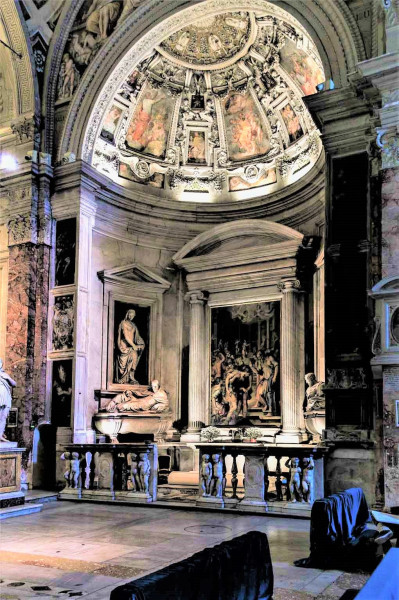

In the pseudotransept of the Church of San Pietro in Montorio, we can come across a chapel which is definitely pleasant to look upon. The harmonious proportions, distinction, and moderation that can be seen there are a testimony of the skill of its creators. Truly, the del Monte Chapel is one of the most beautiful creations of the late Renaissance in the Eternal City, perhaps exactly due to the fact that it was created by the skilled Tuscans who desired to introduce a touch of Florentine elegance into its interior. And apparently, they succeeded.

In the pseudotransept of the Church of San Pietro in Montorio, we can come across a chapel which is definitely pleasant to look upon. The harmonious proportions, distinction, and moderation that can be seen there are a testimony of the skill of its creators. Truly, the del Monte Chapel is one of the most beautiful creations of the late Renaissance in the Eternal City, perhaps exactly due to the fact that it was created by the skilled Tuscans who desired to introduce a touch of Florentine elegance into its interior. And apparently, they succeeded.

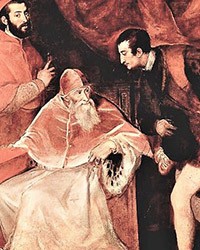

Its designer was the already famous at that time Giorgio Vasari, the author of The Lives of the Most Eminent Painters, Sculptors, and Architects (1550), but above all a Florentine painter and architect who received this commission from the newly-elected Pope Julius III. The pontifex desired to honor his ancestors, but also to create a place which would be a testimony to the grandeur of the family from Monte San Savino in truth a rather modest Tuscan nobility. The ambitious pope wanted to elevate it to the highest pinnacle of the Roman aristocracy and bestow upon it renown comparable to that enjoyed by the Farnese family – an equally unimportant family before the mantle of St. Peter was assumed by its most important representative – the recently deceased Paul III. The chapel, therefore, had to be monumental, but also excellent in style and made out of top-notch materials. It would have been best to entrust its creation to Michelangelo himself, but he was busy with numerous projects and declined, however, he did offer substantive aid. The task fell to Vasari, who was forced to quickly gather his team, but most of all had to find the head sculptor, who would be ready to accept the challenge. His choice was Bartolomeo Ammannati, although some claim it was Michelangelo himself who had made the selection since he was the one in control of Vasari who was his student and greatest enthusiast, which is further testified to by Vasari's The Lives…

Vasari designed a semi-circular chapel, whose center was to be occupied by a painting (completed by him), flanked by two columns, supporting a massive tympanum. The sarcophaguses of the representatives of the del Monte family were placed on the sides. Above them were niches immersed in the wall and adorned with similar tympanums, in which statues of allegories were placed.

Ammannati, who was responsible for creating the principal sculptural elements of the chapel, was unknown in Rome. He was successful in various Italian cities, and in Florence, he completed (1542), the widely commented funerary monument of Mario Nari in the Church of Santissima Annunziata, which brought him both praise as well as problems of a rather delicate nature. On it, he depicted the deceased as a soldier who died during a battle, when in reality he had died in a duel which he himself started, and this was a reason for the widespread criticism.

In the chapel of the Church of San Pietro in Montorio, two significant representatives of the Ciocchi del Monte family were immortalized – the uncle and the grandfather of the pope. The statues of the deceased depict them in semi-lying poses, resting on sarcophaguses opposite each other. The first one (on the left) is Cardinal Antonio Maria Ciocchi del Monte, shown in a thoughtful pose with his head bent low. Above him is the allegory of Religion, to which this influential lawyer at the courts of popes Julius II and Clement VII had dedicated his life. The second statue – of Fabian del Monte (on the right) – seems a bit rawer, but it is also exceptional in execution and perfect in the presentation of the head and hands of the deceased. Above him is the allegory of Justice, since he also occupied himself with law. Both the sculptures show a distinct fascination of their creator with antiquity, but also with the works of the great Michelangelo. They are full of freedom, bereft of unnecessary details, and focused on the characters and emotions of the figures. At the behest of Michelangelo, they were made out of the best white marble brought from Carrara. Ammannati personally went there to find four large blocks and other smaller ones needed to create the balustrade which immediately attracts attention. It is made up of a pair of putti located between colorful marble balusters.

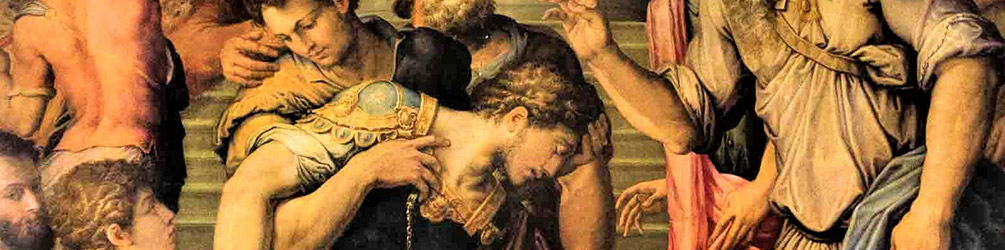

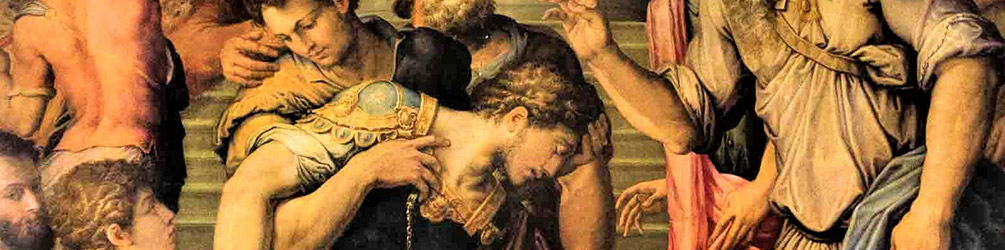

The center part of the chapel is occupied by Vasari’s painting entitled The Conversion of St. Paul. It strikes us not only with the dance-like positioning of the figures especially those moving among the arcades in the background but also interesting iconography.

The painter went against the typical representation of St. Paul during his fall from the horse. Instead, he tells us a story of a repentant Jewish Pharisee, who not long ago persecuted Christians, and who – converted to the new faith – is baptized in Damascus. We can see Vasari himself in the painting on the left – he has a beard, is dressed in black, and looks at us attentively curious of our reaction to his painting, but also to the chapel he had designed.

The sculpting works were completed in 1522, there was still a need to place the painting and finish off the vault of the dome with rich stuccos – emblems with the coat of arms of the del Monte family, festoons, and other decorative elements. Vasari was slightly worried that his work might appear too modest, which most likely was not looked upon favorably in those times, but above all probably would not appeal to the pope himself, who expected splendor and an abundance of wealth. It was Michelangelo who stopped him from using too many decorative elements. The Florentine tradition and moderation triumphed in a lofty and elegant style, that was also restrained. Ammannati undoubtedly referenced his unfortunate Florentine work (the funerary monument of Nari), but he developed it further and gave charisma to his figures. The chapel, in a decisive way, accelerated the development of his career, bringing him to the pinnacle of fame a mere decade later.

The original contract concluded between the pope and Vasari has been preserved. In it, the terms stated that the chapel would be completed in 30 months and it also included the number of sculptures and the materials they would be made out of. A price of 4070 scudos in gold was also specified, which at that time was equal to the value of an urban tenement house. It seems that this was one of the best but probably not the cheapest investment of Pope Julius III.