Mosaics in the Church of Santa Pudenziana – how the Good Shepherd became a lawgiver

Interior of the Basilica of Santa Pudenziana, apse mosaics

Basilica of Santa Pudenziana, apse mosaics

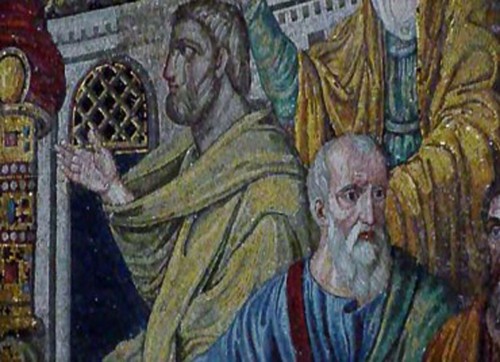

Ecclesia ex gentibus (personification of the Church of pagans) crowning St. Paul, Basilica of Santa Pudenziana

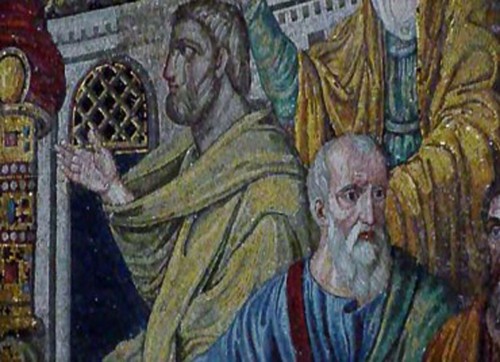

Ecclesia ex circumcisione (personification of the Church of Jews), crowning St. Peter, Basilica of Santa Pudenziana

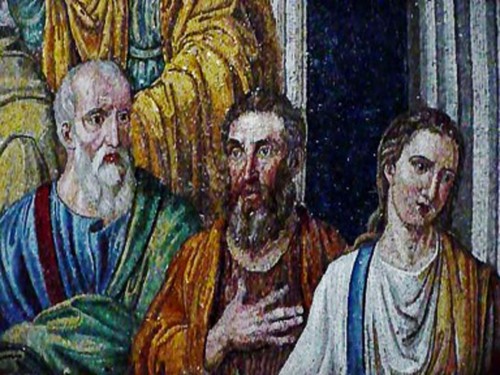

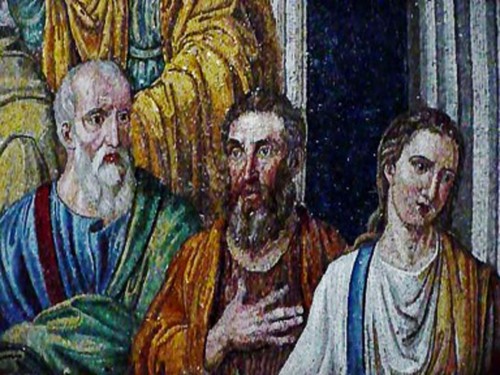

Basilica of Santa Pudenziana, mosaic of the apse, Apostles Surrounding St. Peter – heavily modernized fragment

Basilica of Santa Pudenziana, apse mosaics, fragment

Basilica of Santa Pudenziana, apse mosaics - codex held by Christ

Basilica of Santa Pudenziana, paintings in the dome

Santa Pudenziana, basilica interior

In the year 391 A.D., during the reign of Theodosius the Great, Christianity became the de facto official religion of the empire. The emperor forbade the practice of pagan cults as well as those deemed as heretical. The so-called pagan temples were shut down, while their furnishings either became property of the state or of the Catholic Church. Private offerings to the old gods were also forbidden. Under such circumstances, in one of the old titulae, imposing mosaics were created (402-417), which on one hand seem to be a magnificent example of antique art, and on the other – one of the earliest examples of early-Christian art.

In the year 391 A.D., during the reign of Theodosius the Great, Christianity became the de facto official religion of the empire. The emperor forbade the practice of pagan cults as well as those deemed as heretical. The so-called pagan temples were shut down, while their furnishings either became property of the state or of the Catholic Church. Private offerings to the old gods were also forbidden. Under such circumstances, in one of the old titulae, imposing mosaics were created (402-417), which on one hand seem to be a magnificent example of antique art, and on the other – one of the earliest examples of early-Christian art.

At the beginning of the V century the inhabitants of the Eternal City were still for the most part pagans, closely tied to the old beliefs and classical art, although they were more and more aware of the pressure exerted upon them. Remaining pagan seemed to be doomed to failure. It meant that they were left on the margins of state life and limited their career opportunities. Therefore, it should come as no surprise that, mass conversions took place. Baptisteries scattered throughout the city, were overflowing with people, while the pope could not handle all the baptisms – imperium Romanum evolved into a true imperium Christianum.

It was at that time that Christians began to look for a new glossary of forms and iconography for their art, which until that time had been represented mainly by catacomb paintings and funerary bas-reliefs. Romans, who had for centuries been familiar with the greatest works of Greek and Roman art, looked with contempt upon the primitive Christian artifacts, while for many belief in a man, on top of that a man who was martyred on the cross, was unacceptable. Therefore, monumental art was needed, one that would be convincing, but also one that would correspond to the tastes of the educated Romans and convince them to the new faith. It was perhaps, more appropriate for the Roman audience, to show Christ in Majesty (Maiestas Chrisit), with all the attributes of an authoritarian ruler, more reminiscent of imperial rule, that the spiritual one of a blond-haired youth (the Good Shepherd), sitting on a rock among his lambs and tending his flock.

Let us take a closer look on how this new iconographic motif was dealt with. The apse of the Basilica of Santa Pudenziana, since that is where the aforementioned mosaics are found, is filled with numerous figures of people and animals. Among them are the monumental symbols of the Evangelists – witnesses to the divinity of Christ, who were called to testify with their authority of his greatness. And thus the lion symbolizing Christ the King corresponds to St. Mark, the bull – symbolizing Christ’s priesthood – was connected with St. Luke, the man symbolizing the embodiment of Christ, was identified with St. Matthew, while the eagle – the symbol of the Holy Spirit – was attributed to St. John the Evangelist. The victorious cross stretching out among them (crux gemmata) is reminiscent of the one which was visible on Golgotha in Jerusalem, erected by Emperor Theodosius the Great, as proof of the victory of Christianity over all other religions. In the middle part of the mosaic, Christ is seated on a throne adorned with engraved gems. One hand is raised, in a gesture of an ancient speaker (or in blessing), while the other is supporting an open book, in which the inscription Dominus conservator ecclesiae Pudentianae (Lord and preserver of the church of Pudens), is visible. Behind him, we will see porticos, arcades and galleries of the ancient city, while at his feet a semi-circle of his disciples engaged in a discussion, out of whom the two seated the nearest are elevated by two women, who place wreaths upon their heads. There can be no doubt, that these are the most important Roman martyrs and city patrons – St. Peter and St. Paul. But are these wreaths not reminiscent of pagan ones, which the representatives of Roman provinces, but also Senators used to bring as gifts to their emperor in times of imperial state celebrations, while the saints themselves look like true augusti who co-rule the kingdom of heaven on earth. It also cannot be overlooked that Christ in a gold tunic and an equally gold pallium, seated on crimson cushions, looks like an enthroned emperor, while the apostles in togas are reminiscent of dignified senators or philosophers immersed in a dispute, while the two women – Roman matrons. They are accompanied by ancient architecture, which – just as was the case in the Apocalypse of St. John – with its size and grandeur is a reference to Jerusalem. But, does it not also remind us of ancient Rome, and is it not the Eternal City which is itself the New Jerusalem – the capital and center of Christianity? Ancient structures with a classical glossary of orders and well-known styles were used to appropriately underline the local character of the religion, they were more familiar and convincing than the rather unknown landscapes of Galilea.

However, that is not all, that the mosaic in the apse tells us. The Evangelists presented in the upper part, created thanks to their inspired books, a foundation for the growth of a universalistic religion, combining in it two trends – the Jewish one and the pagan one. The two women handing crowns to Peter and Paul appear in other Roman mosaics, that is why we know that they are – as legend would have it – Pudentiana and Praxes, or the personification of two Churches – ecclesia ex circumcisione, meaning the one which had its roots in Judaism (in circumcision), and ecclesia ex gentibus, having originated from the pagan peoples. Upon closer inspection of both women, we notice that one is old and represents a type of a matron, while the other is young, pretty, with a lock of black hair. Similarly to most figures on the right side of the apse, she changed her visage during latter modernizations. And it is she, as Pudentiana, who aspires to offer her saintly patronage to the church. However, if we once again read the words from the book held by Christ, we will notice, that he calls himself a guardian (protector) of the Church of St. Pudens, recalling the first titulae, which had existed here and was named after the owner of the house – Pudens. A legend which speaks of a merciful martyr Pudentiana, came to be due to a wrong translation of this text.

The mosaic from the Basilica of Santa Pudenziana is the oldest preserved mosaic in a building designated for Eucharist purposes. With is size, quality and a powerful message it by far outshines what we can see in the earlier created Mausoleum of Constantina (Santa Constanza). There the religious theme was delicately incorporated into pagan decorations, here we are dealing with a work of the Church triumphant. Nevertheless, looking at the mosaics in Santa Pudenziana, we still feel, the traditions of ancient art. In them; in the use of chiaroscuro effects and illusionism, in the attention to detail and naturalness of represented figures and their gestures. However, most likely the people from the turn of the IV and V centuries, not only identified with the artistic form of this work but most of all with the message. In order to convince the more and more numerous converts, used to imperial splendor and the everlasting hierarchy, they were shown a new God, in all his majesty – as a protector and the highest power in the empire. Perhaps, such a creation of Christ allowed them to feel more confident in the difficult times of ideological change. The dignified, seated on a globe Christ-Emperor, the proud lawgiver, adored by the apostles-philosophers, who had nothing in common with the Evangelical, illiterate wanderers taken by Christ from one village to the next, in a perfect way corresponded to the image Romans had of a god.

And it is this image of Christ and the apostles, that will from now on always be part of the iconography of Christian art. What a paradox, that Christianity – a religion always fighting against the cult of the emperor – suddenly “dresses itself” in his garments. Centuries would have to pass before the Church “would dare” to replace this image with another – a representation of the crucified body of Christ – a man.

Unfortunately, during subsequent modernizations, in the XVI century, the mosaic in the Church of St. Pudenziana, was not only inappropriately renovated, but also made smaller. Figures of three of the apostles were destroyed (cut off), as was the Lamb – the symbol of Christ’s sacrifice. Yet, it is still one of the greatest examples of early-Christian art in Rome and not seeing it and not immersing ourselves in its aura is a loss that cannot be replaced.