Interior of the Basilica of Sant'Agostino

The façade of the Basilica of Sant'Agostino

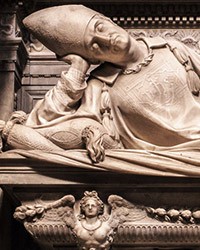

Andrea Sansovino, Madonna and Child with St. Anne, at the top -The Prophet Isaiah, Raphael, fresco, Basilica of Sant’Agostino

The Prophet Ezekiel, Michelangelo, decoration between the windows, Sistine Chapel, pic.Wikipedia

The Prophet Isaiah, Raphael, fresco, Basilica of Sant’Agostino

Giorgio Vasari who is unequaled in helping us understand the art of the XVI century tells us in his Lives…, how in 1512, during the absence of Michelangelo, Donato Bramante acquired the keys to the Sistine Chapel and took his distant relative and colleague from the papal court, Raphael, to see it. The vault of the chapel was nearly finished, however, Michelangelo himself did not allow anybody to look upon it. He protected it against the prying eyes of his colleagues, whom he did not like, and who responded with similar feelings. It should come as no surprise, the closed-off, unsociable, distrustful genius did not share his experiences with other painters, did not take part in their meetings, even though they worked next to him – separated by only a few hundred meters.

Giorgio Vasari who is unequaled in helping us understand the art of the XVI century tells us in his Lives…, how in 1512, during the absence of Michelangelo, Donato Bramante acquired the keys to the Sistine Chapel and took his distant relative and colleague from the papal court, Raphael, to see it. The vault of the chapel was nearly finished, however, Michelangelo himself did not allow anybody to look upon it. He protected it against the prying eyes of his colleagues, whom he did not like, and who responded with similar feelings. It should come as no surprise, the closed-off, unsociable, distrustful genius did not share his experiences with other painters, did not take part in their meetings, even though they worked next to him – separated by only a few hundred meters.

This had to be a significant moment for Raphael. He stood under the frescoes of the vault of the Sistine Chapel and probably was left speechless. He was awestruck by the force and expression of these paintings. He, a painter of ideally beautiful scenes, had to think of himself as irrelevant in the face of such a masterpiece. As Vasari claimed, after seeing the work of Michelangelo, Raphael perfected his own painting and brought it to greatness, providing it with more majesty. Yes, it was probably this majesty that he wanted to achieve. But how to go about it? How to bring it out of his figures? Raphael was an artist formed in a style that was a mixture of that which he learned from his great teachers. From Perugino, he took over the ideally constructed compositions with the exceptionally drawn perspective, from Leonardo da Vinci, this famous "sweetness" of his figures. The work of Michelangelo was yet another inspiration, an artistic challenge, to which Raphael intended to respond, even at the risk of being accused of imitating his colleague. Most likely, he desired to test himself, he wanted to see if he would be able to implement into his works, that which he saw in the chapel, and the opportunity presented itself soon afterward. A well-known Roman erudite Johan Goritz commissioned a small fresco from him for his posthumous chapel in the Basilica Sant'Agostino. It was to supplement the sculpture of Andrea Sansovino. Today those two elements are the only things left from the chapel – the fresco depicting Isiah and the sculpture (Madonna with Child and St. Anne), found in the third pillar, on the left side of the main nave. Both these artifacts were connected with each other – since while the prophet predicted the coming of Christ – the Messiah, the sculpture group found in the niche was to remind all of his human genealogy, at the same time highlighting the role of both the mother and the grandmother of the Savior. On a plaque supported by a putto, we can notice a dedication with the name of the client, while the roll of parchment held by the prophet contains words from his Book: “Open the gates, so a righteous nation may enter, the nation that keeps faith!”

Those who came to the opening of the chapel, the representatives of the Roman literary and artistic elites, which concentrated around Goritz, were faced with a work that was completely different than what Raphael had done previously. Perhaps, some of them noticed the resemblance between his Isaiah and Ezekiel painted by Michelangelo in the Sistine Chapel. There can be no doubts. The same placement of knees, the dynamic twist of the body, and seemingly a wind moving the head covering – the master from Urbino imitated the creator of the Sistine Chapel. Why? Perhaps it was a game, a challenge, or maybe it was out of respect. It must be admitted that his Isaiah seems to be a work of a skilled student of the divine Michelangelo. Only "the sweet" putti supporting a garland are his own, Raphael's – similar to cupids, very different from those of Michelangelo – rather timid and terrified.

As legend would have it, when Michelangelo saw Raphael’s work, he congratulated him on his abilities. This is not impossible, but highly unlikely. Why? Since painting Isaiah, Raphael would often use the “manner” of his famous colleague, which would cause the other to complain. And it seems rather obvious why – most likely he could not deal with the fact, that the most prestigious commissions were obtained by the generally liked youth, who copied his style, while he himself had to be content with second-rate commissions. How did he react to Raphael's fresco? In accordance with the legend, when he was asked a question on what he thought about the high price, which Raphael demanded from the commissioner, he was to respond: “Only the knee is worth its price”, which is clearly ambiguous. We do not know if it is a praise or a criticism of Raphael?

The Prophet Isaiah, Raphael, fresco, 1512, 250 cm ´ 155 cm, Basilica of Sant’Agostino