Carlo Saraceni’s Transitus Mariae – meaning how the Discalced Carmelites co-created the image of the Most Holy Virgin

However, before we move on to the painting by Carlo Saraceni found in the Church of Santa Maria della Scala, we must go back in time to the year 1601, when it was commissioned to be painted by the famous at that time Caravaggio. His paintings in the Contarelli Chapel (San Luigi dei Francesi) were admired, he was in the process of finishing other ones in the Church of Santa Maria del Popolo (Cerasi Chapel), while private collectors swamped him with orders. And thus a great admirer of Caravaggio’s talent and a collector of his paintings, Marquis Vincenzo Giustiniani, brokered the signing of a contract between the artist and a lawyer whom he know well by the name of Laerzio Cherubini. The rich, Umbria-born client – a pious man, and a father of four monks – most likely regarded it as an honor to entrust the work to a famous painter. He shared a special bond with the freshly-erected Church of the Santa Maria della Scala on the Trastevere. He was one of the three supervisors of the church (along with Cardinal Benedetto Giustiniani – Vincenzo's brother) and was the caretaker of the Casa Pia – a home for women who were abandoned, thrown out of their homes, or mistreated by their husbands. This place brought together unmarried women – in this way, all of them were protected against prostitution. In 1597, at the behest of Pope Clement VIII, the church was given over to the care of the Discalced Carmelites. Their particular veneration of Our Lady was the reason for the selection of the topic of the painting for the chapel, which was purchased by Cherubini. It was to be a place of masses for the souls of the deceased. In accordance with the contract within a year, Caravaggio was to paint with the "appropriate diligence and care" an altarpiece that would depict the death of the Virgin Mary, or as it was written her "passing”, meaning the state between death and assumption (mortem sive transitium). In the contracts concluded at that time between painter and client, such things as the painting technique, size of the painting, number of figures in the composition, and above all the topic, were all specified. The client generally had a very specific vision of what he wanted to see in the painting. This vision often came about during a conversation with the artist, while more often than not the artist also imposed his own idea and provided sketches. The person taking part in the signing of the contract, someone whom the client could trust, and a person known for their love of art (in this case marquis Giustiniani), was tasked with not only evaluating the artistic value of the painting but also estimating its material value.

The reredos was delivered to the client by Caravaggio and shown to the friars. The Discalced Carmelites were not in fact the direct clients, but it was they who would have the final say as the owners of the church. They rejected the painting. What was it that offended them? Most likely everything. The lifeless body of the Virgin Mary was dressed in a shabby dress, her bloated stomach, a face reminiscent of a recently deceased prostitute and the artist's lover and equally shabbily dressed, barefoot apostles with wrinkle-covered faces. This was an ordinary death, the passing of a simple girl, one that was often seen in shelters for the poor on the Trastevere. The earthliness of this death was overbearing, bereft of loftiness, divinity, and sainthood. Caravaggio could have been disappointed. He did not neglect anything, did not insult anyone, he created a scene that was the expression of the ideas represented not so long ago by Philip of Neri and the Oratorians. One of them, cardinal Baronio, stated that Mary's humanity should not remain hidden, as it was shared with all other women, especially the poor and modest. He was part of a group of theologians, who believed that death is a salvific experience, while the body of the Virgin – a patron of a good death – similarly to her son was mortal. However, the topic of the death of Our Lady turned out to be a much greater problem, one that would provide numerous interpretational possibilities and would divide the theologian community along the lines of misunderstanding and quarrels.

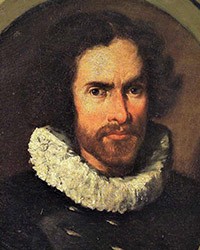

Let us start with the fact that, the New Testament provides no information regarding the death of the Mother of Christ, that is why it can be assumed that Mary died of natural causes and that her tomb can be found in the Valley of Josaphat. This topic only appears in the apocrypha, the so-called Transitus Mariae, of which many had been created since the IV century, but were rejected by the then popes. An example of this can be a decree issued by Pope Gelasius I in 495, which recommended restraint in reading the apocrypha about the assumption of Our Lady and called for common sense. The Church did not want to say anything about the death of the Virgin, as opposed to the authors of the aforementioned apocrypha, who created stories that were willingly read and listened to by the faithful. The basis of all of them was the story that Mary, feeling that death was approaching sent for the apostles. She died without suffering and her body was laid to rest in a tomb. Then Christ appeared accompanied by throngs of angels taking her body and soul to heaven and leaving the tomb empty. Despite the fact that the Church did not approve of the legend, its tradition endured and found its reflection in the Feast of the Dormition of the Mother of God celebrated by the Eastern Church as early as the V century. On the other hand, in the West, the Assumption of Mary (August 15th) became one of the oldest church holidays and became deeply rooted in folk piety. The image of Mary ascending into the heavens among choirs of angels to join the awaiting Christ became a permanent fixture of Western European art. And nobody bothered to ask whether it was her soul or body which escaped from the empty tomb. The Church consequently did not speak on the subject, although within it an argument arose. There was no shortage of theologians claiming that the Virgin had been taken to heaven while still alive, but a similar number denied this possibility. The argument (as it would seem) is still alive today. Seemingly it was put to rest in 1950 in a dogma introduced by Pius XII which states that “the Immaculate Mother of God, the ever Virgin Mary, having completed the course of her earthly life, was assumed body and soul into heaven." However, what does “having completed the course of her earthly life" mean? Caravaggio provided his own answer in painting the deceased Mary. In 1606 the painting rejected by the Carmelites was sold to the Duke of Mantua with the aid of Peter Paul Rubens, who called it a masterpiece. As we can see, artistry does not always go together with the expectations of the people of the Church. Ultimately the canvas came into the possession of Louis IV and today it can be admired in the Parisian Louvre. In the same year, the completion of a new painting was entrusted to Carlo Saraceni. He was at the time a thirty-one-year-old painter. He was a member of Caravaggio's group of rouges and imitated his style but not the iconography itself. He created a composition in which he gave up on the motif of Mary's death. He showed her, while still alive, but ready for

her miraculous assumption, as if in the act of the mysterious passing (transitum) between life and the assumption. As opposed to Caravaggio, Saraceni left out the poignant sadness, and ennobled the scene, while placing the Virgin on a catafalque in a semi-prone position – as if she had still been seated, but was ready to arise. Her youthful face is illuminated by a glowing halo. She is surrounded by apostles – lost in thought or praying, while the whole scene is situated in a room reminiscent of a church interior. As can be seen, Saraceni created a completely new composition, but he took a lot from the work of Caravaggio. The seated in the foreground apostle, lost in thought, replaces Mary Magdalene from the canvas of his master. She, however, also appears in Saraceni's painting but with a covered head and shoulders, she seems to be bowing in front of the Virgin, trying to kiss the hem of her robe. The apostles are wearing sandals (the Discalced Carmelites!), while their physiognomies are free of the marks of poverty, old age, wrinkles, and veins.

However, this painting also did not quite appeal to the friars. This time the problem was the background. Saraceni did not situate his scene in a rundown room, as Caravaggio had done, but rather in a church, which was in his mind to be a reference to Mary as the Mother of the Church. Despite this fact, the reredos was once again rejected. Today the canvas can be found in New York and is a deposit of the Metropolitan Museum of Art.

The next version of the painting was delivered by Saraceni within a few weeks and finally, this one was approved. The slight changes, provide an answer to the question of what was it that did not appeal to the Discalced Carmelites. The Virgin's knees are closer together than in the previous painting. The color scheme of the robes of some apostles was changed. The church interior in the background was replaced with throngs of angels playing music on clouds, which also caused the reredos to be expanded by nearly one and a half meters, in order to create enough room for them. One of the angels seems to be placing a wreath of flowers onto the Virgin's head, another welcomes her, waving a rose branch, while a beam of light appearing in the central part heralds the coming of Christ.

The painting was placed in the chapel. And it must be said that - despite the fact that the painter received a high payment (300 scudos), meaning more than Caravaggio – it was the weakest among all those painted for this interior. The angels completed by Saraceni's students in a definite way separate themselves from the lower scene and are clearly inferior. The artist also allowed himself to play a joke. The face of one of the apostles is the visage of Saraceni himself (central part on the left side), who is looking directly at us as if he had wanted to ask what we think of his work. Or perhaps he was posing this question to the Carmelites themselves? The painting was far removed from the ambitions of its author who ultimately gave in and created a work which the friars had desired and (most likely) their parishioners as well. In their simple, sincere faith, the Virgin Mary after overcoming death "was preserved from the rottenness of the grave, in order to be elevated to the greatest glory in heaven”. This meant, that she experienced neither death, nor resurrection, but while still alive was in a miraculous way taken up to the heavens.

Saraceni's painting was replicated several times in a smaller format. Perhaps the one painted on copper and kept in Venice (Accademia di Belle Arti) was the first version presented to the Carmelites by the painter. It depicts Our Lady – her eyes are closed, her head is leaning forward, palms are resting on her chest. That is probably how Saraceni imagined his painting prior to all the changes and adjustments.

Transitus Mariae, Carlo Saraceni, approx. 1610, oil on canvas, 459 273 cm, Church of Santa Maria della Scala

If you liked this article, you can help us continue to work by supporting the roma-nonpertutti portal concrete — by sharing newsletters and donating even small amounts. They will help us in our further work.

You can make one-time deposits to your account:

Barbara Kokoska

BIGBPLPW 62 1160 2202 0000 0002 3744 2108

or support on a regular basis with Patonite.pl (lower left corner)

Know that we appreciate it very much and thank You !