Rome at the beginning of the XVII was filled with an unmatched artistic ferment, while the city became a center of art. There were several hundred painters active in the city, who came in search of new inspirations, artistic challenges, and commissions, left, stayed a few months and returned. The demand for religious-themed paintings was great while collecting paintings for private contemplation became very fashionable. The art of Caravaggio, enjoyed particular renown at the beginning of the century, as he had a number of admirers, and in time imitators. His fame also reached Utrecht, thanks to the art theoretician and biographer Karel van Mander, who in 1604 when Caravaggio was still alive, wrote about him in his book Schilder-Boeck (The Book of Painters) that: “he creates magnificent things, while his fame is worth highlighting”. Van Mander, also claimed, that every painter must come face to face with the works of this unsurpassed master, and should see the realism of his paintings, the emotions that his protagonists show, and the original manner of the construction of the composition based on strong chiaroscuro contrasts. He even encouraged young painters to go to Rome in order to study and copy his works.

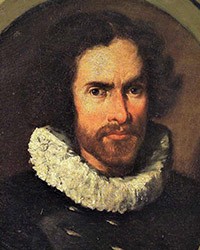

Van Baburen came to the city on the Tiber, most likely around 1617. Caravaggio had been dead for several years, but his fame remained, similarly to his works. The young adept of art had the opportunity to see them in public places (churches), but also in private collections. One of the most-oft praised and admired paintings of the master was The Entombment of Christ found in the Church of Santa Maria della Vallicella. The work shocked with its emotionality and intrigued with the original way in which it approached the topic, but it also inspired many artists to create countless copies, replicas, engravings, and drawings. Van Baburen was also among them, and he had just received a very significant commission – completing the painting decorations of the Pieta Chapel in the Church of San Pietro in Montorio. For a young artist, this had to be a real challenge. His client, was the Spanish diplomat and the representative of the Spanish Kings (Philip III and Philip IV) in Rome, Pietro Cuside (Pietro Cussida) – an art collector and a patron of artists known as Caravaggionists since that is what all painters, who had until the thirties of the XVII century to a greater or lesser extend imitated the grand master, were called.

Van Baburen was to paint three paintings for the chapel, at it must be added that most likely, Cuside initially had wanted to entrust this task to a painter whom he championed and valued greatly – the Spaniard Jusepe de Ribera. However, since his artist of choice had gone to Naples, Cuside had to make do with what he had and entrust the task to his colleague. It is quite possible that Baburen was recommended by Ribera. Both painters were fascinated with Caravaggio but also inspired each other, taking on similar topics in their paintings, and surpassing each other in the use of new solutions and painting means.

The most important task, which van Baburen was faced with was completing the altar reredos with the scene of The Entombment. We do not know whether the idea to reference the famous work of Caravaggio came from the artist or the client. Cuside, as an ambitious art connoisseur, had perhaps wanted to leave behind a significant work of art, equaling the feats of Caravaggio, and he wanted his chapel to be admired by art lovers everywhere. Posthumous chapels served not only the purpose of cultivating the memory of the deceased but were also an expression of the cultural savvy and artistic passions of their owners. Did the young, merely twenty-four-year-old Dutchman, fulfill the expectations of his refined client?

We can imagine him standing in the Church of Santa Maria della Vallicella as he carefully looks upon every detail of Caravaggio’s painting, how he admires the dynamics of the gestures of women filled with pain, and examines the martyred body of Christ, seeing the beam of light reflecting on parts of the bodies and the robes of the presented figures. And finally, we can imagine as he slowly begins to outline his own concept.

However, before we begin analyzing the painting, let us once again recall the aforementioned Karel van Mander. In his opinion, a painter should undergo three stages during his education. The first of these is copying (translatio) of great works, the second is imitatio, meaning the imitation of their style, and the third, and highest is aemulatio, meaning surpassing the original. Most likely van Baburen desired to come face to face with this third challenge. As a result, he created an autonomous work, however, one that was deeply rooted in what Caravaggio gave him. It is an interesting experience to compare both paintings, one which allows us to understand how evolutionary the process of art creation is, and how much it depends on what painters can see and process in an individual way.

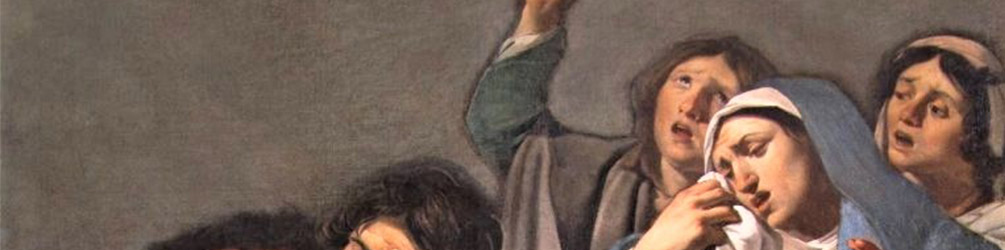

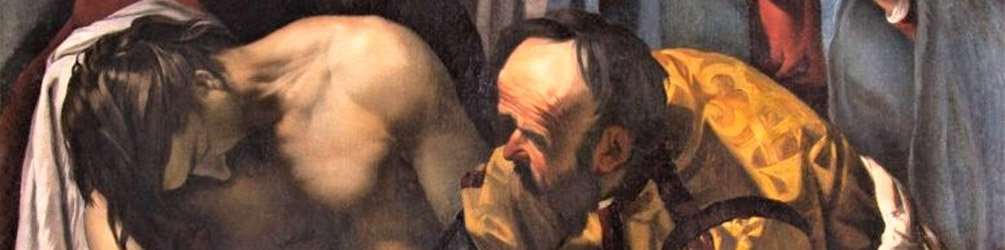

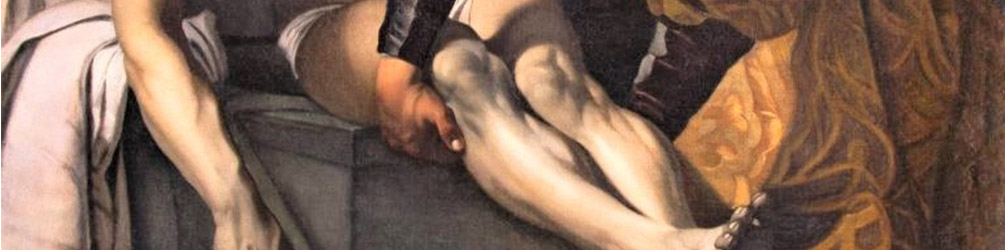

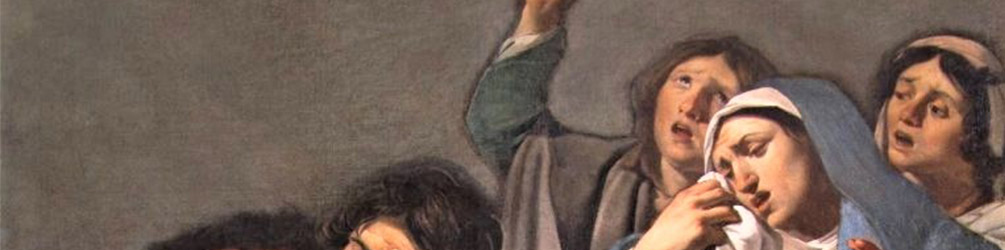

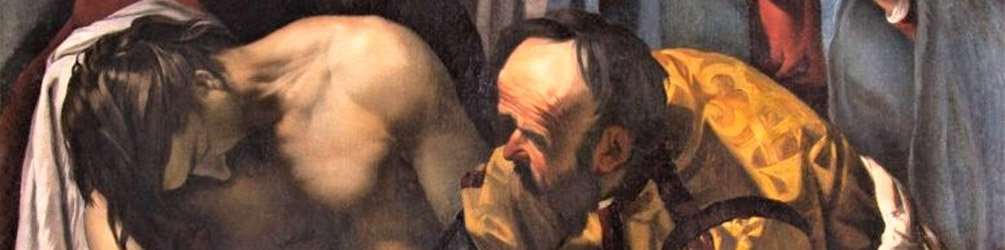

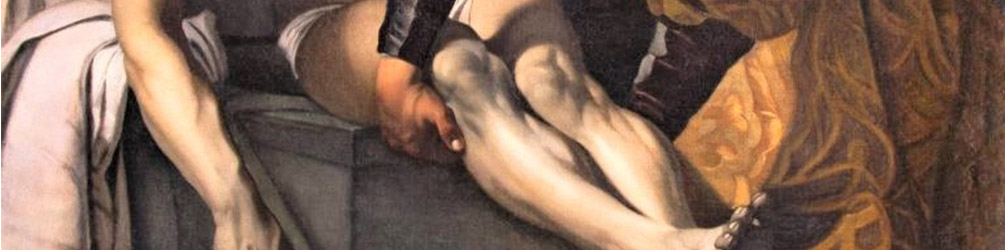

In van Baburen's painting, the figures are situated not on the tombstone (as was the case with Caravaggio) but around the stone tomb, where the body of Christ is being placed. The Dutchman placed it on the edge. Caravaggio shows us the moment of placing the corpse in a grave positioned quite a bit lower, while van Baburen concentrates on the raising of the body as if a second before it would be placed in the grave by St. John and Nicodemus. The body is diagonally placed as if half-seated. We can feel its lifelessness and weight, we see how hard it is for John to hold it up so that it does not slip. The body of Christ, in Caravaggio's painting, is fully lit, in van Baburen's it is in some parts shaded. It is the same with the face of the deceased. The strong light is focused on the bare shoulder of the Savior and the faces of St. John and Nicodemus. The knee of the latter is supporting Christ's heavy legs, while his hands, with great effort, raise his knees. Nicodemus is not looking at us, while his face with a high forehead and deep eye sockets seems to be deformed. The painter seems to be presenting a part of some non-spectacular, almost accidental event happening right in front of our eyes, while we are its equally accidental witnesses. However, that is just the beginning. Among the three Marys, in van Baburen's painting, the main one is Christ's mother wiping away her tears, only behind her, are there Mary Magdalene and Mary of Clopas. A scream seems to escape their open mouths. By presenting this in such a way, the young painter accentuated not the drama and sadness expressed in the gestures of women taking part in the burial, as Caravaggio had done, but the very act of the deposition, in which the women really take on a role of wailers. Behind them stretches a boundless grayness, where there is neither light nor sky.

It is plain, that van Baburen’s canvas is more naturalistic, raw, and less theatrical and decorative than the work of Caravaggio, also in its color scheme. Only the robe of Nicodemus introduces a slight bit of warmth and splendor into the painting. The painting is a complete work it does not shy away from exaggeration, but it also does not avoid ugliness, which is part of human faces. An interesting fact is the placement in the foreground, directly in front of the viewer, an overturned basket with the tools of Christ’s martyrdom. Where Caravaggio places a plant growing out of the grave, van Baburen scatters a hammer, tongs, nails, and the crown of thorns.

The Dutchman’s painting turned out to be an event in the Roman artistic community and brought fame to its creator. It probably also pleased the art collector and client. A testimony to the significance and fascination with van Baburen’s painting is the fact that presently we possess information about twenty-nine of its more or less precise copies, not to mention an equally ample number of drawings and engravings completed based on the painting by various artists in the XVII and XVIII centuries. The number of these artifacts constitutes a huge problem as far as their attribution since at that time painters did not sign their paintings, and this was true for both great painters, as well as second-rate artists. However, this did provide the opportunity for the development of an art market with rather nontransparent (from today's point of view) rules. The border between the original, meaning a work completed with one's own hands by the artist (often based on a written contract) a copy made by the author (an identical painting, completed by the artist in a single or multiple versions) or a copy not completed by the author (completed in the master's workshop, by one of his apprentices or collaborators) was very fluid. The copies (more or less faithful) could have also been created by painters not related at all to the master, who fulfilled the whims of slightly less affluent clients. They were counting upon the fact that impersonating the manner of a well-known artist would be profitable. Imitating and copying were therefore not frowned upon, in fact, it was rather acceptable, which is something that we today cannot understand.

A nearly identical painting to the one created by van Baburen for the Roman church is found in Utrecht (Centraal Museum). It was painted, while still in Rome, for Cuside, this time for his private art gallery, which was to be established in his hometown of Saragossa in Aragon. The collector wanted it to house all the works which he had gathered up to that point, as well as copies of those he had left behind in the Eternal City. However, death put a stop to all his ambitious plans.

The Entombment of Christ, Dirck van Baburen, 1617, oil on canvas, 220 x 140 cm, Pieta Chapel, Church of San Pietro in Montorio

If you liked this article, you can help us continue to work by supporting the roma-nonpertutti portal concrete — by sharing newsletters and donating even small amounts. They will help us in our further work.

You can make one-time deposits to your account:

Barbara Kokoska

BIGBPLPW 62 1160 2202 0000 0002 3744 2108

or support on a regular basis with Patonite.pl (lower left corner)

Know that we appreciate it very much and thank You !