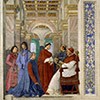

Pope Sixtus IV appointing Bartolomeo Platina as Prefect of the Vatican Library, Melozzo da Forlì, Pinacoteca Vaticana

Bartolomeo Platina, fragment of the fresco Sixtus IV Appointing Bartolomeo Platina as Prefect of the Vatican Library Library

Pope Sixtus IV appointing Bartolomeo Platina as Prefect of the Vatican Library, Melozzo da Forlì, Pinacoteca Vaticana, pic. Wikipedia

His image is well known – it was painted by Melozzo da Forlì on a fresco destined for the Vatican Library. Platina, kneeling in front of Pope Sixtus IV receives evidence of granting him the title of the prefect of this very library, but not only. His finger is pointing to an inscription, on which the deeds of the pope are praised. Who was this independent humanist, professor of rhetoric, who looks like a papal courtier on this painting?

His image is well known – it was painted by Melozzo da Forlì on a fresco destined for the Vatican Library. Platina, kneeling in front of Pope Sixtus IV receives evidence of granting him the title of the prefect of this very library, but not only. His finger is pointing to an inscription, on which the deeds of the pope are praised. Who was this independent humanist, professor of rhetoric, who looks like a papal courtier on this painting?

His nickname came from the town of his birth – Piadena, which in ancient times was known as Platina. He was the teacher of the children of Ludovico II Gonzaga in Mantua, he acquired knowledge in the Florentine Academy established by Marsilio Ficino, then in 1462 along with the court of Cardinal Francesco Gonzaga he came to Rome. Protected by cardinals with philosophical interests such as Jacopo Ammannati-Piccolomini and Bessarion he achieved renown on the then Roman salons and a honorable (bought for 100 florins) lifetime post at the College of the Abbreviators at the court of Pope Pius II. He was a member of the unofficially established by Pomponius Laetus, Roman Academy (Accademia Romana), which brought together enthusiasts of ancient culture. Its members were so fascinated with it, that they even took on Greek or Latin nicknames. With enthusiasm they discussed the ancient roots of the city and strove to maintain its heritage, while at meetings at the home of Pomponius on Quirinal Hill, they read and interpreted Latin texts. These humanists were pleased during the pontificate of an enthusiast of antiquity, Pius II, however, the next pope, Paul II, was not liked by them, especially since in the framework of reform, he decided to do away with, unnecessary in his mind posts, occupied by them in the Papal Chancellery. At the same time rumors spread in the city that – similarly to twenty years prior during the pontificate of Nicholas V – there was an attempt on the pope’s life and an attempt to introduce a Republic in place of the State of the Church, patterned on ancient Rome. When Platina became the leader of the humanists who were released by the pope, demanding the restoration of the posts and at the same time threatening Paul II with a council and intervention of foreign monarchs, the pope ordered the protesters, along with Platina to be imprisoned and shut down the Roman Academy. Imprisoned along with other intellectuals in a cell in the Castle of the Holy Angel, Platina spent four months there (1464/1465) and only thanks to the intervention of cardinals Gonzaga and Bessarion he was freed and reconciled with the pope. And when it all seemed to be going in the right direction, rumors once again spread around Rome about a planned assassination attempt on the pope. Fear gripped not only the bishop of Rome. The alleged leader of the conspirers Filippo Buonaccorsi fled the city and spent the rest of his life as Callimachus in distant Poland, enjoying the recognition and trust of the Polish elites. Platina once again (1468) was thrown into prison, this time with the accusation of conspiracy, heresy and homosexualism. The basis of formulating this last accusation was the fact that he praised the handsomeness of a certain Venetian youth. During a long inquisitorial trial, none of the accusations were proven. Despite that fact, the scientist spend another year in jail and was subject to tortures. And once again thanks to the intercession of the cardinals he was set free, but he was so physically battered, that from that moment on he had a limp. In prison he prepared the first, issued in 1470, cookbook of the Renaissance period.

1471 turned out to be a breakthrough year for Platina. After the death of Paul II, St. Peter’s throne was assumed by – thanks to the votes of positively disposed to humanists cardinals – Sixtus IV. The pope immediately rehabilitated Platina and allowed for the reactivation of the Roman Academy, attaining recognition of the intellectual community. In Platina he obtained a devoted courtier, whom he entrusted with several significant functions and tasks. One of these, perhaps the most important, was the writing down of the lives of the popes (Vitae Pontificum). This is first work systematizing the history of the papacy, Platina began in 1469 and finished ten years later. The work was supported by research but it was not free of purely hypothetical information. He was the one that gave the information, that John VIII was in reality the Popess Joanna. In this chronicle, the author also showed his dislike for his persecutor – Paul II, which for ages impacted the perception of this in truth, quite good pope. For nearly one hundered years, the work was circulated around and was a respected position both among Catholics and Protestants, until 1580 when it was put on a list of prohibited books. Platina was also the official chronicler of the pontificate of Sixtus IV, while in 1475 he became the prefect of the newly arranged and made available to the public library (Biblioteca Apostolica Vaticana). At the moment of its opening it had in its collection 2527 volumes, which constituted of religious texts in Greek and Latin, theological treatises, as well as works regarding cannon law. In an inventory of the collection created in 1481, there were already 3500 volumes, which meant that at the time it was the largest library in Europe.

At that time Platina became a widely respected figure. He died, probably of the plague at the age of 60 and was buried in the Basilica of Santa Maria Maggiore.