Antonio Canova’s funerary monument of Pope Clement XIII – death appeased with beauty

Antonio Canova’s funerary monument of Pope Clement XIII, fragment, Basilica of San Pietro in Vaticano

Antonio Canova, funerary monument of Pope Clement XIII, Basilica of San Pietro in Vaticano

Funerary monument of Pope Clement XIII, Antonio Canova, Basilica of San Pietro in Vaticano

Antonio Canova’s funerary monument of Pope Clement XIII, fragment, Basilica of San Pietro in Vaticano

Funerary monument of Pope Clement XIII, fragment, Antonio Canova, Basilica of San Pietro in Vaticano

It was the first work the then twenty-eight-year-old sculptor Antonio Canova completed for the Vatican Basilica. It was commissioned by the nepots of the deceased Pope Clement XIII, who had died in 1769. These proud representatives of an influential Venetian Rezzonico family needed seven years in order to start working to put up a monument for their benefactor and relative. Pasquino himself ridiculed their dilatoriness in numerous satires.

It was the first work the then twenty-eight-year-old sculptor Antonio Canova completed for the Vatican Basilica. It was commissioned by the nepots of the deceased Pope Clement XIII, who had died in 1769. These proud representatives of an influential Venetian Rezzonico family needed seven years in order to start working to put up a monument for their benefactor and relative. Pasquino himself ridiculed their dilatoriness in numerous satires.

We can say that it was worth the wait, since the Venice-born Canova seemed to be the perfect executor. However, he needed another eight years, in order to complete the task entrusted to him. It was by no means easy, not only because the artist was working on the funerary monument of Pope Clement XIV at the same time, in the Basilica of Santi XII Apostoli. The challenge, which he faced was significant indeed, the pressure enormous. He had to confront himself with the masters of great caliber – those whose works were located in every corner of the most important churches of the Christian world. Therefore, he wanted to create something that would surpass them, or at least equal them. It is enough to understand that, across from the planned monument, on the other side of the basilica, there is the outstanding funerary monument of Pope Alexander VII completed by the ingenious Gian Lorenzo Bernini, not to mention the greatest accomplishment of funerary art, the funerary monument of Pope Urban VIII completed by the same sculptor.

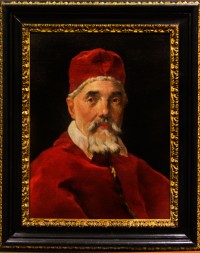

In the multi-colored space of the basilica Canova selected attractive snow-white Carrara marble for his figures and travertine for the lions enriching the monument. The whole composition uses the typical for Vatican funerary monuments (of the Baroque period) structure of a pyramid, divided into three zones. On the bottom, on a high plinth flanking the door we see an allegory of Faith with a cross in her hand. On the opposite side, the nostalgic, winged Genius of Death with a handsome body of a young man leans against a nearly extinguished torch. Both the figures are accompanied by lions lying at their feet. In order to become more familiar with their appearance, the artist went all the way to Naples, where in the local royal zoo he was able to observe their anatomy. One of them (on the side of Faith) looks at us warily, the other seems to be sleeping. The central part of the composition is occupied by a sarcophagus decorated with allegories completed in a relief – Mercy (on the left) and Hope (on the right). The inscription visible in the middle reminds us of the founders of the monument. And finally at the top there is the kneeling, deep in prayer pope with a tiara at his side – an excellent, unfortunately badly visible masterpiece of portrait art.

The allegories accompanying the pope only in a very distant manner reflect his own character, as was the practice on funerary monuments until that time. Clement XIII did not have an easy pontificate. He was a conservative, fervently defended the Jesuits who were being attacked in Europe, in this way facing political animosities, he fought against the Enlightenment, placing among others Diderot’s and d’Alembert’s Encyclopédie on the list of forbidden books. What did then the artist want to impart, choosing such a set of form and text?

In order to understand this we must transport ourselves to the second half of the XVIII century, when once again artists were inspired by classical works and the works of Greco-Roman artists. Showing off Baroque images of death in the form of skeletons holding an hourglass was definitely passé, similarly to the multi-colored marbles, vibrating movement and a strong expression of the presented figures. Peace, harmony and tranquility – these were the elements accentuated and presented by Canova. On the other hand the message of the monument itself refers to not so much the pope, but the human condition at the moment of his confrontation with death. It is then that true faith can aid us – both in the posthumous journey of the deceased, as well as in the suppression of grief and pain of the mourners, this is what Canova seems to be telling us. The sensual and sublime, Apollonian in its beauty Genius of Death makes us become accustomed with the slow, harmonious departure, similar to that which we experience falling asleep. The author, in this way, eliminates fear of death, if that was not enough – he shows us its beauty. It is also worth adding, that this Genius, combining in itself the depiction of death and dreaming, initially was completely nude and in the XIX century it made such a strong negative impression on the eyes and the senses of the faithful that stucco was used to cover his genitals.

In the creation making up the posthumous monument of Clement XIII a certain hesitation is noticeable, some disharmony, a crack. On one hand the dignified and strict allegory of Faith, on the other – the falling, fainting genius. As was noticed by one historian, it is a wonder that he has not yet completely fallen to the floor. In the work, the strength of Faith was accentuated and at the same time the weakness of the Genius of Death – most likely an intended effect, but difficult to express in a composition. Perhaps, the artist himself was well aware of it, since despite words of admiration, which were directed towards him after the monument was unveiled in 1792, he was not quite convinced of its value and reportedly (as an anecdote would have it), covering his face, he mingled with a crowd of onlookers wanting to see the monument. It was not until he had heard praise of his creation that he was ultimately convinced of the value of his work.

In my opinion the monument does not strike with its originality, although some consider it exceptional. Nevertheless, the sculptor introduced a new style into the basilica. Many years later it would once again enter its premises, this time presenting expressive in form and uncompromising in its message funerary monument of the Stuarts.