Giovanni Lanfranco’s Venus Playing the Harp – a tribute to music or perhaps to love?

Venus Playing the Harp (Allegory of Music), Giovanni Lanfranco, Galleria Nazionale d'Arte Antica, Palazzo Barberini

Venus Playing the Harp (Allegory of Music), Giovanni Lanfranco, Galleria Nazionale d'Arte Antica, Palazzo Barberini

Venus Playing the Harp (Allegory of Music), fragment, Giovanni Lanfranco, Galleria Nazionale d'Arte Antica, Palazzo Barberini

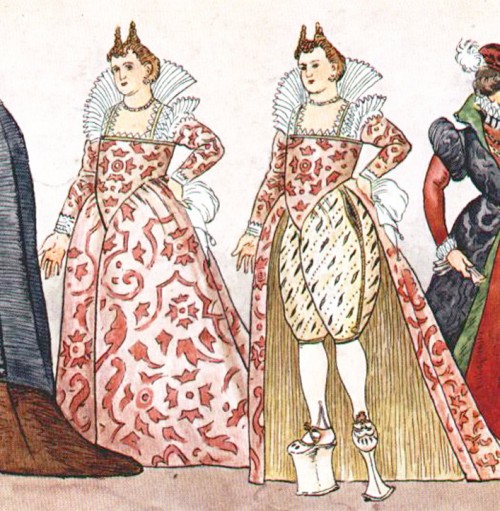

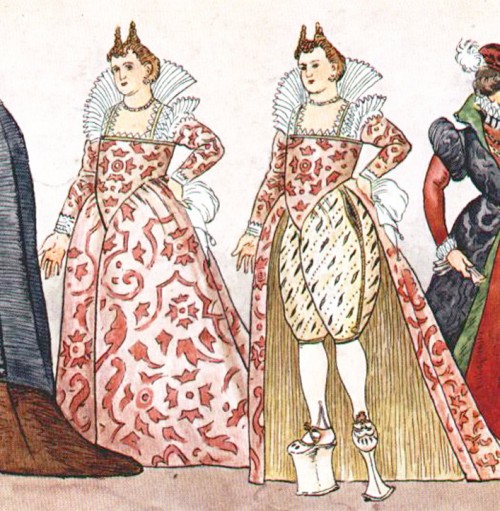

Venetian women, engraving from 1563, pic. Wikipedia

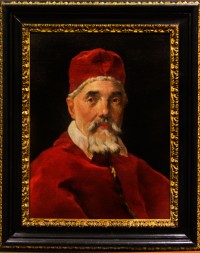

Harp Barberini, Museo Nazionale degli Strumenti Musicali di Roma, pic.Wikipedia

Chopines (Calcagnini), Venice, early 17th century, 27cm x 21cm x 21cm, Galleria Nazionale d'Arte Antica

Venus Listening to Music, Titian, Gemäldegalerie, Berlin

Venus Playing the Harp, Giovanni Lanfranco, Galleria Nazionale d'Arte Antica, Palazzo Barberini

Venus Playing the Harp, fragment, Giovanni Lanfranco, Galleria Nazionale d'Arte Antica, Palazzo Barberini

Venus Playing the Harp, fragment, Giovanni Lanfranco, Galleria Nazionale d'Arte Antica, Palazzo Barberini

Who is the semi-nude woman on the canvas? Is it the allegory of music, or perhaps Venus – the goddess of love, with accompanying, reading the score, amoretti? The scarlet and blue fabrics made of satin covering the woman, and hanging behind her back, seduce the viewer with the soft, wavy, and shiny material. Among these is the woman’s beautiful body, with an enormous harp between her legs. The woman is singing, as her mouth is open, and looks at us in a stubborn manner. Intuitively we feel that this work hides some mystery, an anecdote, or maybe just an intriguing ambiguity. And we are indeed correct.

Who is the semi-nude woman on the canvas? Is it the allegory of music, or perhaps Venus – the goddess of love, with accompanying, reading the score, amoretti? The scarlet and blue fabrics made of satin covering the woman, and hanging behind her back, seduce the viewer with the soft, wavy, and shiny material. Among these is the woman’s beautiful body, with an enormous harp between her legs. The woman is singing, as her mouth is open, and looks at us in a stubborn manner. Intuitively we feel that this work hides some mystery, an anecdote, or maybe just an intriguing ambiguity. And we are indeed correct.

The painting was painted by a well-known, Parma-born painter – Giovanni Lanfranco. In the twenties of the XVII century, this artist was at the height of his popularity in the city on the Tiber. Pope Urban VIII lifted his gaze, to contemplate in awe his frescoes on the dome of the Church of Sant’Andrea della Valle. In the Vatican Basilica, his paintings depicting the Exaltation of the Cross (Cappella del Crocifisso) were admired, while private collectors hired him to paint their rooms. If that was not enough, Lanfranco headed the prestigious Academy of St. Luke. He attained renown, but also significant wealth, which allowed him and his family to live a prosperous life, ensuring comforts and access to cultural goods, typical for the elites of those times. One of these was music. In the aristocratic salons, people met to listen to musicians and singers, while painters and sculptors also tried their hand at playing instruments, and such musical soirees were entertainment of the highest order. At that time, Rome was a veritable mecca of music and not only religious, while members of the Barberini family turned out to be its great patrons. Famous musicians were active in the city (the School of Rome), and in 1626 the Parmigiano clergyman Marco Marazzoli – a singer (tenor), a virtuoso of the harp and in time referred to as “Marco the Harpist” – came to Rome. Soon he became the protégée of the young bon vivant – cardinal and papal nepot Antonio Barberini, but also the papal courtier, composer, the creator of four hundred cantatas and oratorios, and later also the author of ballets and operas, including what is considered to be the oldest comic opera (commedia bufa) – Il Falcone (1637).

Lanfranco most likely met his countryman at the court of the Barberinis and entrusted him with teaching music to one of his daughters. In exchange he was to paint for Marazzoli, who also dabbled in painting, three paintings: Erminia Among the Shepherds, Cleopatra, and a composition depicting Venus with a harp. Therefore, the canvas in question was an expression of Lanfranco’s admiration and gratitude for his daughter’s teacher and master. And what was it for the musician himself? The viewer’s gaze is drawn to an imposing, richly-sculpted, and gilded instrument – an actually existing “Barberini harp”, a new at that time, type of a triple, chromatic harp ordered by Antonio Barberini and completed in 1633 with great piety by the sculptor Giovanni Tubi, in accordance with the drawing of (most likely) Gian Lorenzo Bernini himself. And although the instrument belonged to the cardinal it was entrusted to the musician. Perhaps the scarlet color of the fabric found in the background of the painting is to remind us of this patronage. The then musicologist Giovanni Battista Doni believed that the harp presented not only musical values ideally in tune with the human voice but was "noble, beautiful and graceful in its appearance". In this obvious way, Lanfranco accentuated the status of the musician considered a virtuoso of this instrument, but he also paid homage to the Barberini family, with whom Marazzoli shared a deep bond throughout his entire life. The harp was in his house and returned into the possession of the Barberinis at the moment of his death. Currently it is found in a Roman musical instrument museum (Museo Nazionale degli Strumenti Musicali).

It is clear that this item plays an important role in the painting. However, who is the semi-nude woman playing it? Many saw in her the allegory of music until a testament of Marazzoli was discovered in 1662, in which the painting entitled Venus Playing the Harp Accompanied by two Amoretti was bequeathed to his long-time patron Antonio Barberini. It is worth noting that a representation of Venus playing the harp, in addition to singing was an unusual iconographic motif, which was unknown in the art world. Venus generally only listened to musicians as was depicted by Titian in one of his paintings (Venus and Cupid with an Organist). Interestingly enough, after the death of cardinal Barberini (1671) in the inventory of his collection the painting is entitled Woman of Natural Size, Semi-Nude Playing the Harp by Lanfranco. As can be seen, within a period of barely several years, the heroine of the painting transformed from Venus to a woman. Upon closer inspection, we can see something that the cardinal's family and perhaps even he himself had wanted to keep under the rug. The goddess of love with exquisite earrings in the shape of pearls, with a contemporary hairdo, may have been associated with courtesans who were often portrayed at that time, and who possessed quite a musical education. Frequently they were described and shown with a lute in their hands.

Did then the title referencing Venus have a connection with the land of love and pleasure reserved for the goddess? This is what might be suggested by her bare foot, carelessly placed on a high-platform shoe, which is how Venetian courtesans, who were considered the most beautiful women of those times, were presented. These Venetian women were famous not only in Italy, as the travelers of those times often recalled them in their tales. High-platform shoes appeared in the city on the Lagoon as early as the XVI century. Being worn by elegant Venetian women and courtesans, this underlined their social status, allowing them to better show off their rich robes, made of shining, valuable materials. These so-called chopines also fulfilled a practical function on the muddy and dirty streets. High-platform shoes, generally made of cork and as high as even 50 cm (!) did not allow women to move around normally and it was then that they were aided by servants holding them and the trains of their dresses. Having Venus wear chopines was an indication of showing a more earthly and less allegoric work as any other explanation of introducing this element into the painting simply does not make sense.

The woman is looking at us, drawing us in with her gaze, her song is directed straight at us. Does she want to charm us with a song, or the melody made by the instrument? Or perhaps she wants to show us her power of seduction so often praised by poets? Ever since antiquity, it had been believed that both music and song can arouse strong emotions. And doubtless, these were emotions of love.

Venus Playing the Harp (Allegory of Music), Giovanni Lanfranco, 1633–1634, oil on canvas, 214 × 150 cm, Galleria Nazionale d'Arte Antica, Palazzo Barberini

If you liked this article, you can help us continue to work by supporting the roma-nonpertutti portal concrete — by sharing newsletters and donating even small amounts. They will help us in our further work.

You can make one-time deposits to your account: Barbara Kokoska BIGBPLPW 62 1160 2202 0000 0002 3744 2108 or support on a regular basis with Patonite.pl (lower left corner)

Know that we appreciate it very much and thank You !