Formosus, Le vite dei pontifici, 1710, Bartolomeo Platina

Pope Stephen VI, Le vite dei pontifici, 1710, Bartolomeo Platina

Pope Sergius III, Le vite dei pontifici, 1710, Bartolomeo Platina

Pope John XII, Le vite dei pontifici, 1710, Bartolomeo Platina

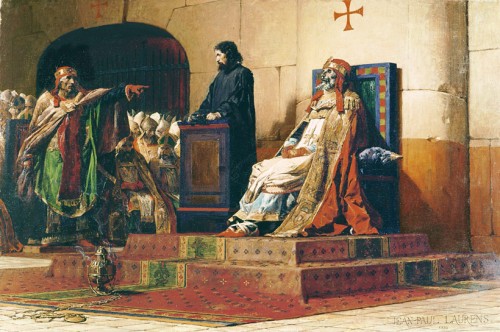

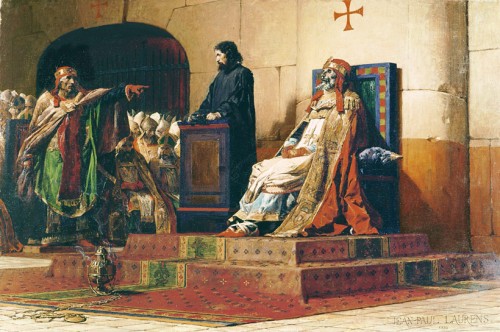

Cadaver Synod, Jean Paul Laurens, 1860, pic. Wikipedia

Pope Formosus, Cavallieri, zdj. Wikipedia

Stories about popes are generally intriguing, often full of surprising content and plot twists, but it seldom happens that the posthumous life of one of them is described more broadly than the earthly one. And I am not speaking of their intellectual achievements or moral values, but of the purely physical aspect, meaning the pilgrimage of the body after death. What I am about to describe is not an invented horror, but a story which has been thoroughly documented.

Stories about popes are generally intriguing, often full of surprising content and plot twists, but it seldom happens that the posthumous life of one of them is described more broadly than the earthly one. And I am not speaking of their intellectual achievements or moral values, but of the purely physical aspect, meaning the pilgrimage of the body after death. What I am about to describe is not an invented horror, but a story which has been thoroughly documented.

Pope Formosus had already been in his tomb for numerous months, when his successor Stephen VI ordered his corpse to be taken out, dressed in papal robes and placed upon St. Peter’s throne, after which the gathered bishops and members of the most important Roman families, for three days listened to the prosecutor (in the shape of Stephen VI himself) and a deacon who filled the role of the deceased pope’s defender. Who was this pope, who was being judged in such a bestial way and what horrible deeds had he committed?

Formosus was probably not bereft of great ambitions and was fully aware of the conflicts among the dukes of the then Italy. He was a Roman, who came to sit upon the papal throne in the year 891. However, before this happened, he had previously attempted to become pope as the bishop of Porto (Latium), not shying away for intrigues and conspiracies. The newly elected at that time pope, John VIII, in order to get rid of the opposition in an efficient way, as well as remove his competitor, did not kill Formosus (which soon became the way to eliminate bothersome rivals), but accused him in 876 of participating in a conspiracy against the pope, removed him from his post and took away his ordination while forcing him to vow never again to attempt to pursue any kind of a church title. When John VIII was poisoned his successor Marinus I, rehabilitated Formosus, while the next pope (Hadrian III) reinstated him as the bishop of Porto. And this is how the bishop could have ended his career, were it not for the fact that at the age of 75 he was finally elected as St. Peter’s successor. Nobody seemed bothered by the fact that this was not in compliance with the then law, according to which, the head of one bishopric was forbidden to change it to another – in this case Roman. This had already happened with Marinus I, whose election introduced a certain novelty. Until then popes were chosen from among deacons (VIII century), in the IX century they were titular clergymen, but this time the new pope was selected by Roman aristocratic families from among the members of the Episcopacy.

Formosus ruled for four and a half years and during that time managed to make numerous enemies. Initially he approved the choice of his predecessor of Duke Guy of Spoleto as king of Italy and emperor. However, after the death of the latter he was unfavorably disposed towards the heir of his titles – the teenage Lambert of Spoleto (Lambert II) as well as his beautiful mother – Ageltrude. He searched for stronger allies for himself and the State of the Church and these he found on the other side of the Alps, in the person of the King of the Eastern Franks, Arnulf of Carinthia. Let us recall that the popes were owners of the lands found in Rome and in its neighborhood, which were only leased from the Church by nobles. They were therefore, very wealthy and played a significant role in politics. Given this situation, the pope dethroned the youth and the legal heir of Guy of Spoleto, then promising the imperial crown to the aforementioned Arnulf – the great grandson of Charlemagne himself. The consequences of this act would be grievous indeed, not only for the pope, but for Italy as a whole, torn apart to an even greater degree by the struggles of rivaling families, which looked with disfavor upon “barbarians” from the North, wanting to bend Rome to their will. It should therefore come as no surprise, that the armies of the dethroned, ex-emperor Lambert occupied Rome, while the pope barricaded himself in the Castle of the Holy Angel, awaiting rescue. When Arnulf came to the Eternal City in February of 896, he threw out Lambert and his mother, freed the pope and then received the promised crown of the Roman Empire. The new emperor had intended to attack the Duchy of Spoleto to put an end to his enemies, however this did not come about. Chroniclers say that he was stricken with paralysis and left Italy. Formosus, left to fend for himself and surrounded by enemies, probably felt tremendous fear, however he died in April – and as was customary – was buried, with all the necessary honors in the Basilica of San Pietro in Vaticano, the same which he had thoroughly restored as pope.

However, his death did not put an end to conflicts between the two bitter rivals. As can be expected Lambert once again entered Rome, accompanied by his mother and with their support, the bitter enemy of Formosus – the aforementioned Stephen VI – became pope. It was then, at the beginning of January 895, when the macabre trial of the deceased took place, which would be remembered in history as the Cadaver Synod. It ended with the announcement of the guilt of Formosus, which was based on the unlawful ascension to the papal throne. Then the deceased had three of his fingers cut off, with which – as pope – he gave out blessings, he was also stripped of his robes, pulled through the Roman cobblestones, to then be unceremoniously thrown into a grave for the poor. However after three days, his corpse was taken out and thrown into the Tiber. All the decrees and resolutions of Formosus were repealed and all his ordinations revoked – which was in fact one of the principal reasons of starting this shameful trial.

However, that is not the end of this tragic pope’s life after life. In the summer of the very same year the dome of the Lateran Basilica (San Giovanni in Laterano) collapsed. Seeing that as a sign of God, the supporters of the deceased Formosus, meaning the presently removed from posts and bereft of ordinations enemies of Stephen VI led to a revolt in the city. The pope was imprisoned and then strangled to death. Still during that year, the following successor to St. Peter, Theodore II, ordered the body of Formosus to be fished out of the Tiber (?) and once again placed in the Vatican Basilica. Full rehabilitation followed a year later, at the initiative of subsequent bishop of Rome (John IX). Seventy-four bishops gathered in Ravenna, rejected the accusations brought against him, and interestingly enough these talks were also attended by the ex-emperor Lambert of Spoleto – next to Stephen VI, the most bitter enemy of Formosus. Rome and Italy were at that time divided into two factions, an anti-Formosus one and a pro-Formosus one.

Several years later Rome was witness to another unveiling of this macabre and grotesque story, showing just how vicious was the conflict that divided the then wealthy and clergy gathered around the pope. This is the only way we can explain the deed of another pope, Sergius III, who ascended to St. Peter’s throne in 904. He was part of the anti-Formosus faction and one of the first of his decrees was another opening of the tomb of Formosus, removal of his corpse and another desecration of the remains this time by cutting off the hand and – once again – throwing the body into the Tiber.

A few years had passed – Sergius died, while a simple fisherman told of an unusual discovery. In his fishing nets he found the remains of Formosus. Once again, for the third time, they were placed in a Vatican tomb, but this time once again fate proved unfavorable. During works on the new St. Peter’s Basilica, all traces of the tomb were lost and it would be in vain to search for it in the Vatican Grottoes as well. The story of Formosus survived as an example of one of the most confusing, yet conducted within the confines of the law, trials in the world.