found in London (National Gallery), and the second – is the one from the Vatican Museums. The third appeared in 2020 at the Dorotheum auction house and was sold for 100 thousand euros. According to one of the researchers who has studied the work of the painter, Nicholas Turner, the Vatican version – thinly painted with a lot of flair – was the original version less detailed than the later ones.

The Incredulity of St. Thomas, Guercino, 1621, oil on canvas, 120 × 143 cm, Pinacoteca Vaticana