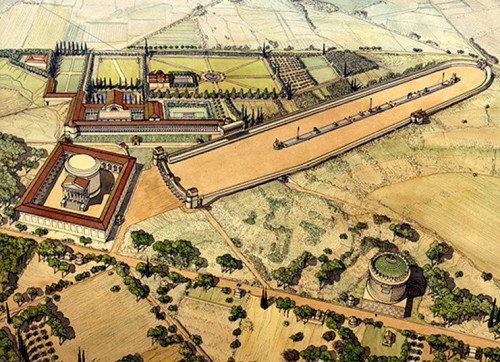

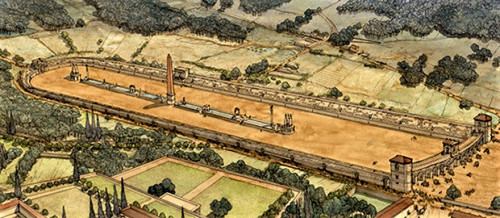

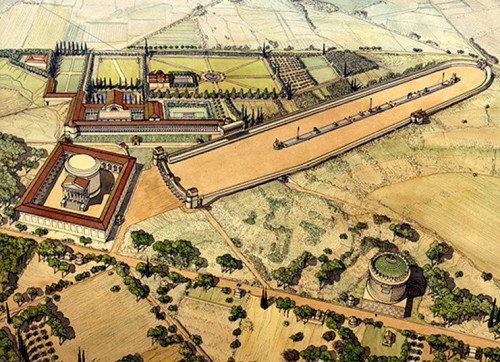

The Villa Maxentius at via Appia, reconstruction, pic. Wikipedia

Remains of the Romulus mausoleum with an added building in the modern times

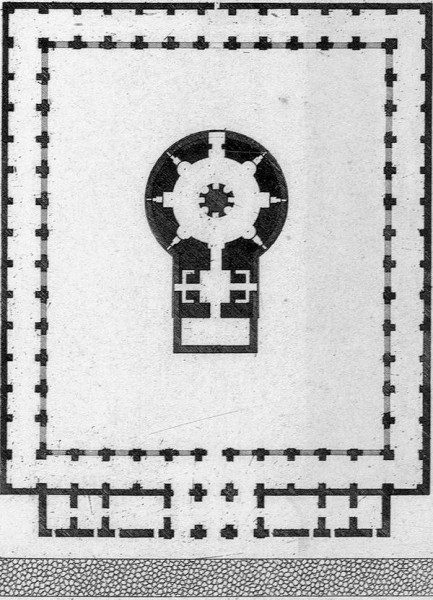

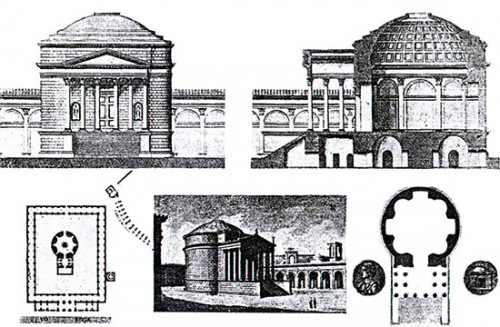

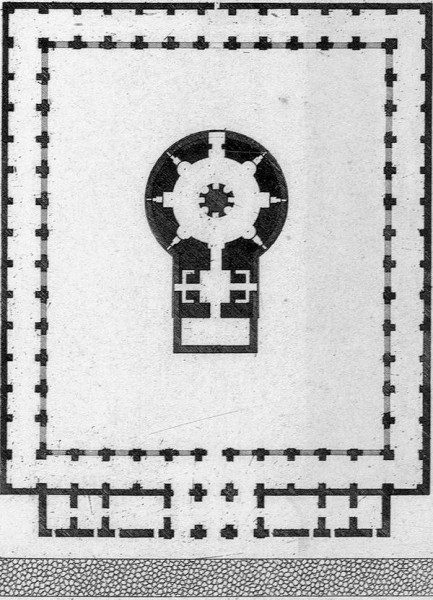

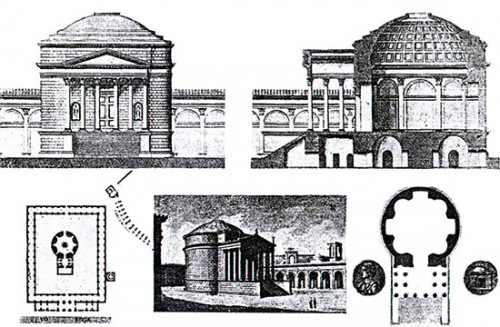

The Mausoleum of Romulus (plan) in the complex of the Maxentius villa on via Appia

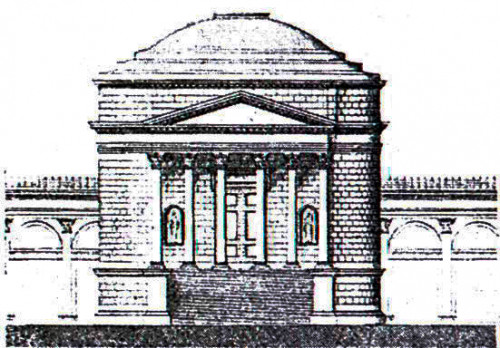

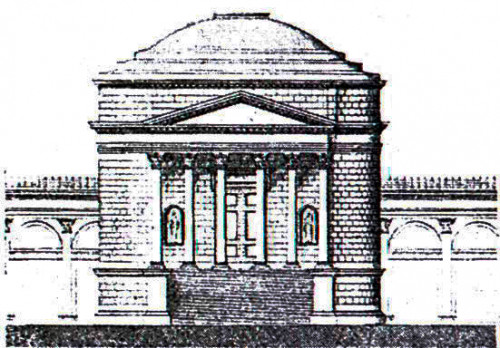

Romulus Mausoleum (Maxentius villa) in ancient times, reconstruction, pic. Wikipedia

Romulus Mausoleum (Maxentius villa) in ancient times, reconstruction, pic. Wikipedia

Romulus Mausoleum (interior) in the complex of Maxentius' villa

Romulus Mausoleum (interior) in the complex of Maxentius' villa on via Appia

Romulus Mausoleum in the complex of Maxentius' villa on via Appia

The Mausoleum of Romulus in the complex of the Maxentius villa, the wall surrounding the mausoleum

Romulus Mausoleum (remains) in the complex of Maxentius' villa

The Mausoleum of Romulus (fragment) in the complex of the Maxentius villa

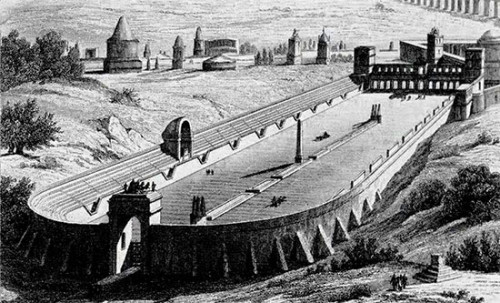

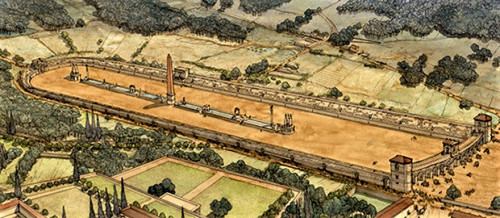

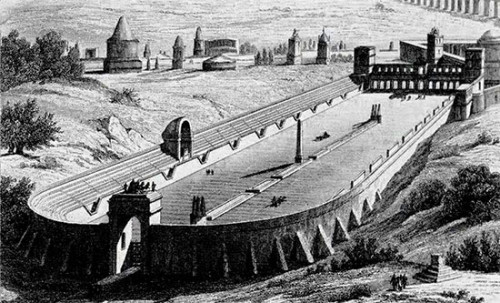

Hippodrome in the complex of the Maxentius villa, reconstruction, pic. Wikipedia

Hippodrome in the Maxentius villa complex on via Appia, reconstruction, pic. Wikipedia

Hippodrome (remains of two towers flanking unpreserved arcades) in the complex of Maxentius' villa on via Appia

Hippodrome (remains of the tower) in the complex of the Maxentius villa on via Appia

The Hippodrome (wall surrounding the running track), the complex of the Maxentius villa on via Appia

Hippodrome (remains of the spina and the main gate - in the background), the complex of the Maxentius villa, via Appia

Hippodrome (running track) in the complex of the Maxentius villa, via Appia

Hippodrome (remains of the wall) in the complex of Maxentius' villa, in the background the tomb of Cecylia Matella

Behind the San Sebastiano gate, merely a few kilometers from the city center, we will find ourselves in an area that is reminiscent of a picturesque countryside. We are at the famous, ancient via Appia – the road which in the past led from Rome to the Brindisi port on the Adriatic. Created out of enormous stone, it still arouses admiration today, despite the fact that the funerary monuments which were located on its sides in the past have (for the most part) succumbed to time. Not far from the Church of San Sebastiano, where car traffic is no longer an issue, there is a meadow with ruins of a well-preserved complex which at the beginning of the IV century served Emperor Maxentius.

Behind the San Sebastiano gate, merely a few kilometers from the city center, we will find ourselves in an area that is reminiscent of a picturesque countryside. We are at the famous, ancient via Appia – the road which in the past led from Rome to the Brindisi port on the Adriatic. Created out of enormous stone, it still arouses admiration today, despite the fact that the funerary monuments which were located on its sides in the past have (for the most part) succumbed to time. Not far from the Church of San Sebastiano, where car traffic is no longer an issue, there is a meadow with ruins of a well-preserved complex which at the beginning of the IV century served Emperor Maxentius.

He did not reside here long, since his reign, which ended with a tragic death in the waters of the Tiber, lasted only six years. But he did a great deal for the city. Not only did he build a great basilica near the Forum Romanum (Basilica Nova), he also ordered the modernization of ancient buildings, aqueducts, city walls, and streets, but above all, he restored Rome as the capital of the Western Empire, a privilege which the city on the Tiber had lost on behalf of Milan. His official residence, as tradition would have it was the palace on Palatine Hill. However, it was here, between the second and third mile of the renovated via Appia, that he decided to build his suburban villa.

Maxentius did not create it anew – a building had existed here since the times of the Roman Republic, picturesquely situated on the slope of the hill, with a view of the Alban Hills. The new host, however, did modernize it and added a hippodrome (a circus) and a mausoleum. Entering the aforementioned meadow and walking through the broad villa, generally alone or sometimes in the company of a few people, since this is not a place which is filled with tourists, we can try to immerse ourselves in the past and imagine the original forms of these arrangements. Despite the fact that we are dealing only with brick ruins, they are well-preserved which allows us to envision the snow-white marble and travertine which used to decorate their external faces.

The remains of the imperial palace, which was in the past surrounded by gardens, are barely visible. From among the three buildings, of which the villa consisted in the IV century, the palace is the worst-preserved. Today we can only see a part of the apse of the palazzo and fragments of the baths. The rest has been lost, although we know that it also included the Temple of Venus and Cupid, as well as the so-called Palatine Aula. During the times of Maxentius, the palace was connected to the hippodrome stands by a portico, which, allowed the emperor to move directly from his rooms onto the stands.

The hippodrome has maintained its shape to a significant degree and is one of the best-preserved ancient structures designated for horse riding competitions; we also know, that it was able to accommodate approximately ten thousand spectators. A walk through the half-kilometer-long racetrack surrounded by a wall is impressive indeed, especially when we begin to imagine the travertine stands surrounding it. Inside there was a spina, whose outline is still well visible – it is around it that chariot races took place. The only element which has been preserved from its former decorations is an obelisk. Its history is quite interesting. In ancient times it was located at the central point of the Temple of Isis on Campo Marzio (The Field of Mars) in Rome. It was then taken from this location by Maxentius and placed in the hippodrome where it survived several centuries until 1651 when it was taken to the Piazza Navona and used by Gian Lorenzo Bernini as a decoration of a fountain that had been erected there (Fontana dei Quattro Fiumi). The rest of the spine was filled with water troughs which served, as may be assumed, not only to quench the thirst of horses but also to freshen up the racetrack which was covered with dust after each race. On one of the shorter sides of the hippodrome, two towers are flanking unpreserved arcades, in which the races started, while on the other side is the arcade of the main, representative entrance. During archeological works few statues of Roman deities were discovered here, which may serve as a testimony to the religious nature of this structure.

After the death of Maxentius in 312 (The Battle of Milvian Bridge) the villa was abandoned. The emperor’s enemy, Constantine wanted to eradicate all traces of his rival, turning over the structure to Christians. In the XVI century, it became the property of the counts Tusculum, and later its ownership was transferred to subsequent Roman families. In 1825 it was purchased by the Torlonia family and then the ground-covered complex gradually began to be excavated. The works were not finished until the sixties of the XX century when it became the property of the city of Rome. Only then was the full body of the round mausoleum uncovered – the third structure which was part of Maxentius’s villa. In the past, a column portico led to it (now this is the location of a utility building constructed by the Colonnas), through which – first climbing a set of high stairs – we can enter inside. The building was created with the son of Maxentius in mind – Valerius Romulus, a youth who had died at the age of fourteen, and whom his father had named after the legendary founder of Rome. The son was to be his successor and take over the role of protector of the city. After the son's death, the father deified him and buried him in this very mausoleum. The structure was reminiscent of the Pantheon in its shape and was an inspiration to many architects of the Renaissance period. In using this form Maxentius showed his love for the ancient architecture of the city on the Tiber. The structure was covered with a dome, under which the room of the cult of Romulus was located (unpreserved), while still further below there were rooms supported by one immense pillar, in which niches were carved out. Similar to those found by the walls, they were to house sarcophaguses – with the body of Romulus and other family members. The area around the mausoleum was surrounded by a wall (still well-preserved today), creating a kind of a courtyard, which was directly adjacent to the via Appia. Separate gates led to the palace and the hippodrome.

We may assume, that it was Maxentius's idea not only to create a leisure complex but also a center of religious and political power, reflecting the young ruler's search for consensus, which had for centuries been the foundation of imperial rule. The cult of the emperor, a return to traditional religious beliefs, and a guarantee of games for the Roman populace were the basis on which Maxentius had wanted to build his politics. His success was to be ensured by a regular supply of grain from Egypt, bread given out in the city, and free games for the Romans to attend. However, the supply of grain was often delayed, which led to revolts, while the hippodrome – as historians believe – had never staged any races, neither in the times of Maxentius nor later. This is further testified to by a lack of sand, which should have filled the circus track.

And that is how the noteworthy political and construction project of Maxentius – ad emperor trying to bring back lost splendor to Rome – ended. His successor Constantine would only appear very sporadically in the city on the Tiber – neglecting both the tradition of the Eternal City, as well as its political significance, which will then be proven by the construction of Constantinople – the imperial city on the Bosporus.