Roman coin depicting the Emperor Maxentius

Maxentius as pontifex maximus, Museo archeologico ostiense, Ostia

Maxentius as pontifex maximus, Museo archeologico ostiense, Ostia

Basilica of Maxentius (completed by Emperor Constantine) - Roman Forum

The so-called temple of Romulus and basilica of Maxentius - Roman Forum

Temple of Romulus at the Roman Forum

Basilica of Maxentius at the Roman Forum

Interior of the Maxentius Basilica at the Roman Forum

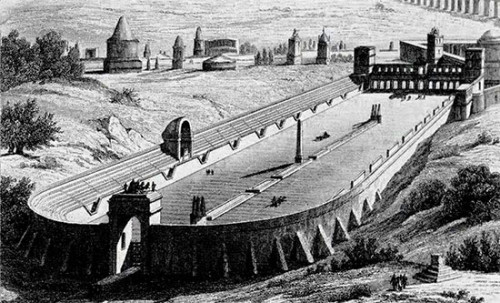

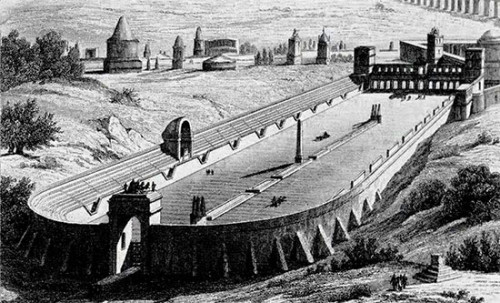

Villa of Maxentius (via Appia) - a palace complex

The mausoleum of Romulus (son of Maxentius) in the complex of the Maxentius villa on via Appia

Emperor Maxentius and the goddess Victoria, Roman coin minted in Ostia from 308-312

Maximian (father of Maxentius), a coin from 286-305

Maxentius, a Roman coin from the time of his reign over Rome

Imperial Regalia of Maxentius, Museo Palatino, pic. Wikipedia

Imperial Regalia of Maxentius, Museo Palatino, pic. Wikipedia

All of those who are interested in Rome, predominantly connect his name with the famous Battle of the Milvian Bridge, in which he lost his life. The fact that he was the rival of Constantine, would for centuries – cloud the perception of his persona. And while his rival, known as Constantine the Great, has become the most important emperor for the Roman Catholic Church, he himself was condemned to damnatio memoriae, acquiring the status of the embodiment of an evildoer. Let us take a look at the propaganda mechanism, which has since the dawn of time accompanied authority and to which Maxentius fell victim.

All of those who are interested in Rome, predominantly connect his name with the famous Battle of the Milvian Bridge, in which he lost his life. The fact that he was the rival of Constantine, would for centuries – cloud the perception of his persona. And while his rival, known as Constantine the Great, has become the most important emperor for the Roman Catholic Church, he himself was condemned to damnatio memoriae, acquiring the status of the embodiment of an evildoer. Let us take a look at the propaganda mechanism, which has since the dawn of time accompanied authority and to which Maxentius fell victim.

Per the wishes of Emperor Diocletian, the Roman Empire at the end of the III century was divided into two parts – Eastern and Western and was ruled by two emperors bearing the title of Augustus, who were aided by two auxiliary emperors with the title of Caesar. The latter were to take the place of the Augusti at the time of their death or abdication. This system of tetrarchy implemented by Diocletian soon turned out to be nothing more than a utopia, while infighting and quarrels among individual emperors quickly highlighted its shortcomings. And thus at the appointment of Diocletian, Maximian (250-310) became the August of the Western Empire, while its Caesar was Constantius Chlorus. After the abdication of Maximian (305), it was Chlorus who briefly assumed the title of August but a year later he suddenly died in Britannia. The armies stationed there, proclaimed his son Constantine as the August, going against the principles of tetrarchy. This fact also encouraged Maxentius (the son of Maximian) to assume authority. Since his relative Constantine could do it, why would he not do it, especially with the opportunity at hand? The residents of Rome were to be burdened with a head tax, which they had not paid until then, so they began to speak out against the lawful ruler of the Western Empire, Severus II. When praetorians came to Maxentius who was residing outside the city, offering him their support, he took advantage of it and proclaimed himself the August of the Western Empire, Lord of Italy, Northern Africa, and a part of Spain in the year 306. His retired father, who was called back to Rome, added to his supporters, especially because he willingly gave out gifts, privileges, and money. The usurper Maxentius settled in Rome and did everything to gain the love and support of its inhabitants. And they could once again feel distinguished and appreciated. In the III century, the city had lost its dominant position in the empire. The emperors no longer resided within its walls and the twenty-nine-year-old Maxentius set out to change this. He settled on Palatine Hill which had been abandoned for decades in the imperial palace thus giving the signal for the return of the emperor to the Eternal City. The foundations initiated by the new ruler were to emphasize his ambitions as the renovator of Rome (conservator urbis) and concerned its center. And so he rebuilt and added splendor to the Temple of Venus and Roma which had been damaged in a fire. Near the Forum Romanum, he began the construction of an enormous basilica (Basilica Nova) designated to house courts and administration. He modernized the adjacent building as well, which is thought by some historians to be the audience hall of the city prefect (the so-called Temple of Romulus). At the initiative of Maxentius, the city walls were strengthened and significantly raised, streets, including the via Appia were restored, as were the aqueducts which were very important for the city. Other this time private foundations can be found in the complex outside the city walls at via Appia.

Maxentius began his reign by restoring the cult of the traditional gods and Roman heroes, especially Mars and Hercules. However, he did not persecute other religions, but rather he was a ruler who treated each religious group with tolerance, before the signing of the famous Edict of Milan. In this way, he continued the policy of Emperor Galerius, trying to integrate the community under a common banner, meaning the good of the empire, and its residents of different religions. He allowed the Christians to once again freely choose their bishop and returned the properties which had been taken away in the past, which is mentioned by St. Augustine. The fact that some historians, for example, an expert of those time Elżbieta Jastrzębowska, point to Maxentius as the founder of the first early-Christian structure (Basilica Apostolorum) at via Appia (present-day Church of San Sebastiano) would even prove that his policy towards Christians was more than friendly.

At that time the relations between Maxentius and Constantine were quite good, which is further testified to by the latter marrying the stepsister of Maxentius, Fausta (307). Both were young, ambitious, and shared a common enemy – the Augustus senior, Galerius. The position of Maxentius was threatened for a moment when his own father attempted to dethrone him. However, the praetorians and the army took the side of the young emperor and Maximian had to flee from the city, looking for help from his son-in-law Constantine in Gaul. There he died under mysterious circumstances, to which the son-in-law probably contributed. The relations between Maxentius and Constantine worsened when the latter decided to rule the West himself. Ultimately both the usurpers met near the Milvian Bridge, in order to fight the decisive battle. As we know, Constantine emerged as the victor. He had the body of his brother-in-law and recent ally quartered, while his head was placed upon a spear and triumphantly carried into Rome, giving a clear signal as to what could happen to the supporters of Maxentius. The praetorians who were faithful to him, and who survived the battle were killed, while the formation itself was disbanded, taking away all its wealth, which was then to a large extent given over to Christians.

Constantine’s victory in the brotherly struggle, which Romans could not have been proud of in subsequent centuries, had to be transformed into glory by his supporters. It was necessary to insult Maxentius in every possible way. It was thus proclaimed that he was a tyrant and a usurper, he was subject to damnatio memoriae, meaning that his memory was condemned but even that was not enough. Maxentius's mother, Eutropia was forced to admit, that his son was not the son of Maximian. In this way, Constantine was able to rehabilitate and deify his father-in-law, which of course was done to serve his own propaganda aims. At that time, Maxentius had not yet been accused of being an enemy of Christians, but in later sources, he would be presented as their persecutor. It was not only Constantine but all chroniclers of the upcoming times, who would desire to wipe all traces of this ruler, at the same time creating his black legend.

A great fervor among historians was caused by the discovery of Maxentius's imperial insignia on Palatine Hill in 2005. Perhaps they had been buried by his allies in order not to fall into the hands of Constantine and lay hidden underground for one thousand seven hundred years and they are the only original example of imperial insignia which had survived until the present.

There is yet another historical monument that remained from the times of Maxentius, and it can be seen in the courtyard of the Capitoline Museums (Palazzo dei Conservatori). It is, the nearly thirteen-meter tall statue of the seated ruler, whose remains (foot, head, finger, and shoulder) are kept here, and which is considered to be the image of Constantine the Great. It was created to adorn the apse of the Basilica Nova, and initially represented Maxentius, the last emperor who not only resided in the city but desired to bring back its splendor and significance. After his death, the figure (or more appropriately the head) was transformed into the image of his enemy – Constantine. And thus it was not only Maxentius's good name and merits that were "stolen", but also his statue which today is unanimously identified with Constantine.

The foundations of Maxentius in Rome:

- The Basilica of Maxentius (Basilica Nova) next to the Forum Romanum along with a 13-meter statue of Maxentius

- The Villa of Maxentius – a complex of buildings at via Appia Antica (the Mausoleum of Romulus, hippodrome, summer palace),

- Basilica Apostolorum at via Appia (attributed to him)

In 312, Rome was magnificent indeed, it shone with white marble, gleamed with the gold of its statues, and impressed with order and splendor. This can be seen in the reconstruction of the city, available online (youtu.be/fNIEYmxFgF4). Never again, would it be so grand and well-cared for. Although it had not been the capital of the empire for a while back then, it was still its heart, which along with the death of Maxentius stopped beating with its imperial rhythm. Constantine dealt it a final blow at the moment of transferring the political center of his state to Constantinople.